Words: Michael Sharp

Photography: Ashley Mackevicius

Nine-year-old Steve Hogwood was riding his bike home from school in the Suffolk village of Barking one afternoon when he noticed smoke billowing from a building.

“I could also hear these clanging noises,” Steve recalls. “Curiosity got the better of me and I discovered it was the local blacksmith.”

The blacksmith, named Cliff, was “a gruff old guy and I was immediately told to piss off! But I kept stopping off there on my way home, promising to stay out of the way if I could watch. I gradually ingratiated myself with him as he realised I was genuine and he let me do jobs like filling up the slop bucket with water, moving tools and pulling the bellows.

“My mother hated it because I would come home covered in dust and soot, but she let me go because she could see how much I enjoyed it.

“I became fascinated with metalwork. I was just mesmerised by it.”

Steve was born near Aberystwyth in Wales while his parents were on their way home to London from a holiday in the Welsh seaside town of Temby. His father was English, but his maternal grandmother was a proud Welsh woman who wouldn’t speak English to her son-in-law because he was a Saxon outsider. Steve’s mother would have to translate all conversations between her mother and husband from Gaelic to English and vice versa.

“My grandmother was absolutely delighted that I was born in Wales, not the UK,” he laughs.

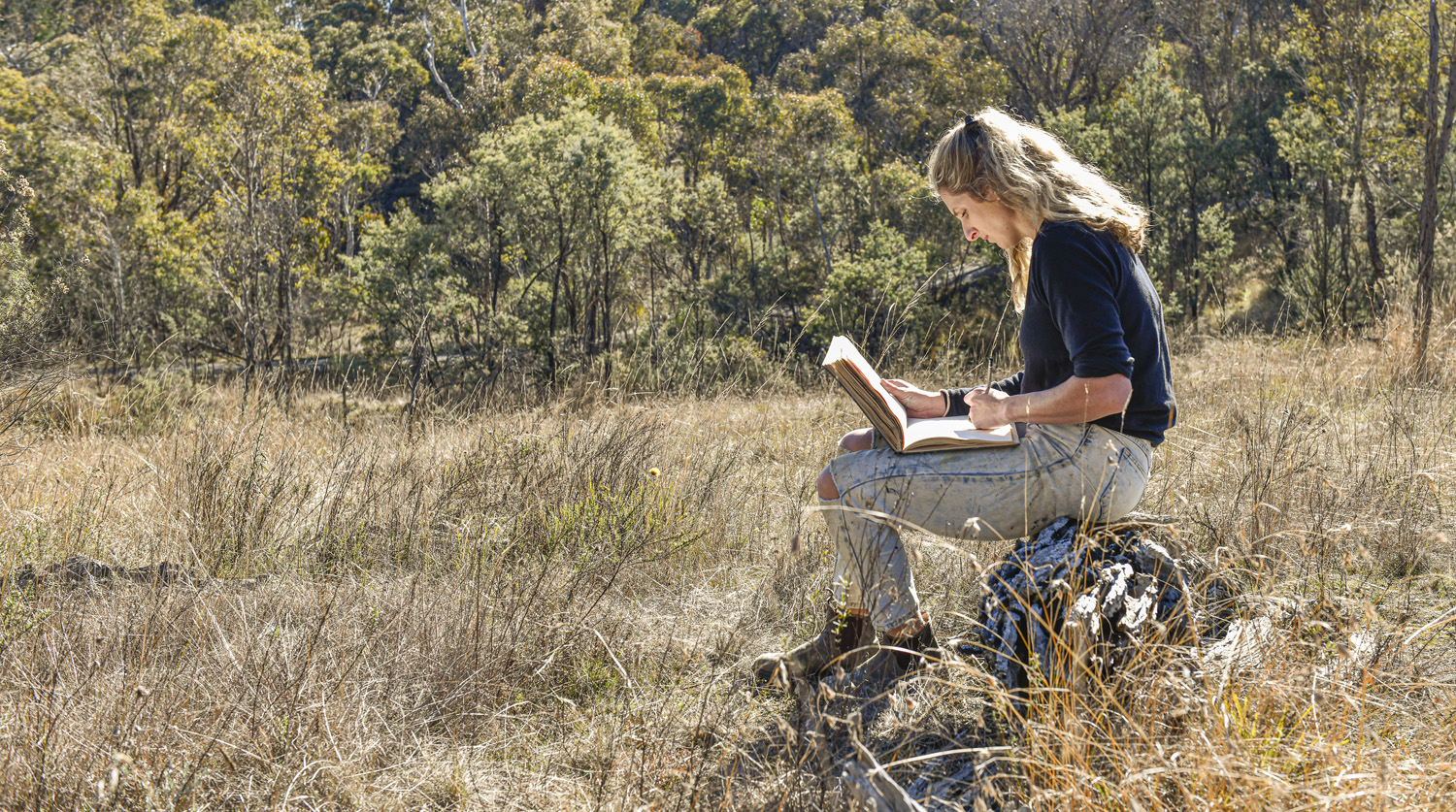

Growing up in and around London, Steve had a love of art from an early age. He was influenced by his first art teacher, the aptly named John Constable, the local vicar who was also a painter as well as the genes on his mother’s side of the family.

“They were descended from Romany Gypsies and my uncle Larry, who worked in the Railways all his life, was a wonderful painter. He loved painting steam trains, which is actually very difficult.”

Steve studied Art for his A-levels and aspired to being an artist, much to the horror of his father who had a background in the Navy and then pharmaceuticals businesses. In 1968 Steve’s father decided the family should emigrate to South Africa and, while the teenage Steve hated the four years he spent there, it provided the opportunity for him to complete a Degree in Fine Arts.

The Hogwood family then emigrated to Australia, spending their first year in the newly opened Endeavour Migrant Hostel in Coogee.

“I got my first job as an ‘ink monkey’ at Southdown Press, which was located down the end of Bathurst Street [in central Sydney]. That taught me a lot about colour and also the production side of the artistic process. However I soon realised I didn’t want to be in printing – I wanted to be on the creative side.”

He managed to find a job as a junior art director at Modern Magazines and began working his way up the art direction ranks, including at Consolidated Press.

In 1974, newly married, Steve moved to The Blue Mountains where he met a local blacksmith named Wyndham Parsons who was “a real character”. They struck up a friendship and Parsons allowed Steve to work with him to develop his amateur blacksmithing skills when the young man had time.

Art direction in publishing led Steve to the advertising industry, where he worked for three decades. This included a senior role at George Patterson where he was involved in numerous major campaigns, including the Sydney Olympics. After George Patterson he ran his own agency and then a consultancy. Through advertising, Steve met and worked with numerous talented people in Australia’s small film industry, including Peter Weir and Chris Noonan. While his official role might be Art Director, Steve’s interest in blacksmithing meant he became involved in making props for both advertisements and film.

In between work contracts, Hogwood would also travel to Parkes to spend time with John Parker, a sixth generation blacksmith, wheelwright and coach builder whom Hogwood met while visiting the Elvis Festival for work.

And so while Hogwood built a successful professional career, he simultaneously pursued his passion for blacksmithing in what today might be called a side hustle.

“It allowed me to foster my love for ironwork and I loved it.”

1910 Ironworks

For the past 20 years, Steve has further developed his blacksmithing skills – and it is now his sole focus. Why did he name the business 1910 Ironworks?

“1910 is the point in history when the modern industrial way of life that we know started,” he explains. “It was the end of the Edwardian period and the end of the age of innocence. It was also the end of the artisan as such. It is when modern life started.”

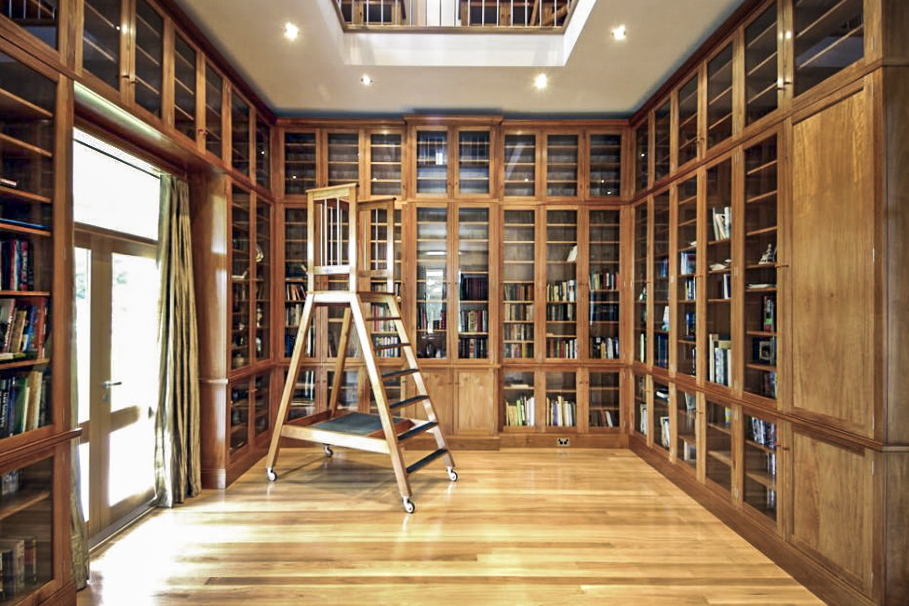

More than 110 years later, old artisan skills survive in small pockets like Steve’s workshop in The Southern Highlands village of Wildes Meadow. His shed is overflowing with rusted tools collected over the decades as well as objects awaiting repair and restoration while enormous bellows, an assortment of anvils and cogs, cuts of metal, wooden carriage wheels, wringers and a range of other metal machines are distributed around the yard.

The company’s motto is: Forging the future while restoring the past.

Steve uses an open coal forge two or three times a week, despite the modern alternative of a gas forge. While a gas forge is very efficient and cleaner, a coal forge has important advantages.

“Blacksmiths today use a coal forge not just because they want to preserve traditional skills, but many say that a coal forge is hotter and more responsive. Also, because a coal forge is open, you can lay steel across it and move the steel around. A gas forge is a bit like a box and more constrained. A coal forge is also better for forge welding, where you take two pieces of white hot steel and join them together by hammering. That is very hard to do with a gas forge.”

A few years ago, 1910 Ironworks experienced a significant increase in demand.

“During COVID, blacksmithing went ballistic with people wanting things like gates and balustrades made. It was very busy and I had two guys working with me full time. After COVID, that work went back to places like China because it is so much cheaper.”

Thankfully, the reduction in that kind of blacksmithing work has been almost replaced by increased demand for restoration and sculptural work.

“In recent years I have been restoring a lot of vintage stoves because they require a real understanding of metalwork and there are a lot of little bits and pieces that need to be made by hand.”

Who wants an old stove restored instead of buying a new one with a vintage look?

“It might be a family heirloom and the family wants to restore it for posterity and to the standard when grandma had it. Or someone has bought the stove at an auction and wants to restore it to use as part of an outside kitchen or barbecue as a feature. And then there are younger people who have bought an old house and discovered an old stove in the kitchen or lounge room. They are interested in the historical significance of the stove and decide to have it restored.”

Most of Steve’s work results from word of mouth and the restoration of a vintage stove can lead to other fascinating challenges.

“I was in Nyngan restoring a magnificent old stove in the pub and a woman asked me about some figures made of spelter [a zinc-lead alloy that ages to resemble bronze]. The figures had been found in a local garden and she wanted to know if they were worth restoring. She sent me some photos, I did some research and discovered they were made by a well-known nineteenth century French artist named Auguste Poitevin. One figure was made in about 1840 and the other in about 1860. I told her they are definitely worth restoring.”

Other current restoration projects include a 1926 Tip Dray, which was pulled by large horses around Goulburn to cart heavy loads such as crushed rock for roads, a 19th century coffee mill and a 16th century Spanish sea chest.

Steve is grateful for the mentoring provided by the blacksmiths who have guided him over the decades, from Cliff in Barking to John Parker in Parkes and Wyndham Parsons in The Blue Mountains. More recently in The Southern Highlands, he spent valuable time with Josef Balog, a seventh generation blacksmith of Polish heritage whose sons founded the Artemis winery in Mittagong, before Josef died in 2017.

Steve is now 70 years old and keen to pass on his skills. He offers one-on-one blacksmithing classes but laments that many students only want to make objects like knives.

“They are not interested in general blacksmithing or decorative work or how to make a beautiful, rolled hinge for a church. Unfortunately, those skills are dying – which is a real shame because I think there are applications for those skills in the modern world.

“General blacksmithing is definitely dying, because there are cheaper options. It’s a horrible thing to say, but it is what it is.

“The saving grace looks to be restoration work and the artistic, sculptural side of things. I hope that continues. I love my work and I think it’s important for future generations.”