This Must Be The Place

- Nicci Bedson

- 9 Oct—9 Nov 2025

- Download now

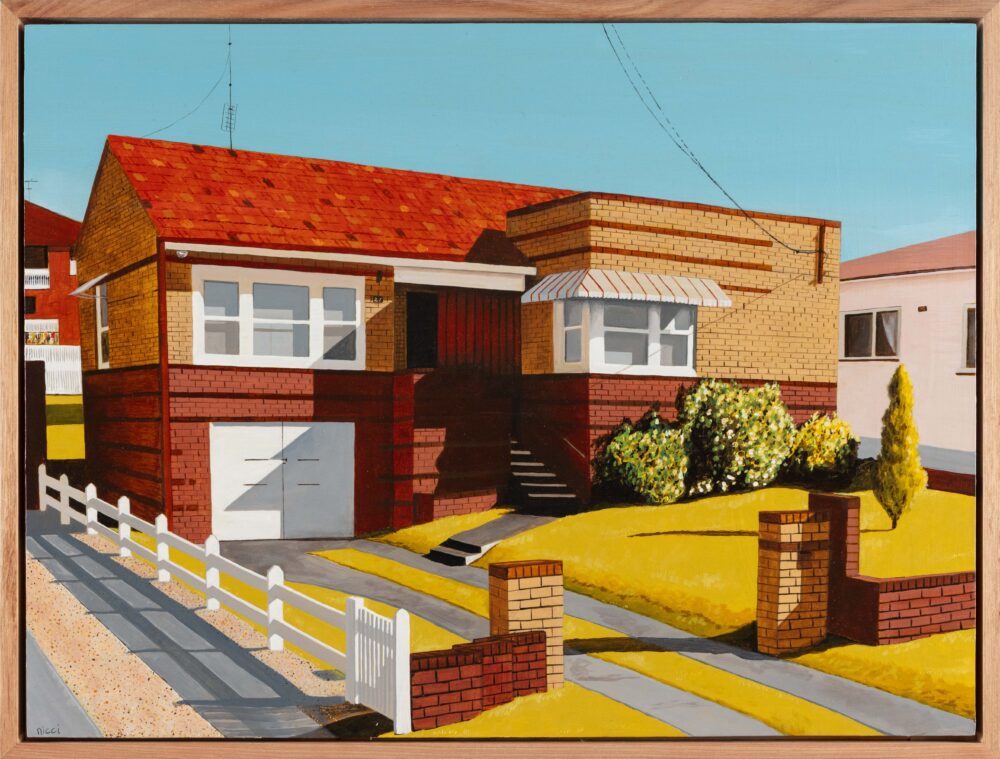

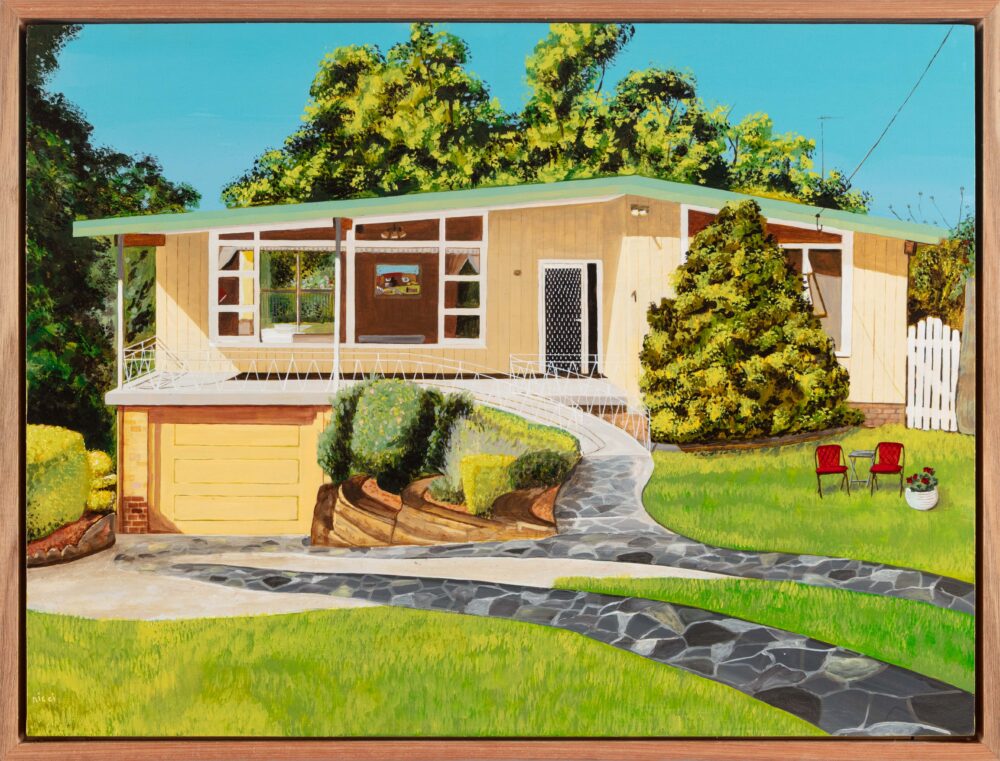

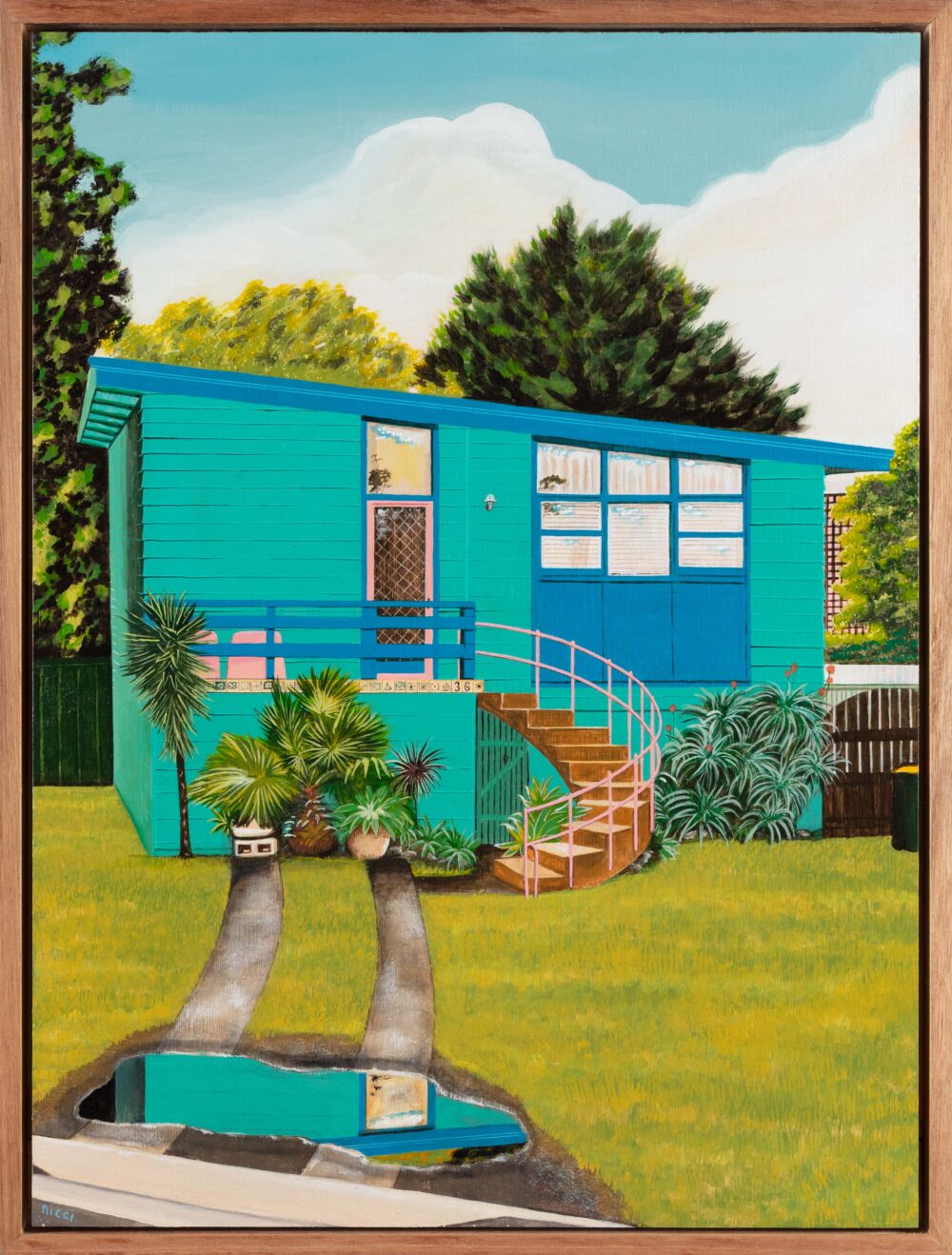

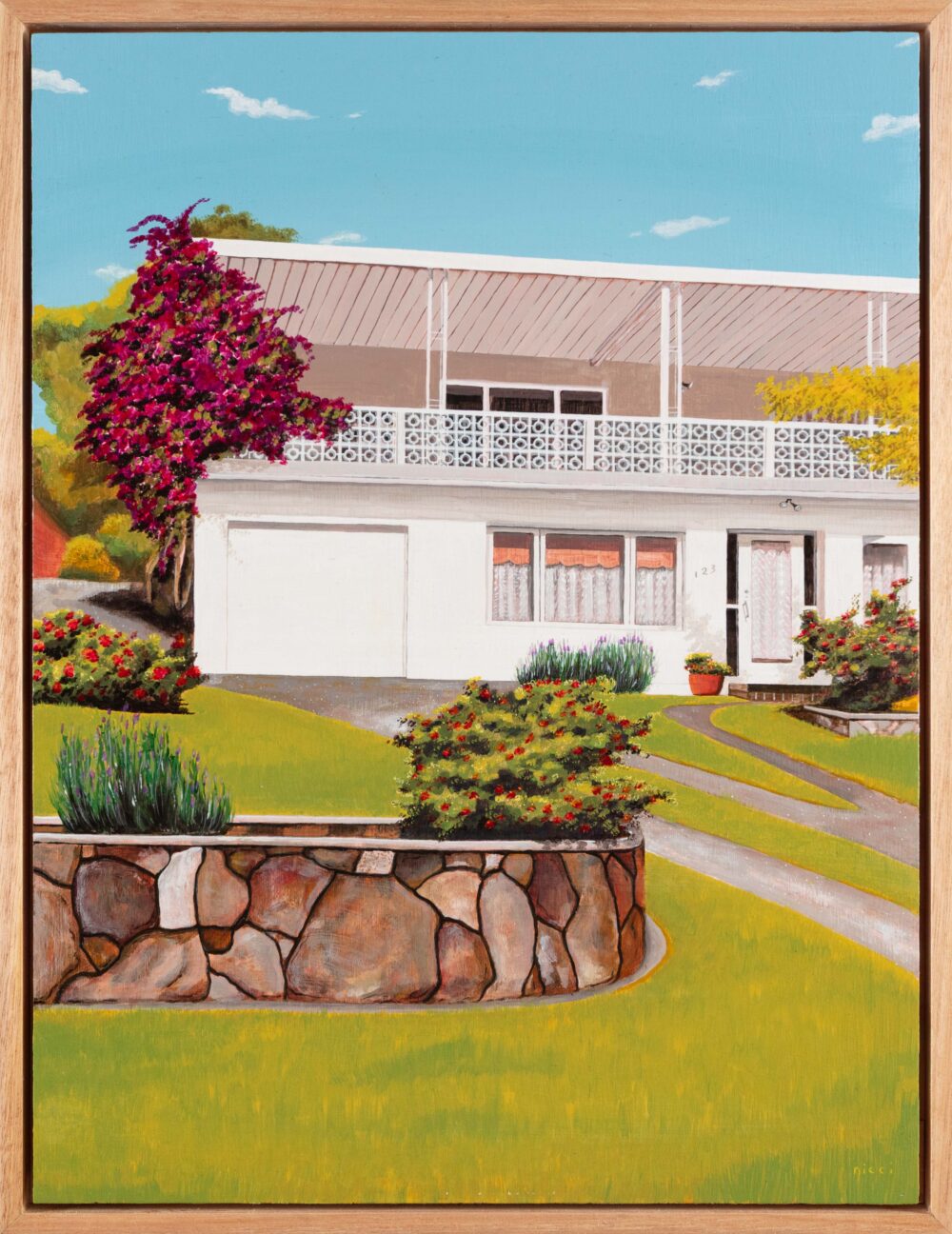

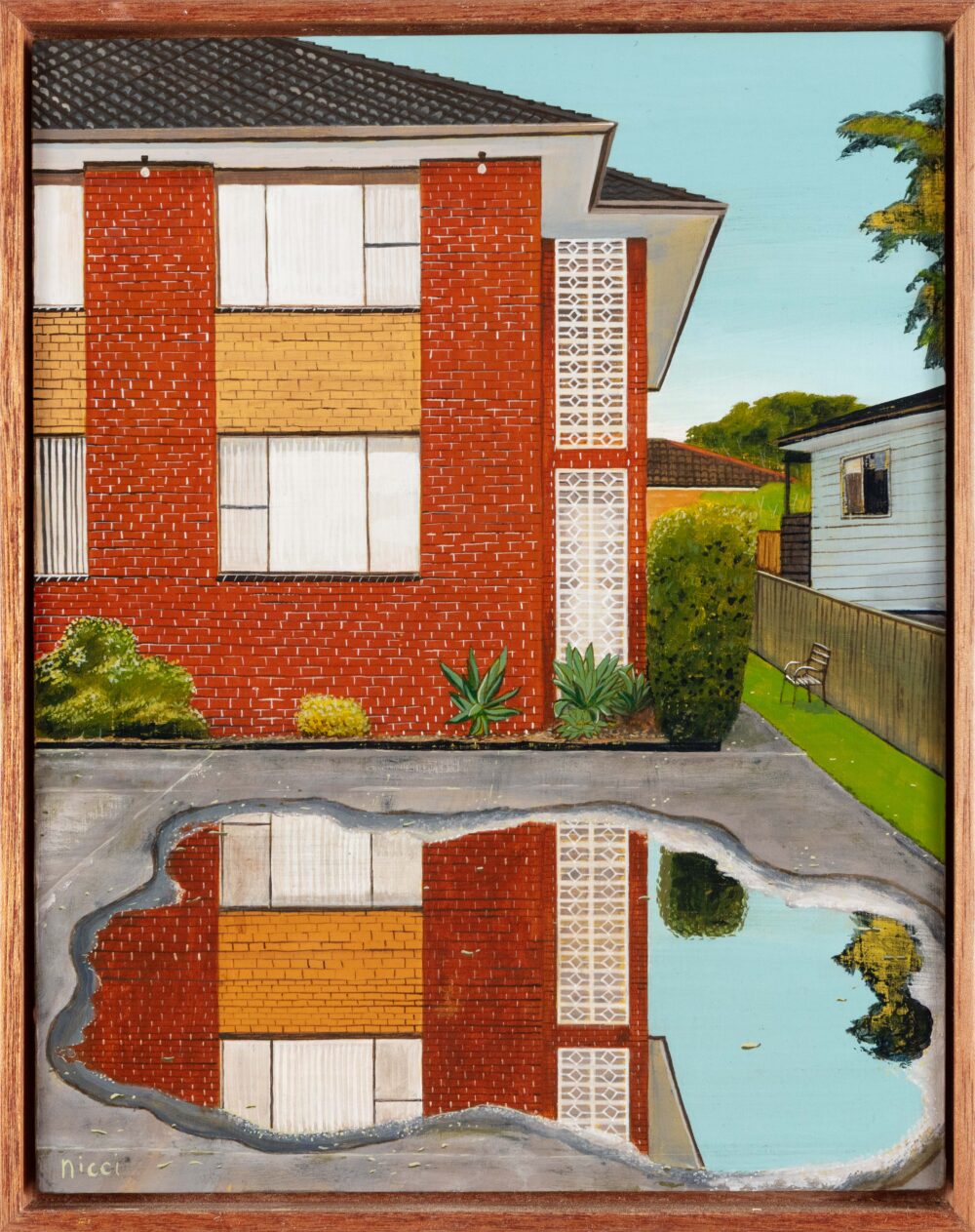

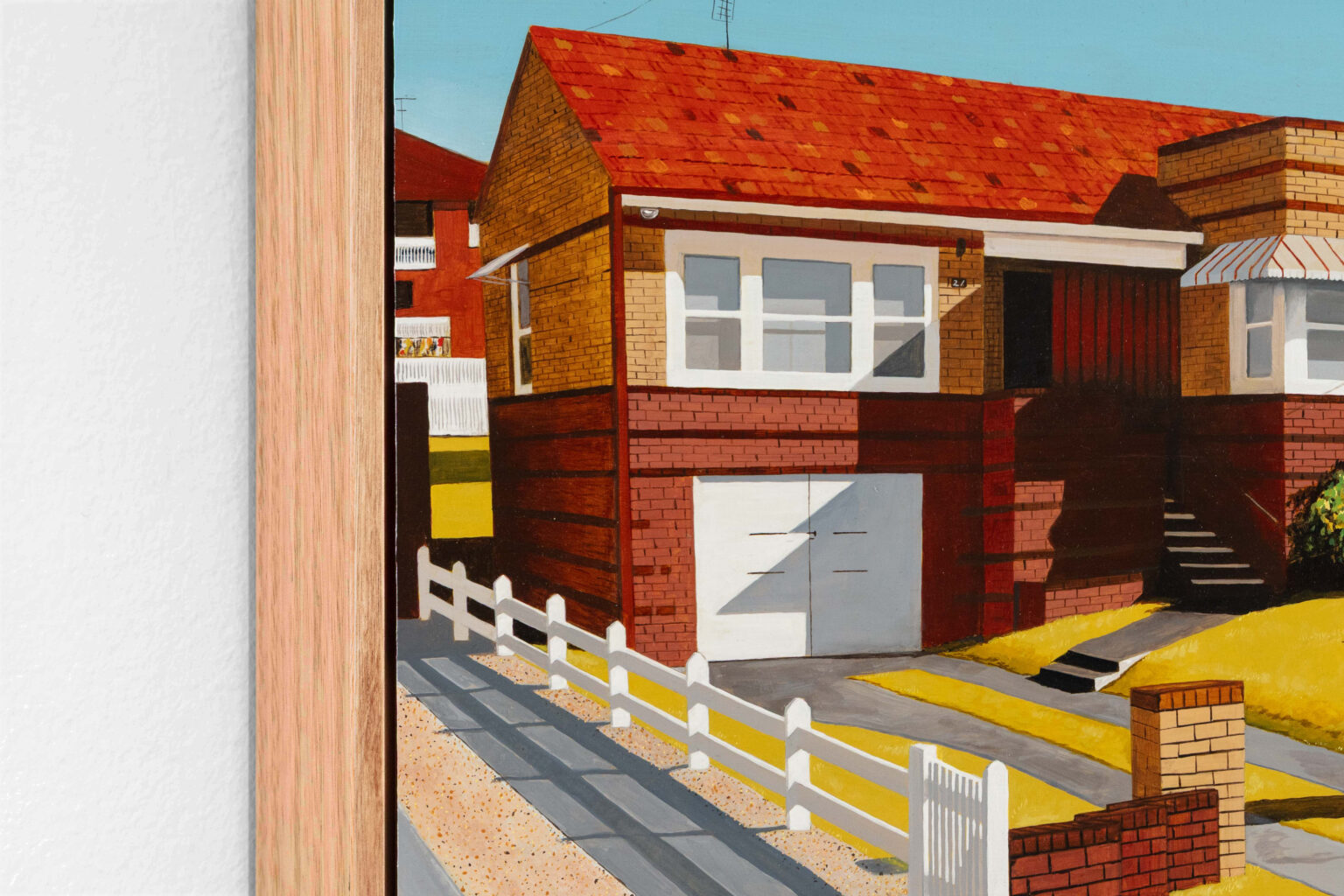

In her debut exhibition with Michael Reid Southern Highlands, Nicci Bedson paints the fibro cottages, brick veneer homes, and weatherboard cottages that defined the Australian suburban and semi-urban landscape after the Second World War. Rendered in meticulous detail, these buildings -once dismissed as ordinary- are given the halo of artistic attention, elevated as the structures that, for decades, cradled Australian lives.

“For me it’s about the house as architecture, as a marker of a certain time and place in history,” Bedson explains, “but also the house as a vessel for all the memories and lives lived inside.”

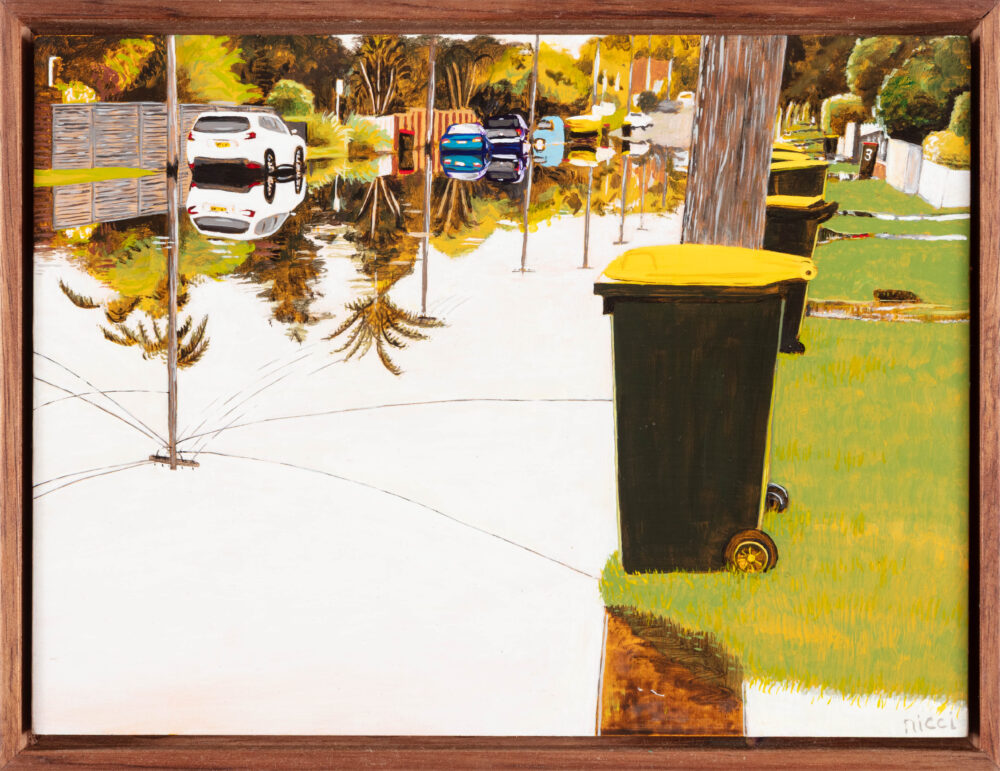

“Often when I am driving or walking around my local suburbs I will catch sight of a scene or house that takes my fancy, purely aesthetically, and I’ll take photos to capture what I can in the moment,” Bedson says. Back in her studio—her sunlit bedroom, adapted for daily work while her young son is at preschool—she translates these glimpses into paintings. Working in acrylics, she begins with an undersketch, builds up the ground, and blocks in colour. From there, details emerge slowly, sometimes over weeks, with the “tiniest of brushes” and even paint pens used to articulate shadows, bricks, roof tiles, or the glint of a sunlit window.

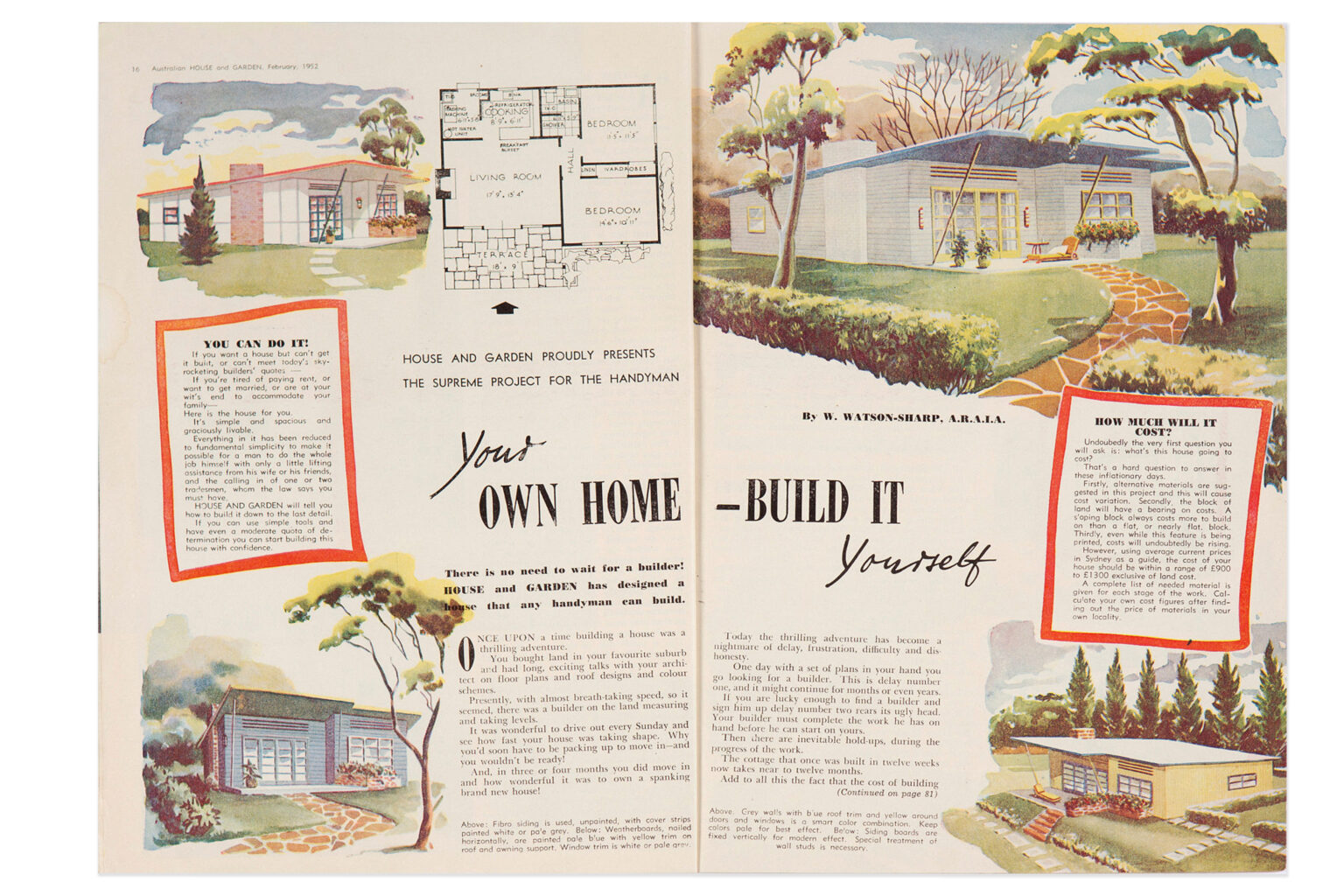

The subjects Bedson depicts so lovingly have their origins in a distinct social and architectural moment. In the immediate postwar years, Australia faced unprecedented demand for housing. Fibro and brick veneer, along with mass-produced fittings and prefabricated elements, allowed for fast and inexpensive construction. Architects, department stores, magazines and newspapers responded with accessible plan services: the Small Homes Service run by the Royal Australian Institute of Architects; Grace Brothers’ advisory bureau, complete with a model home; The Australian Women’s Weekly’s plan booklets. What emerged was a new kind of suburbia—stripped of ornament, box-like and functional.

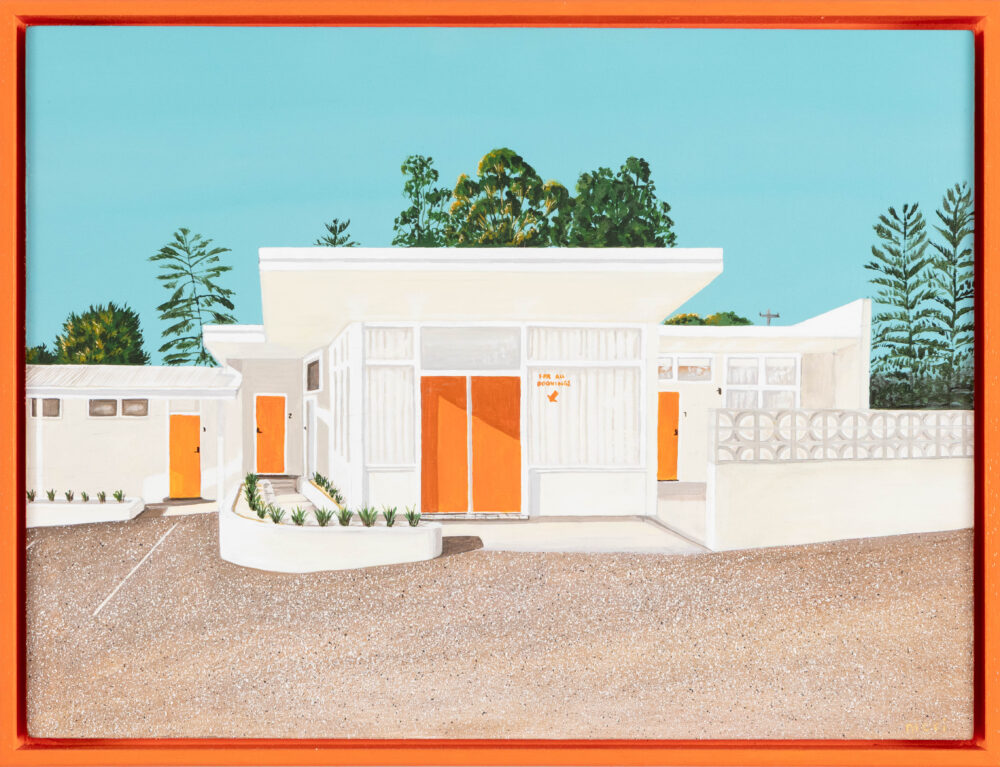

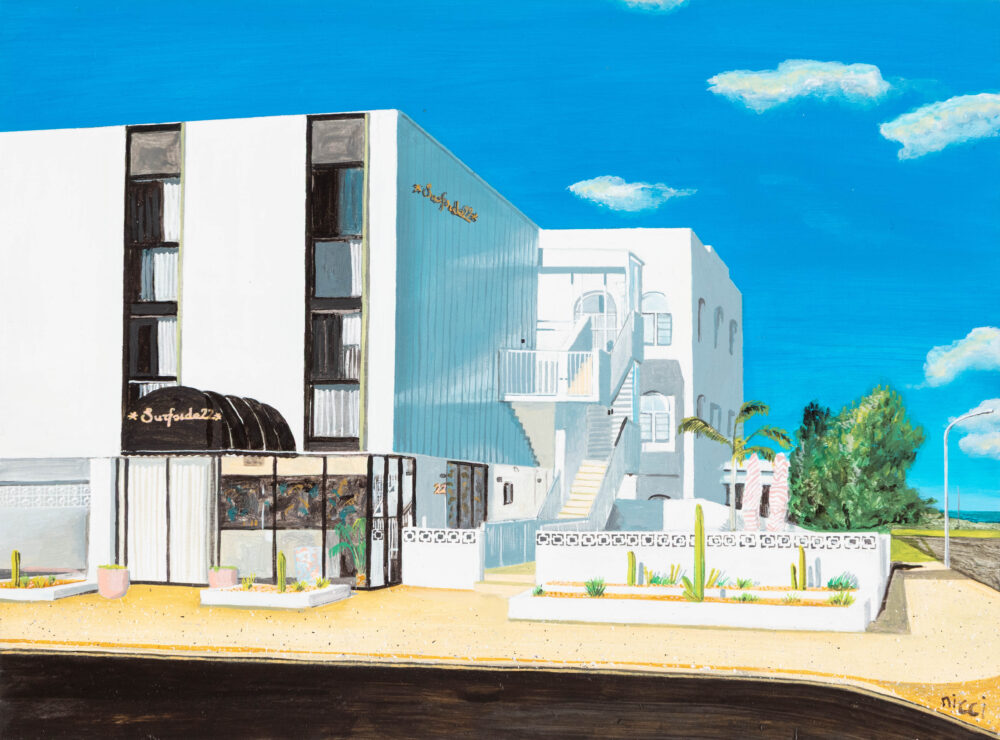

Yet Bedson’s vision stretches further than the humble fibro. Other works in the exhibition turn to the flashier edges of mid-century design—motels, apartments, commercial façades. With their palm-lined courtyards, candy-coloured doors, geometric brick screens and cursive signage, these buildings embody a different postwar dream: one of leisure, travel and aspirational modern living. In sharp contrasts and heightened palettes, what Bedson calls her “vivid realism, where pop art meets traditional style” reveals itself most clearly. These works are celebratory, even theatrical, offering a counterpoint to the restraint of the suburban cottage.

The exhibition’s title—This Must Be the Place—is both a statement and a question. For postwar families, these dwellings were modest sanctuaries from which new lives unfolded, or places of frivolity and escape. For contemporary viewers, the phrase can be heard as longing—for striped awnings, hibiscus hedges, the slap of bare feet on hot asphalt—or as elegy, marking houses already erased in the name of progress. Bedson suggests both readings are true: these homes are simultaneously here and gone, vivid in memory yet vanishing from the physical landscape.