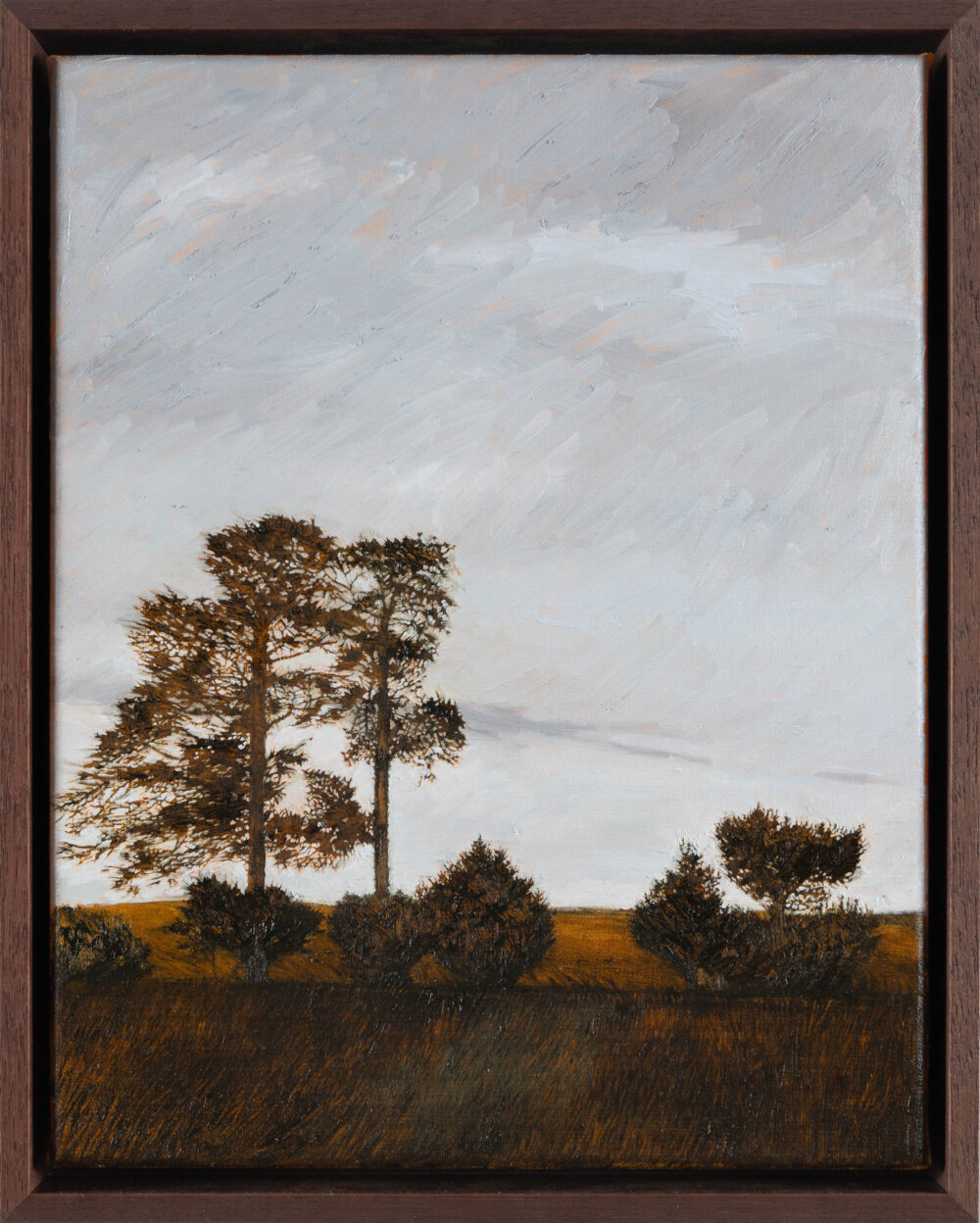

Out of the Blue

- Armelle Swan

- 8—25 Jan 2026

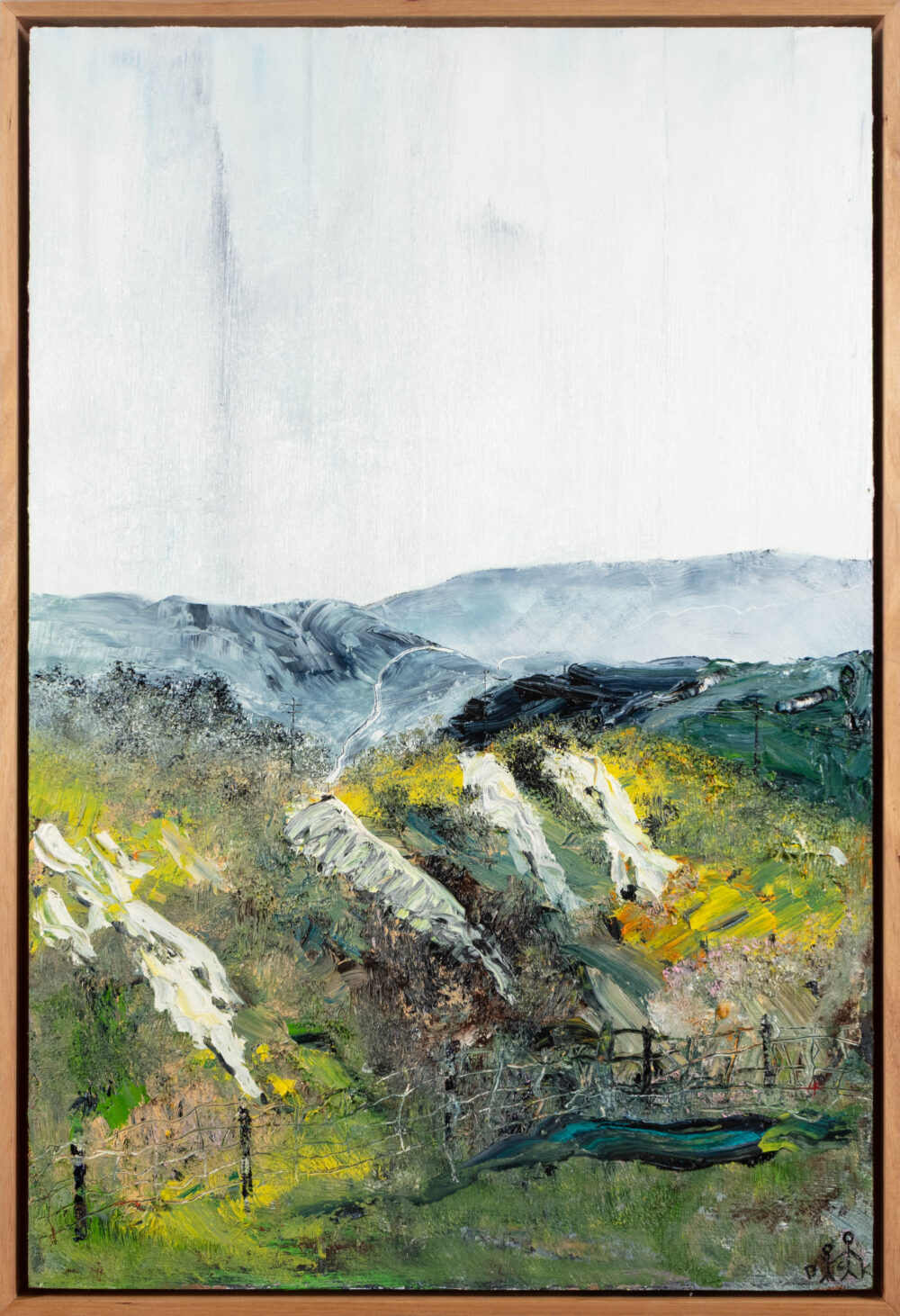

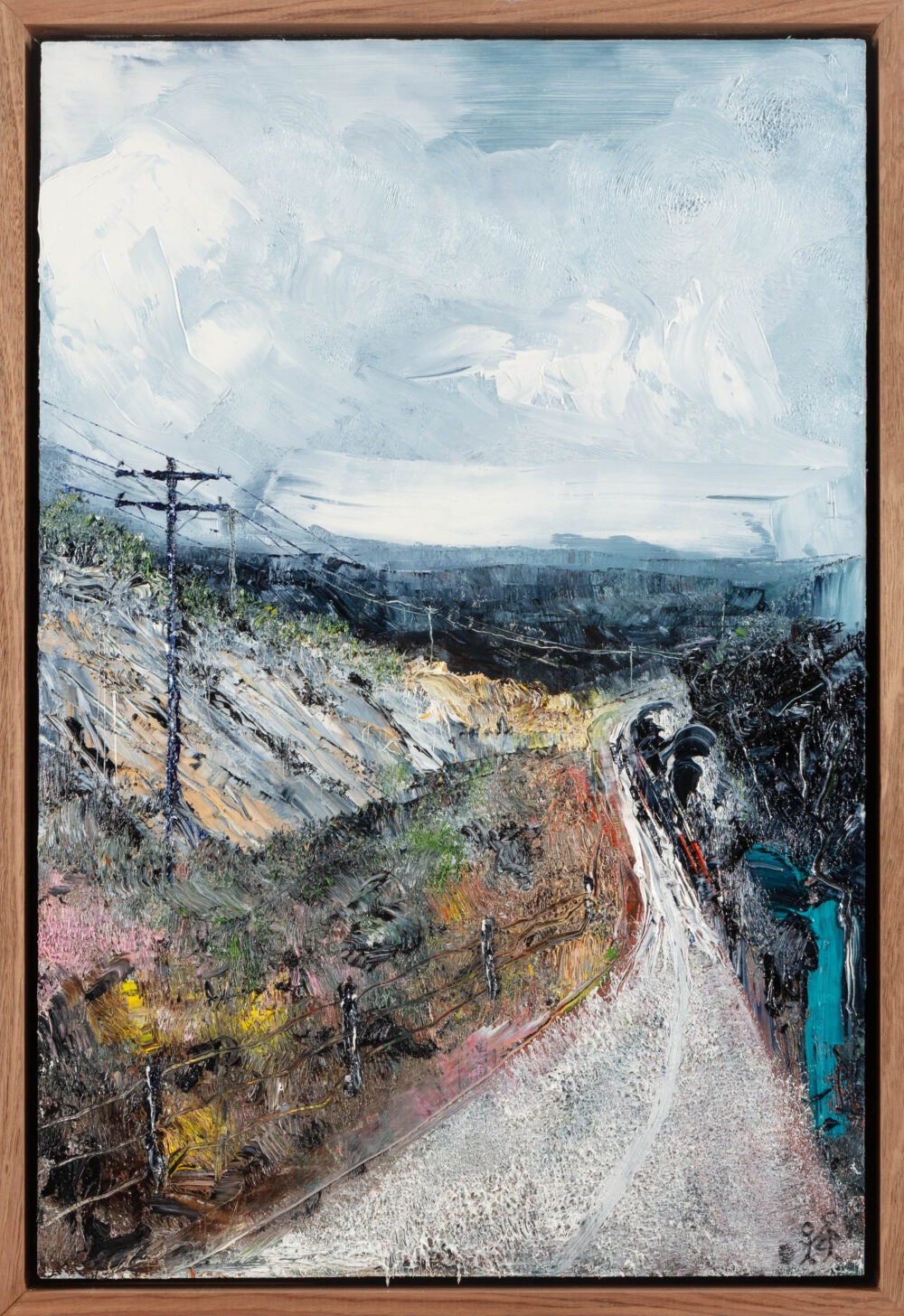

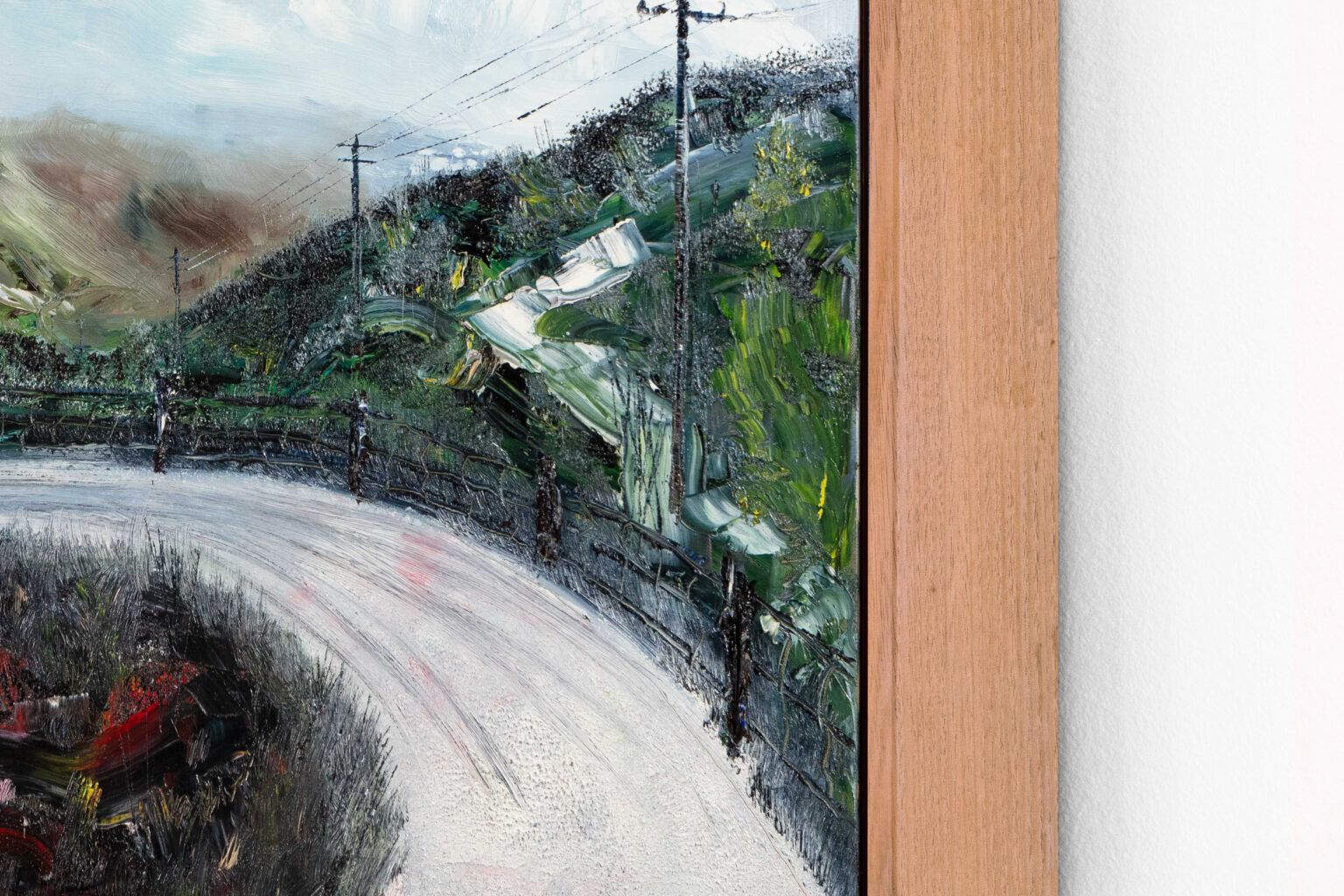

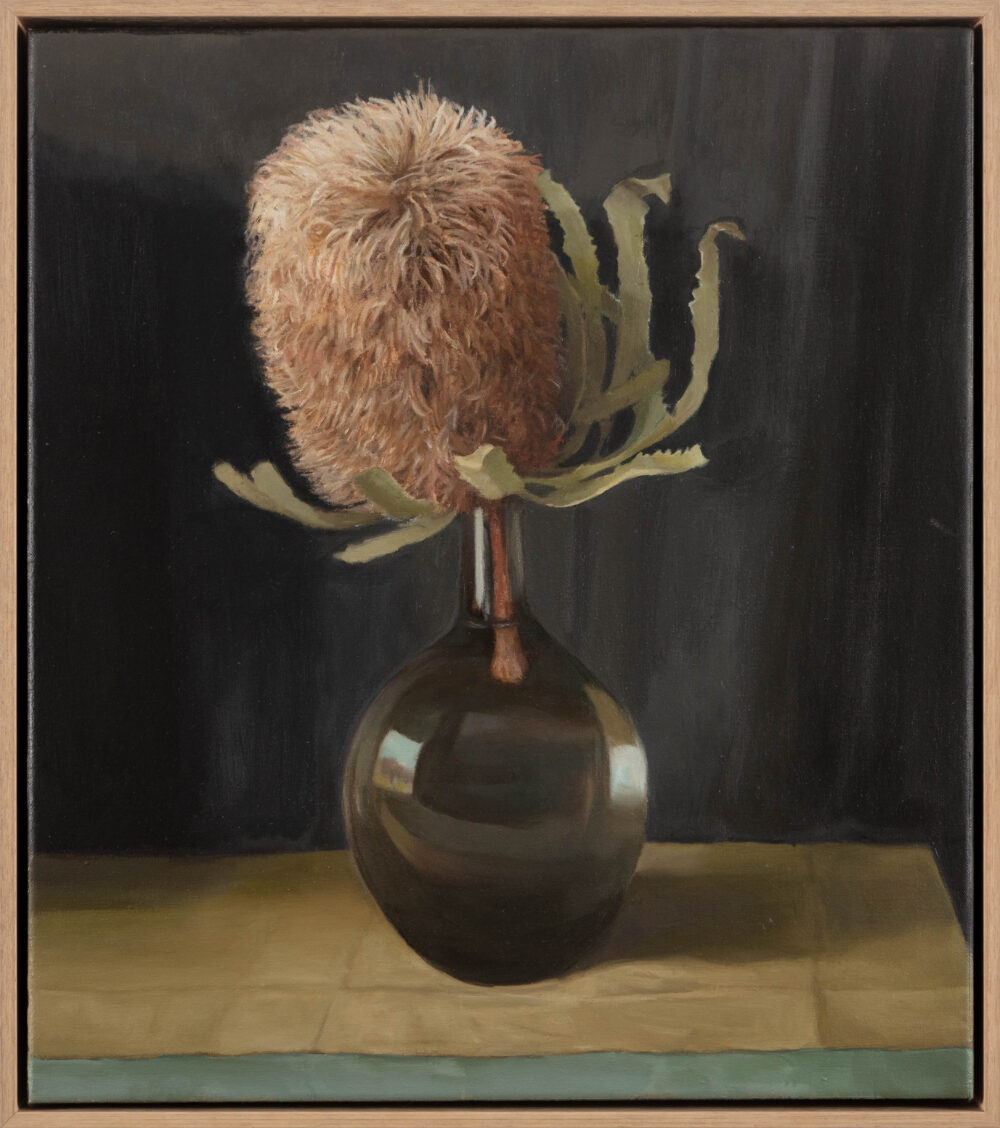

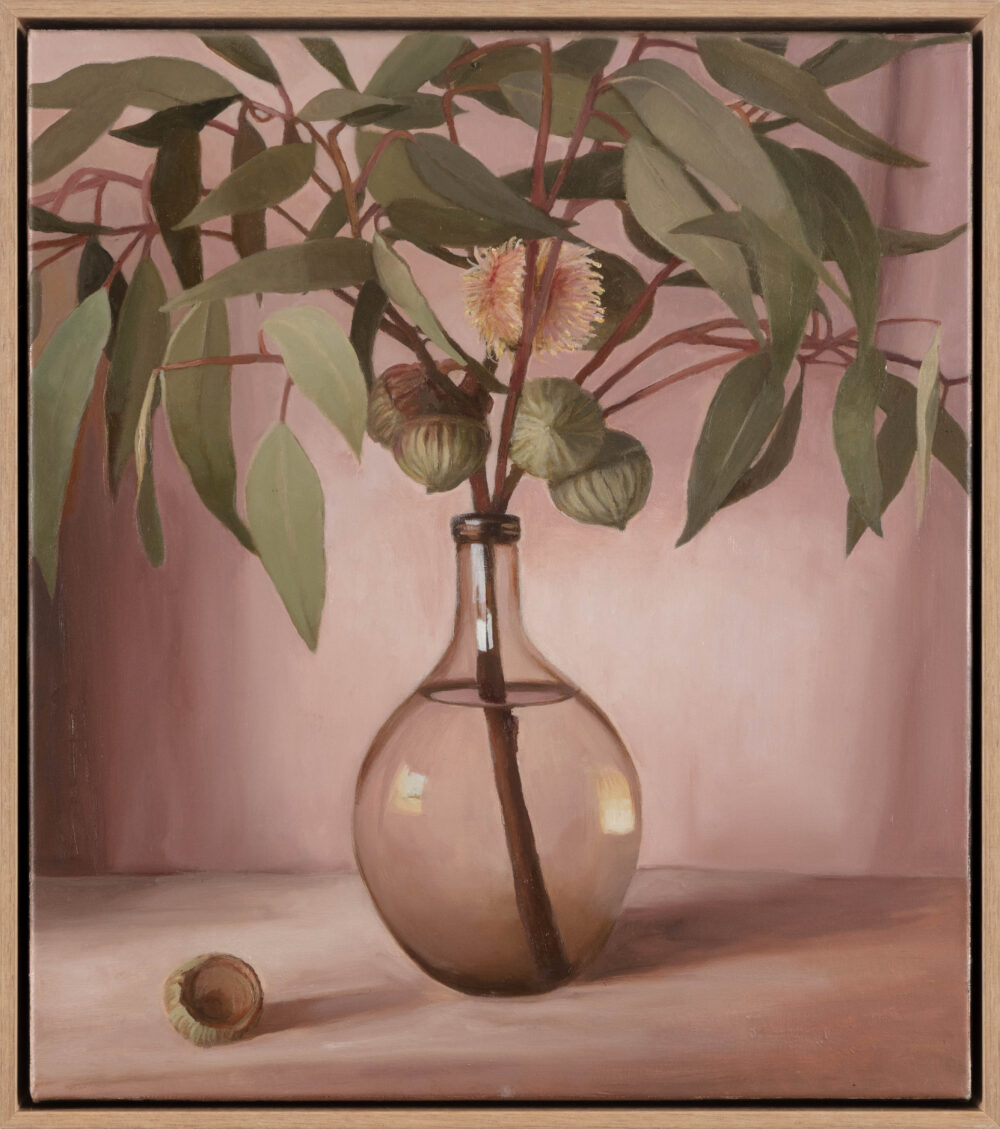

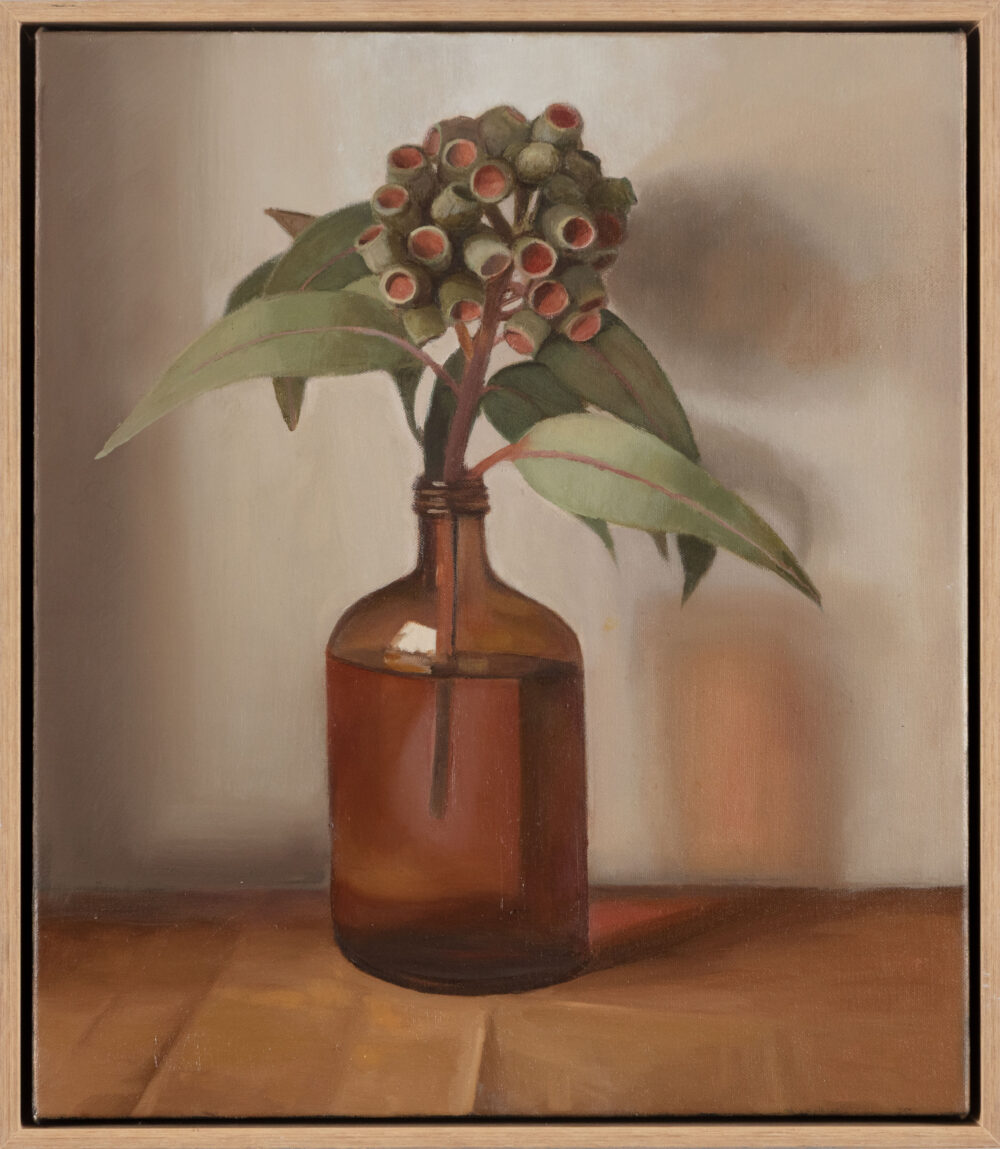

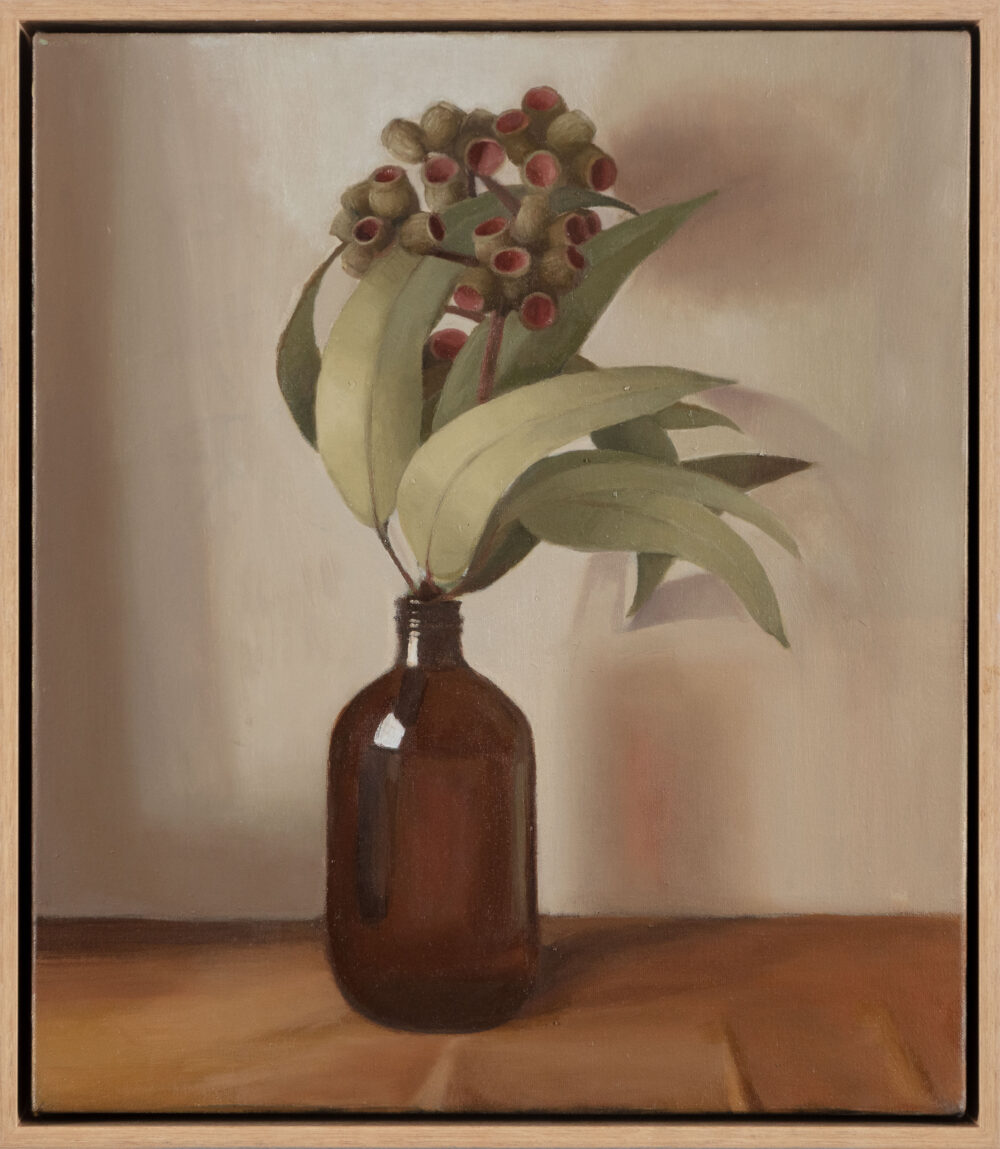

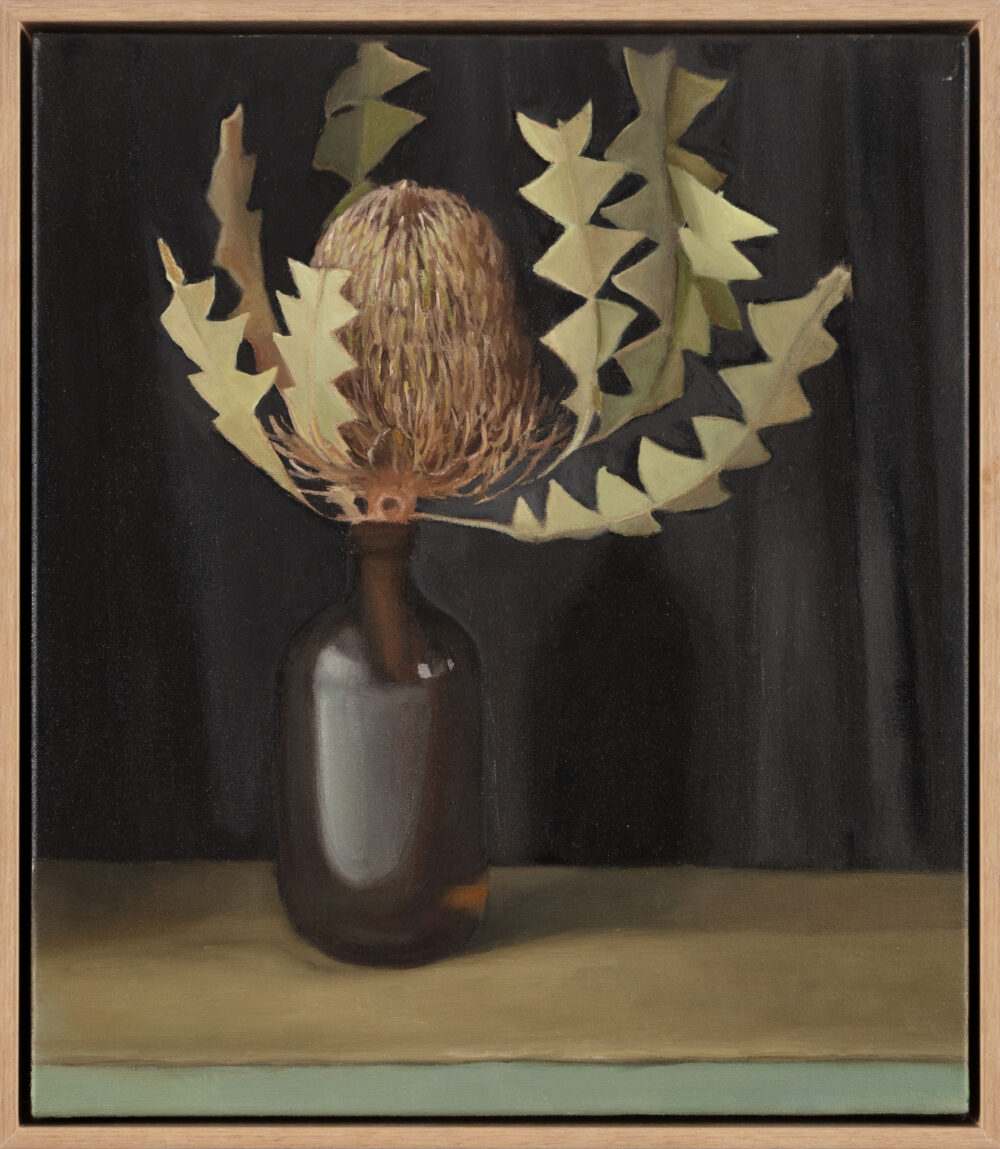

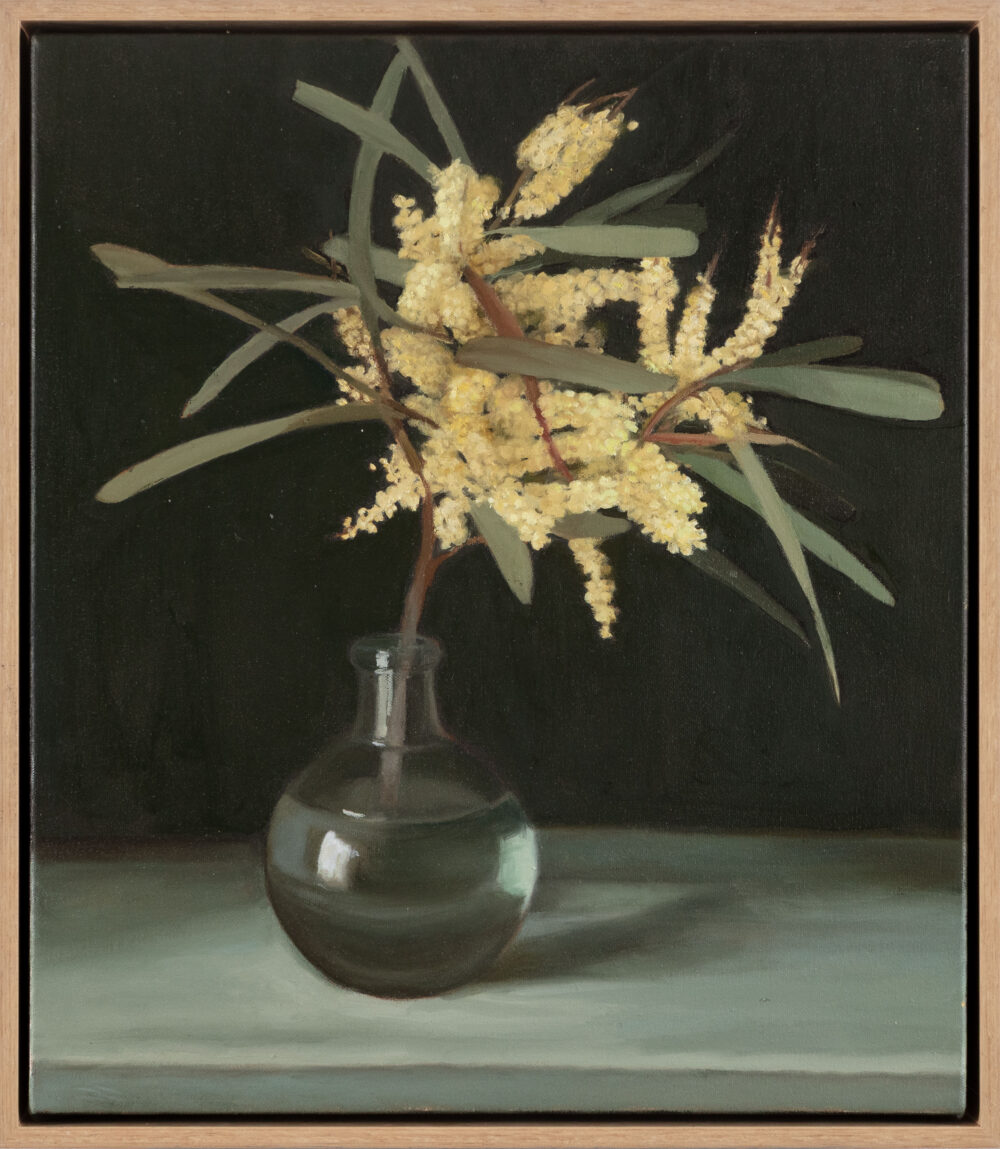

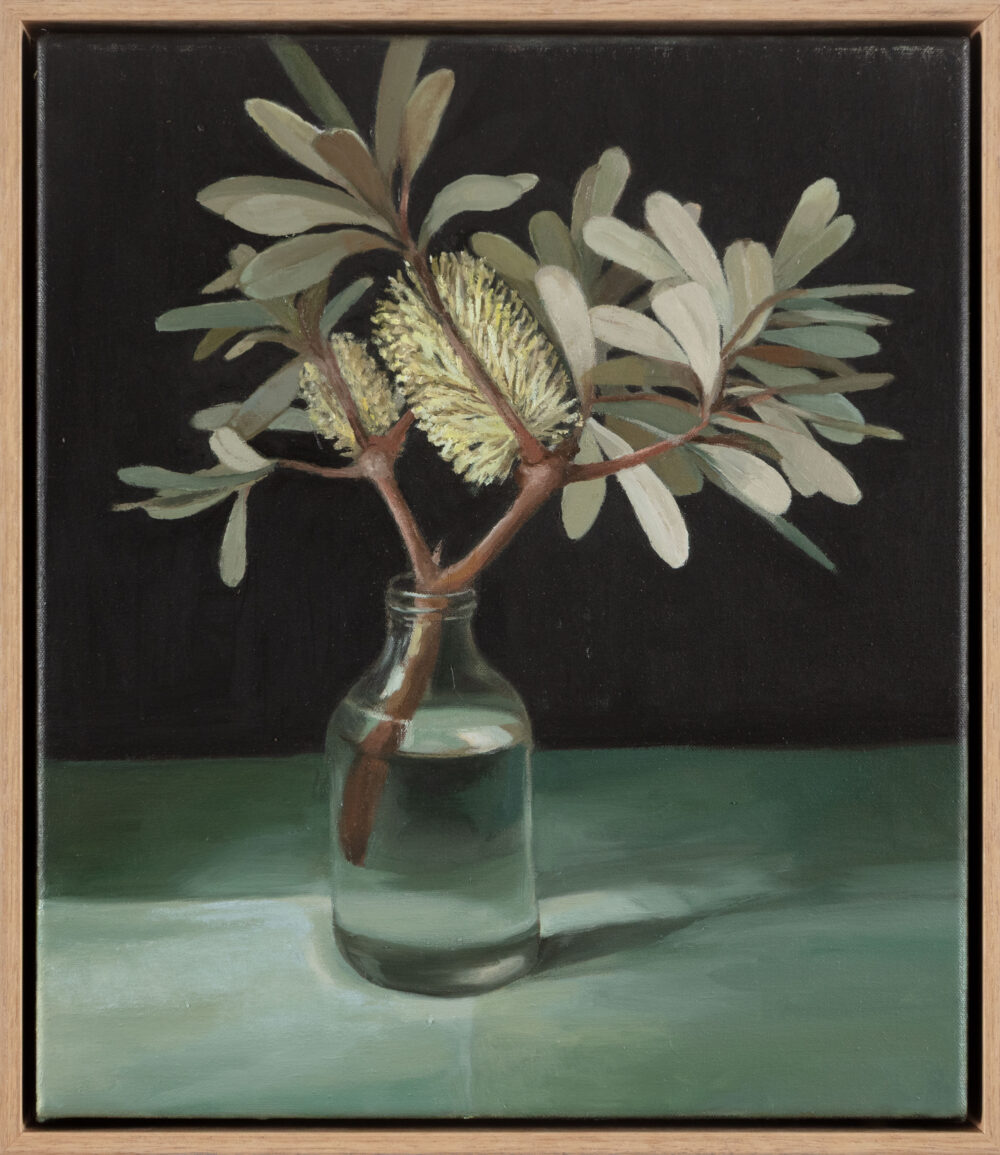

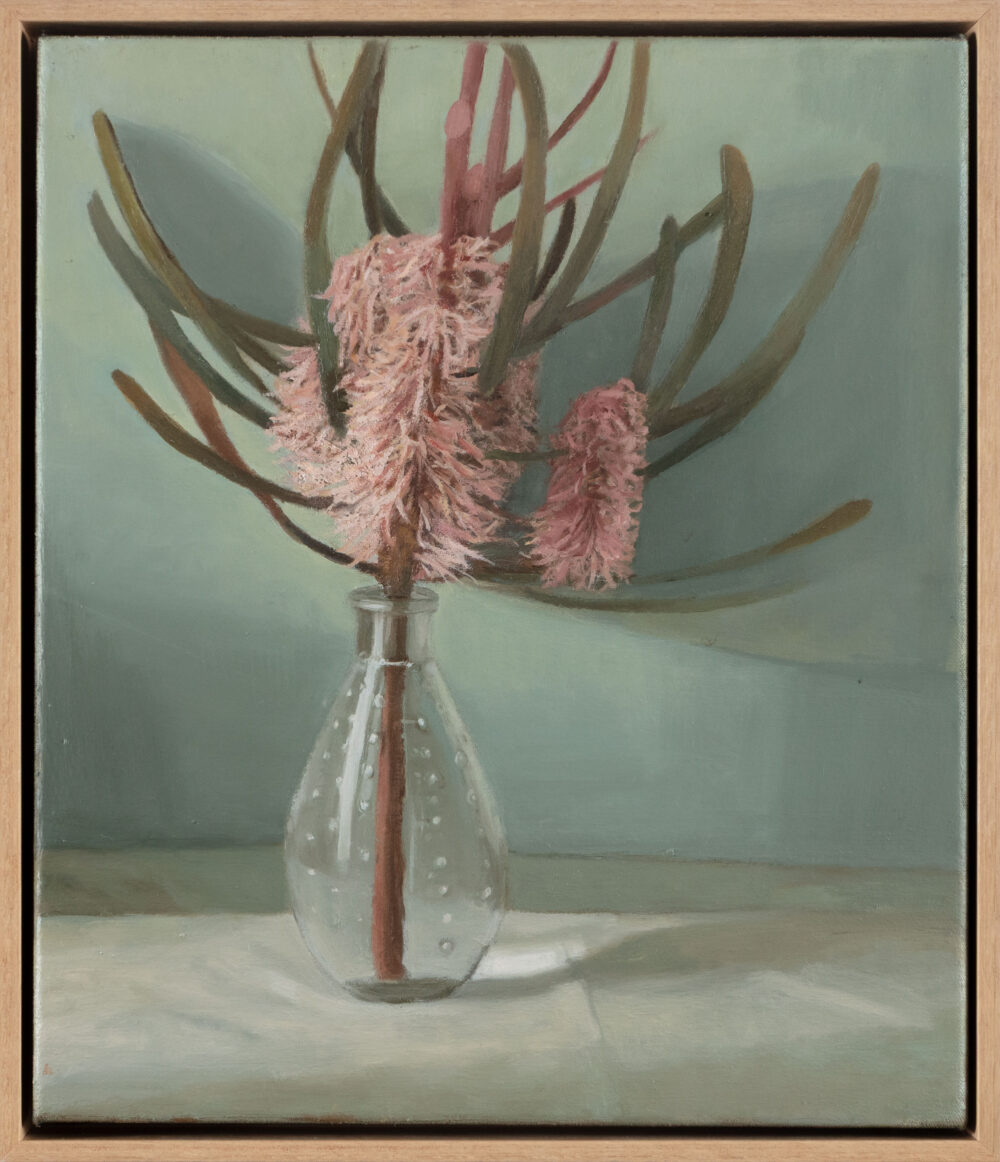

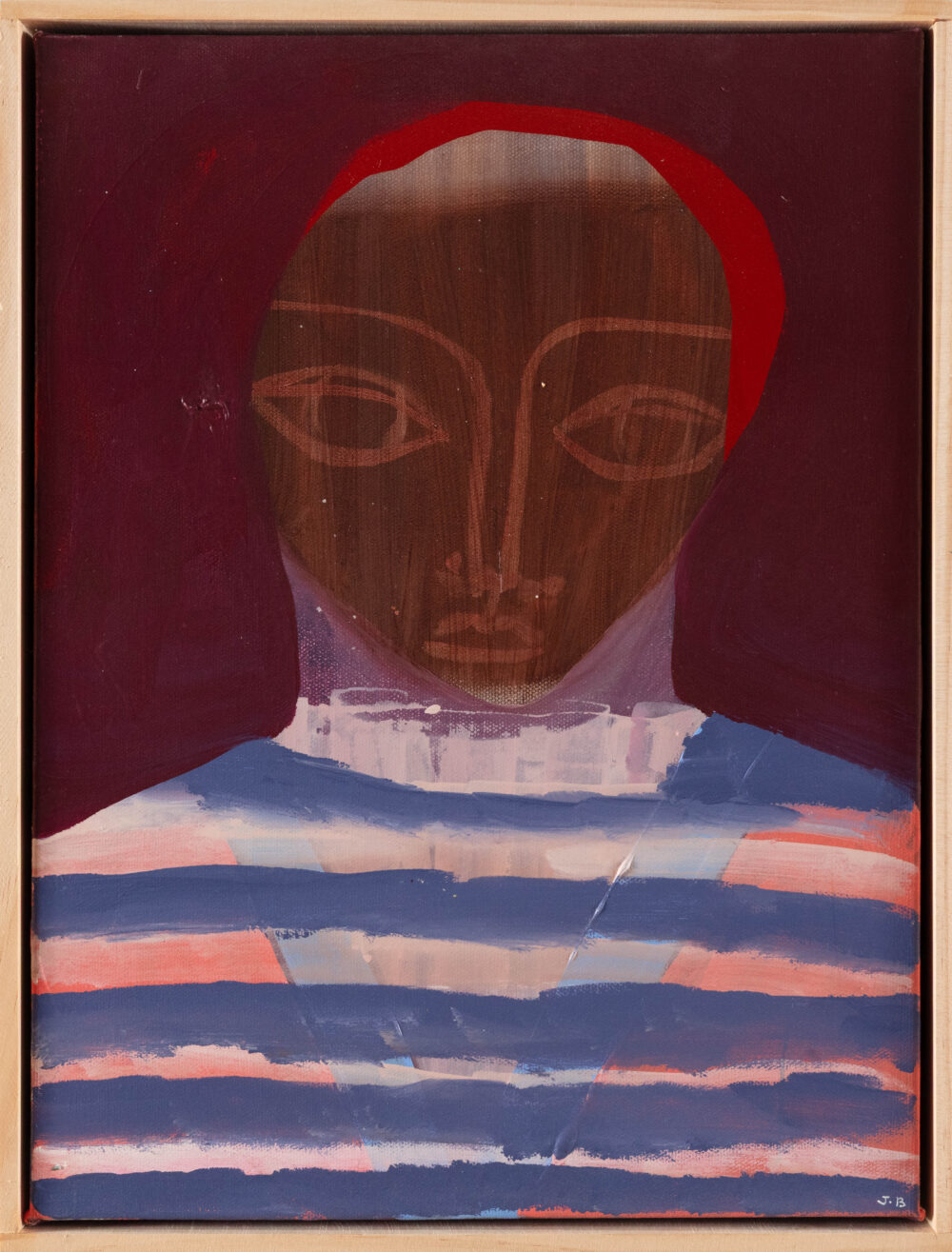

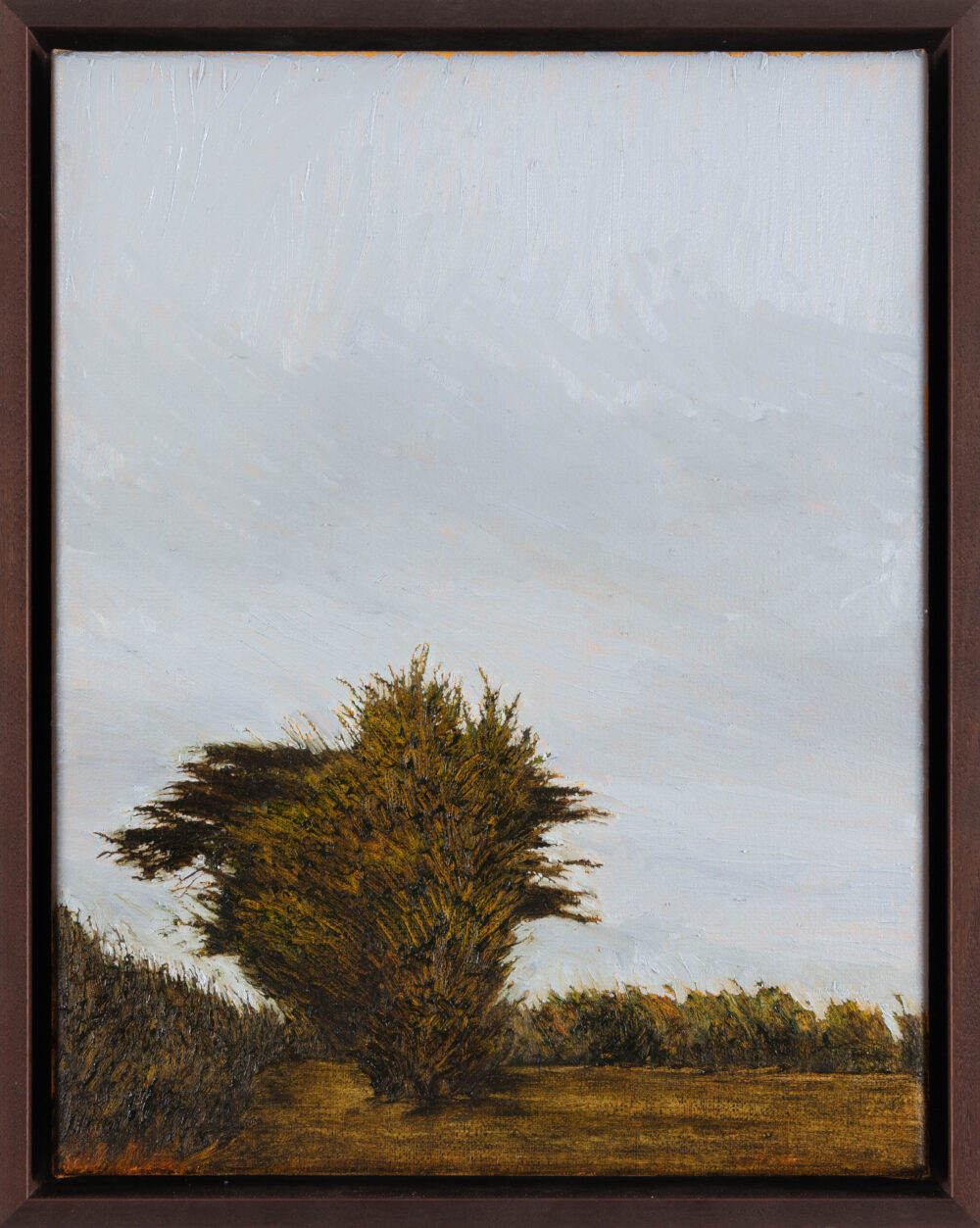

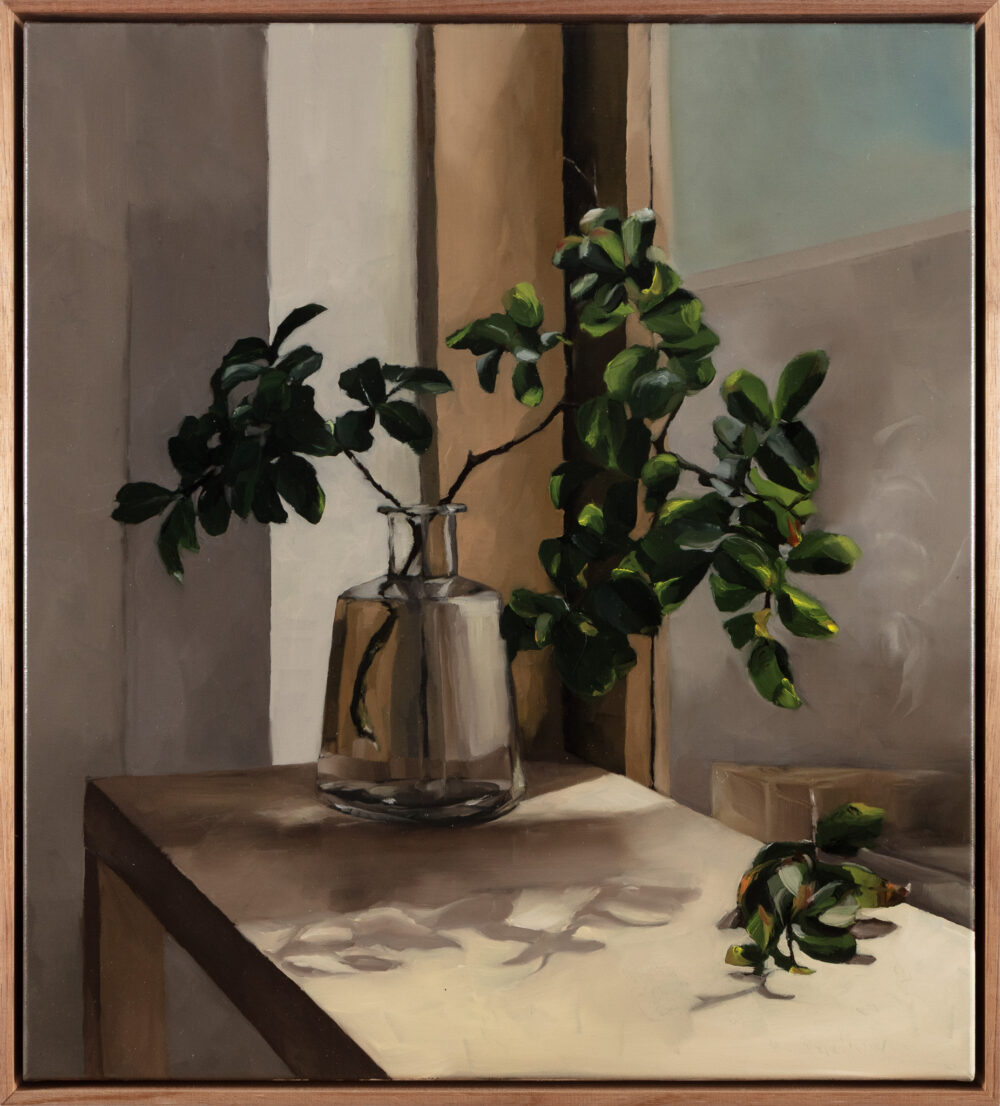

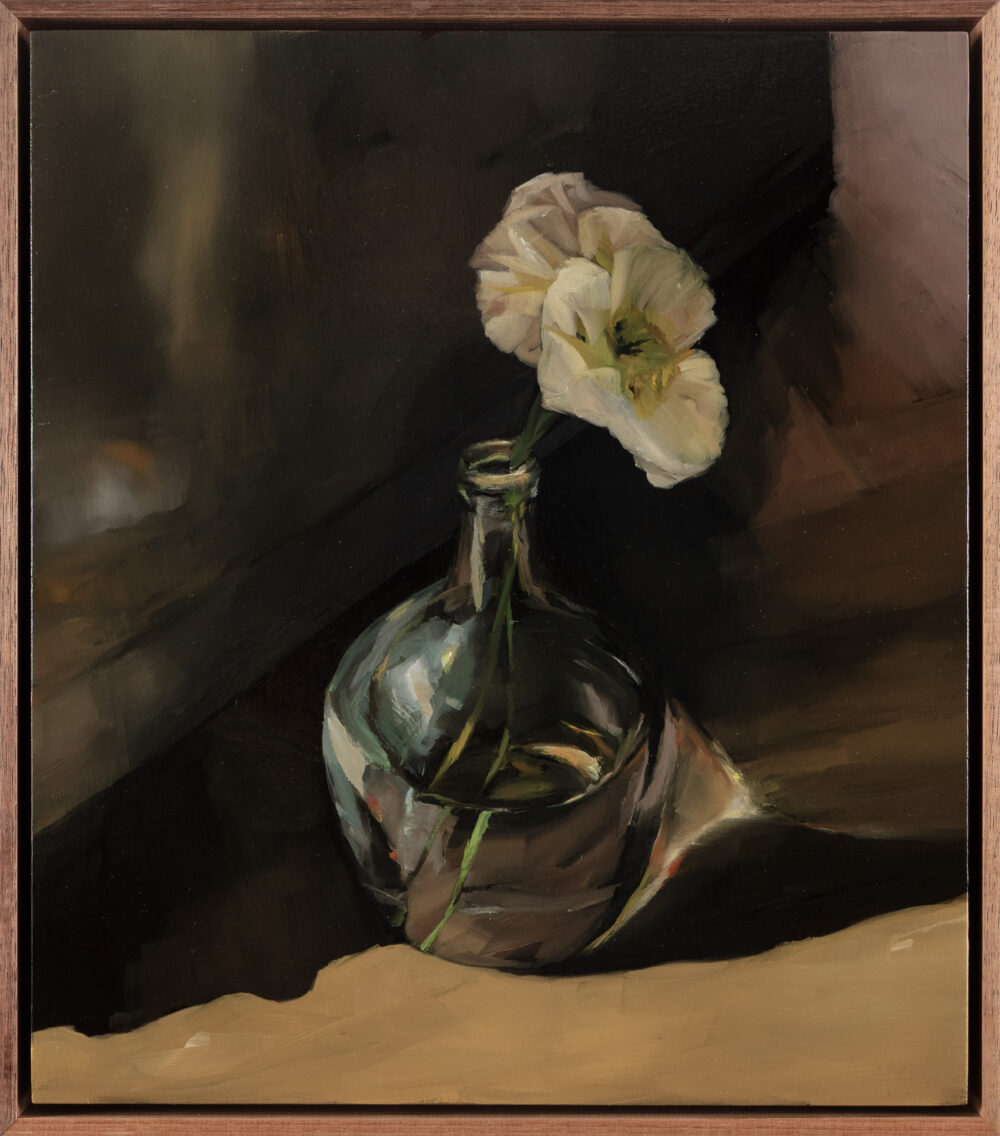

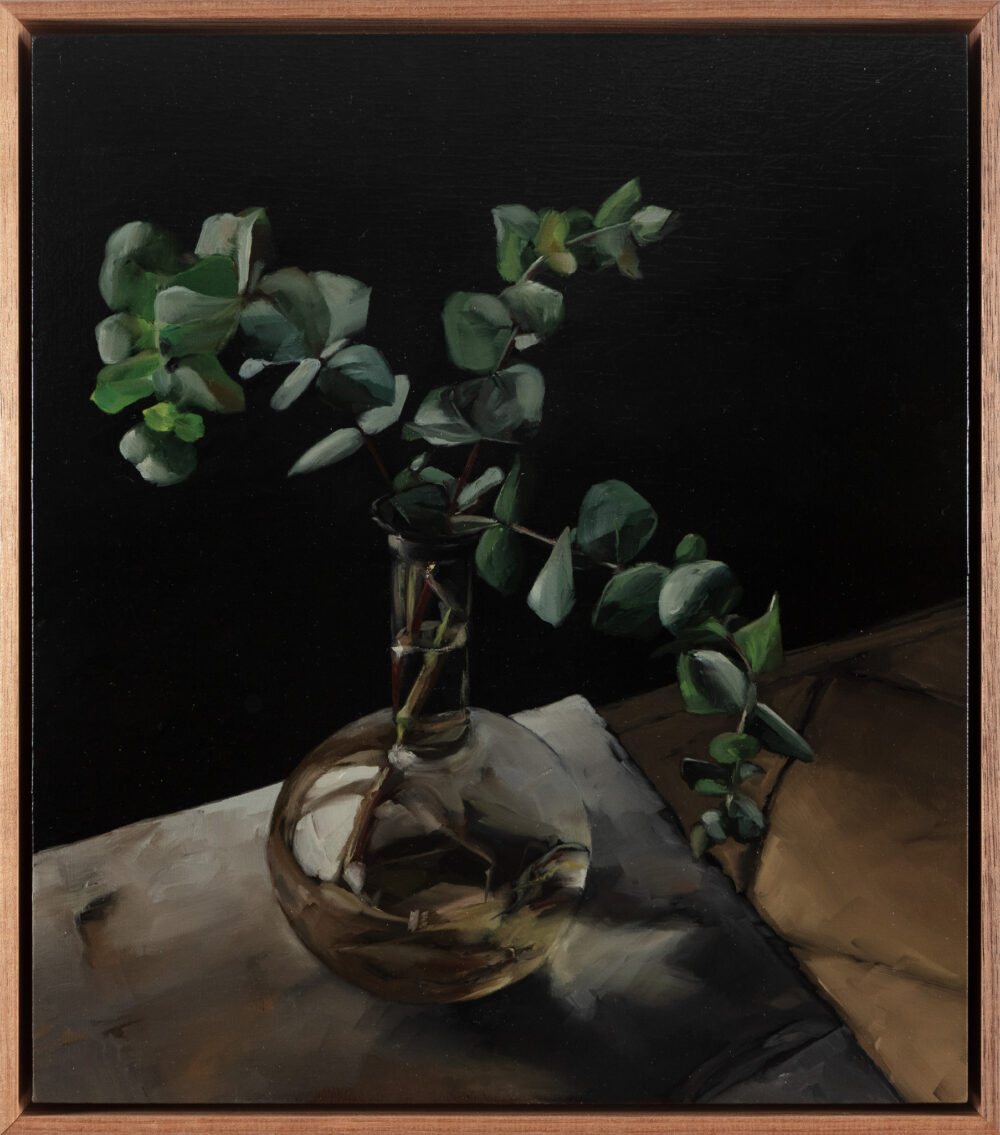

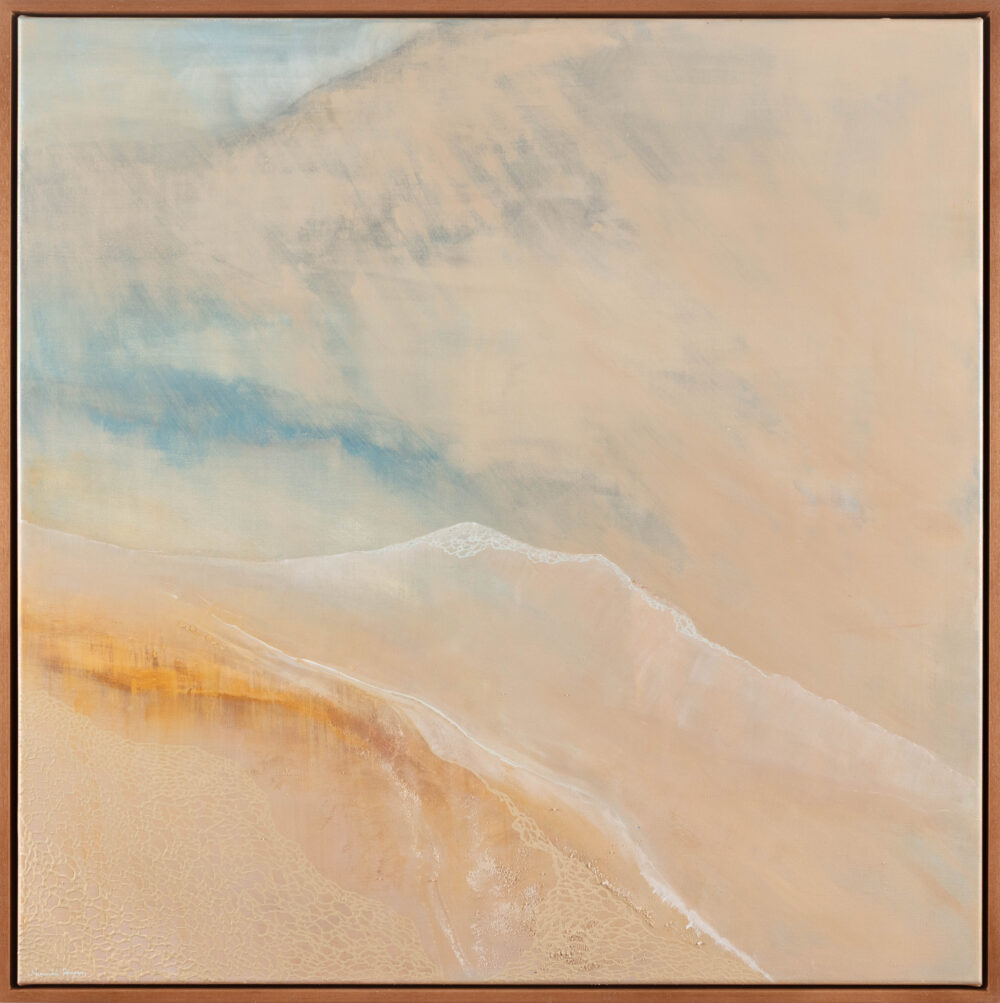

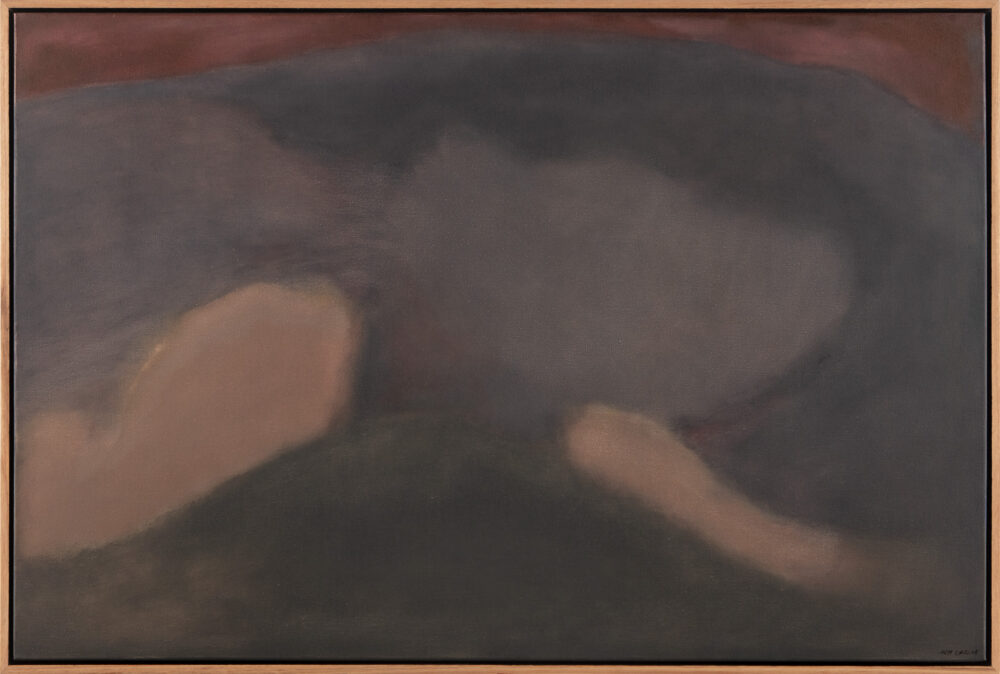

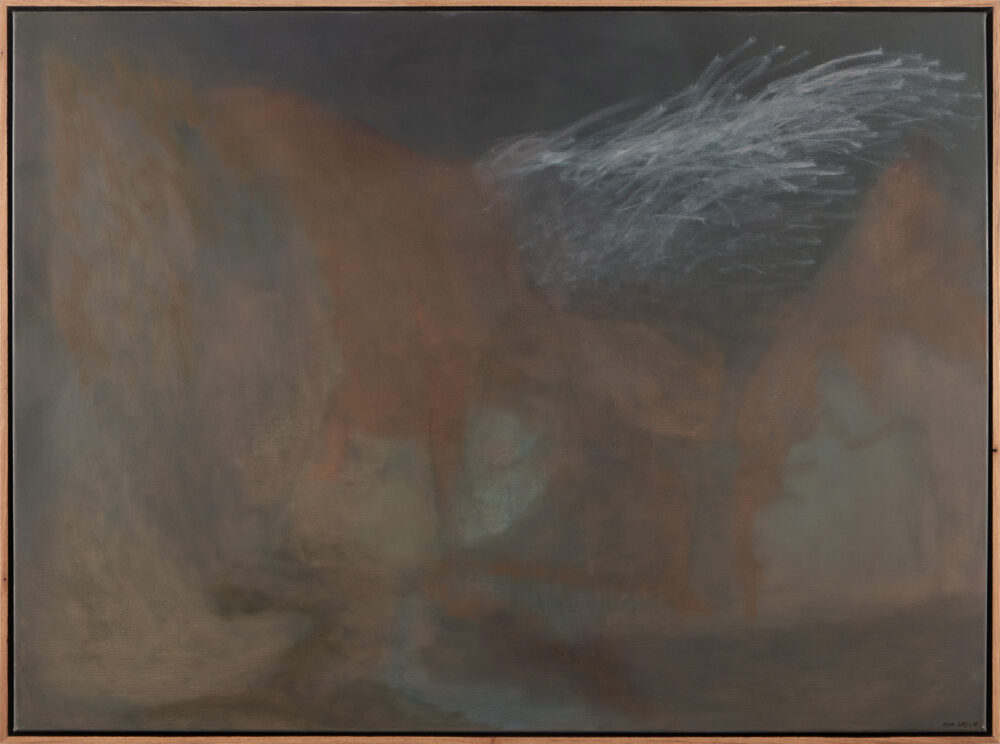

Out of the Blue is a mini-suite of oil paintings emerging from a practice concerned, in essence, with the condition of being human. These works – forming Armelle Swan’s debut with the gallery – aim to characterise, in poetic and intuitive terms, some of the most charged human experiences — grief among them.

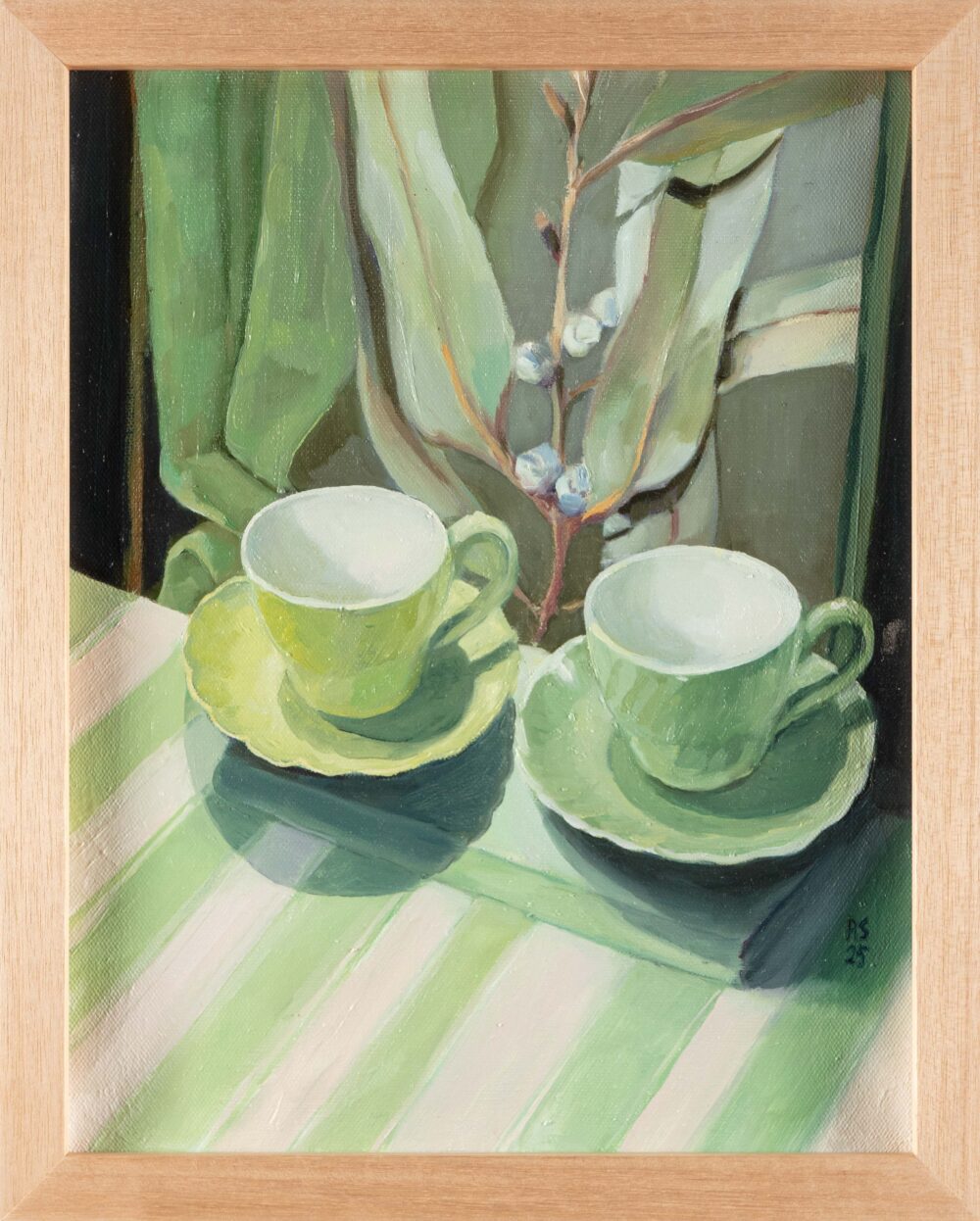

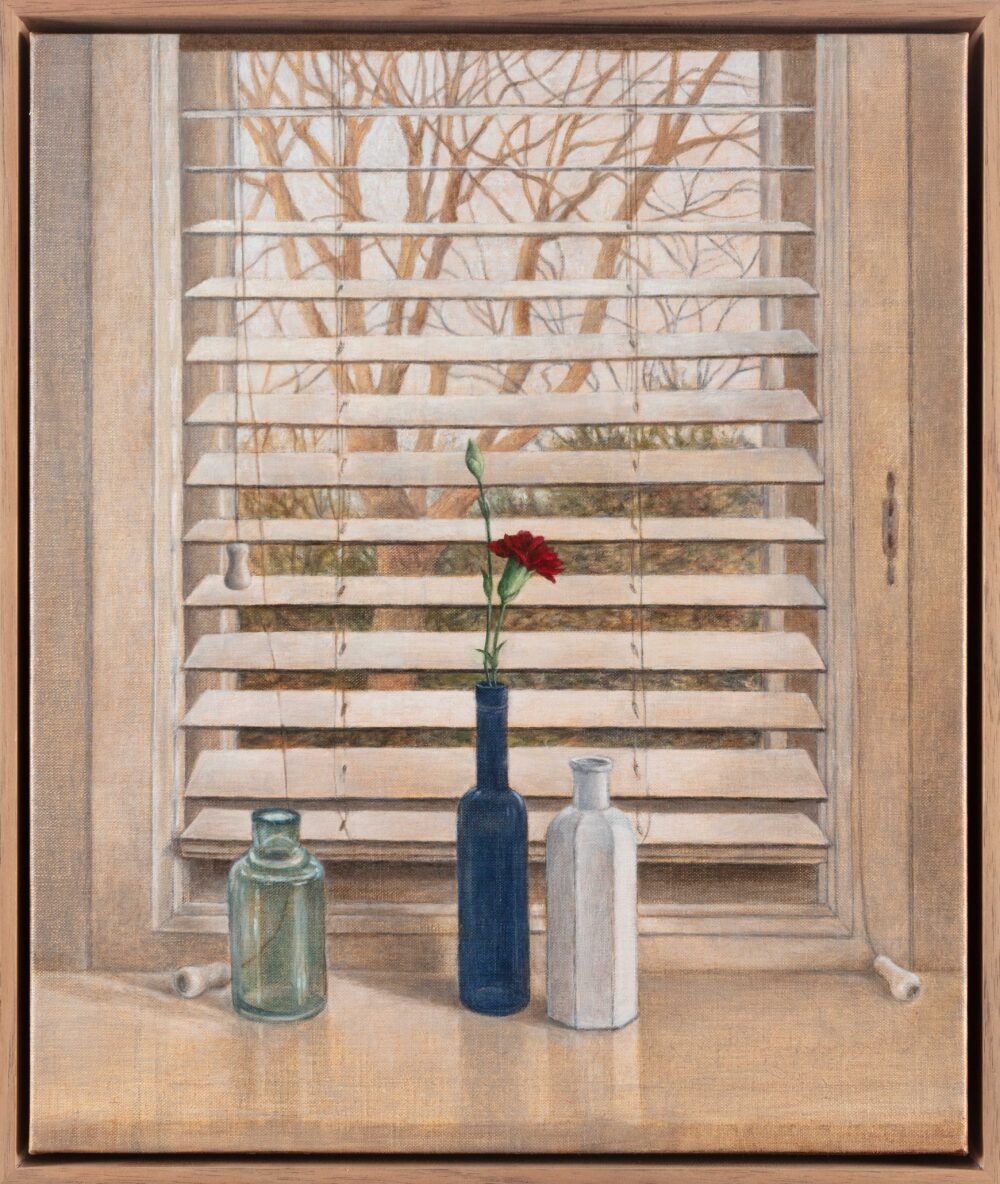

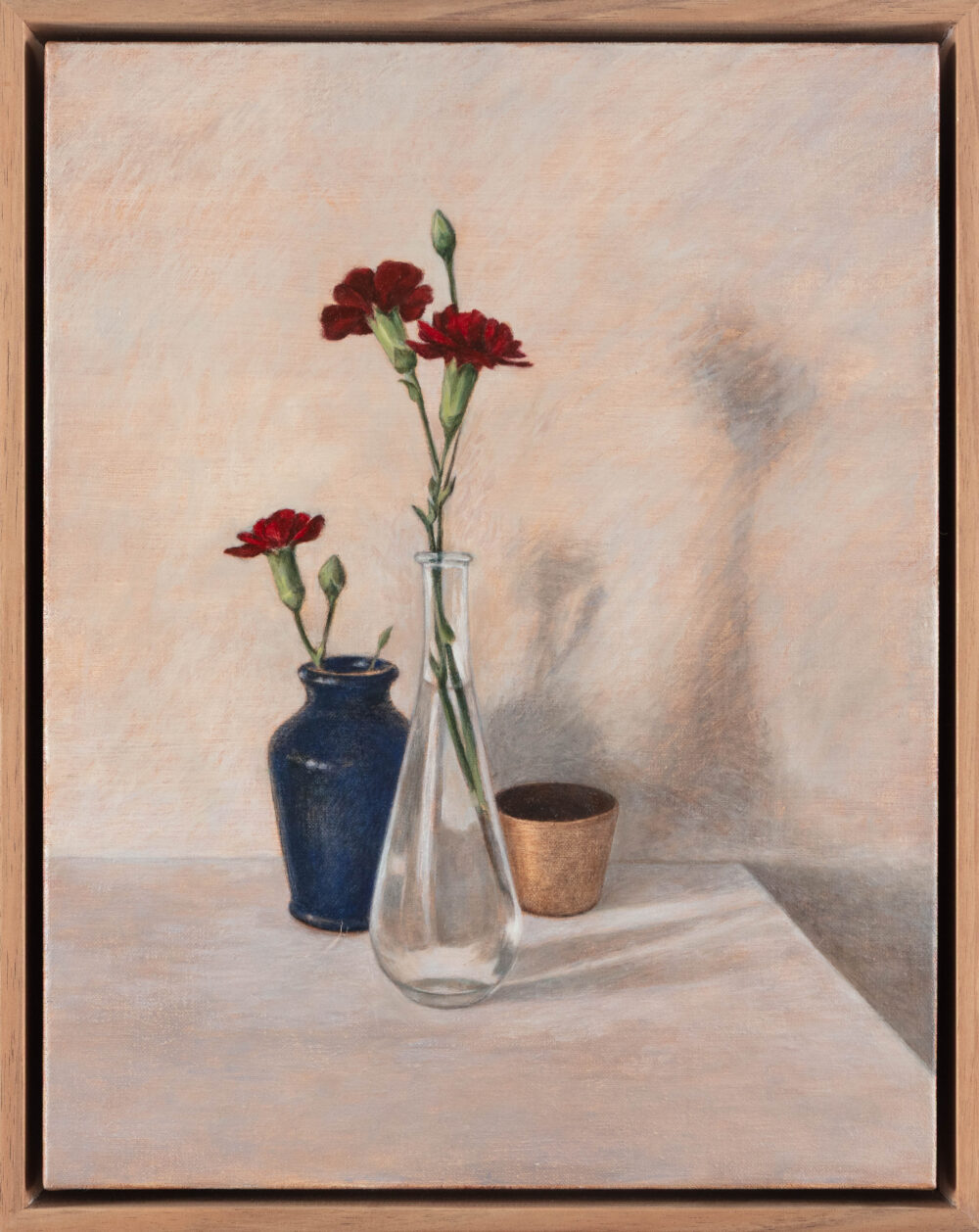

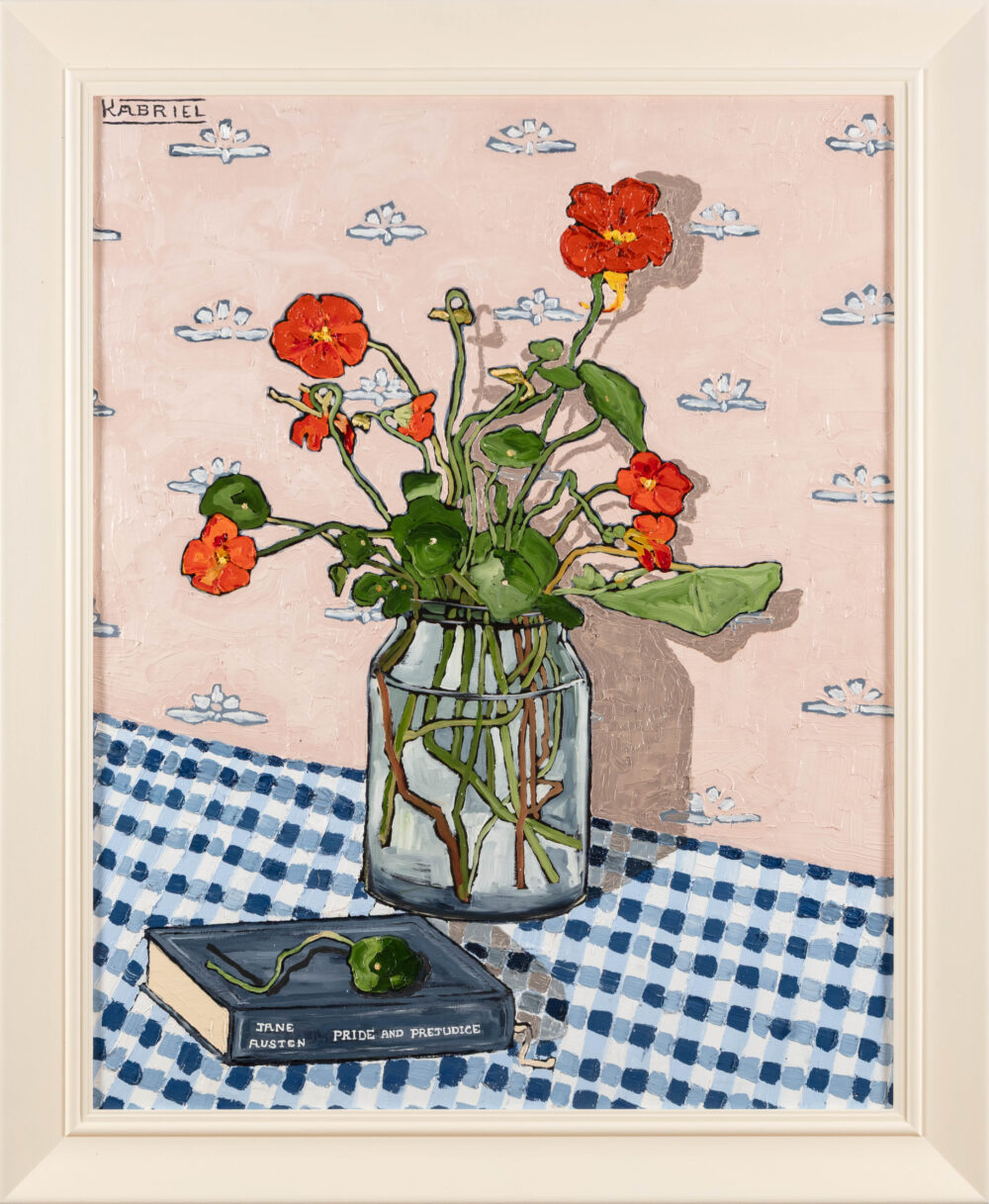

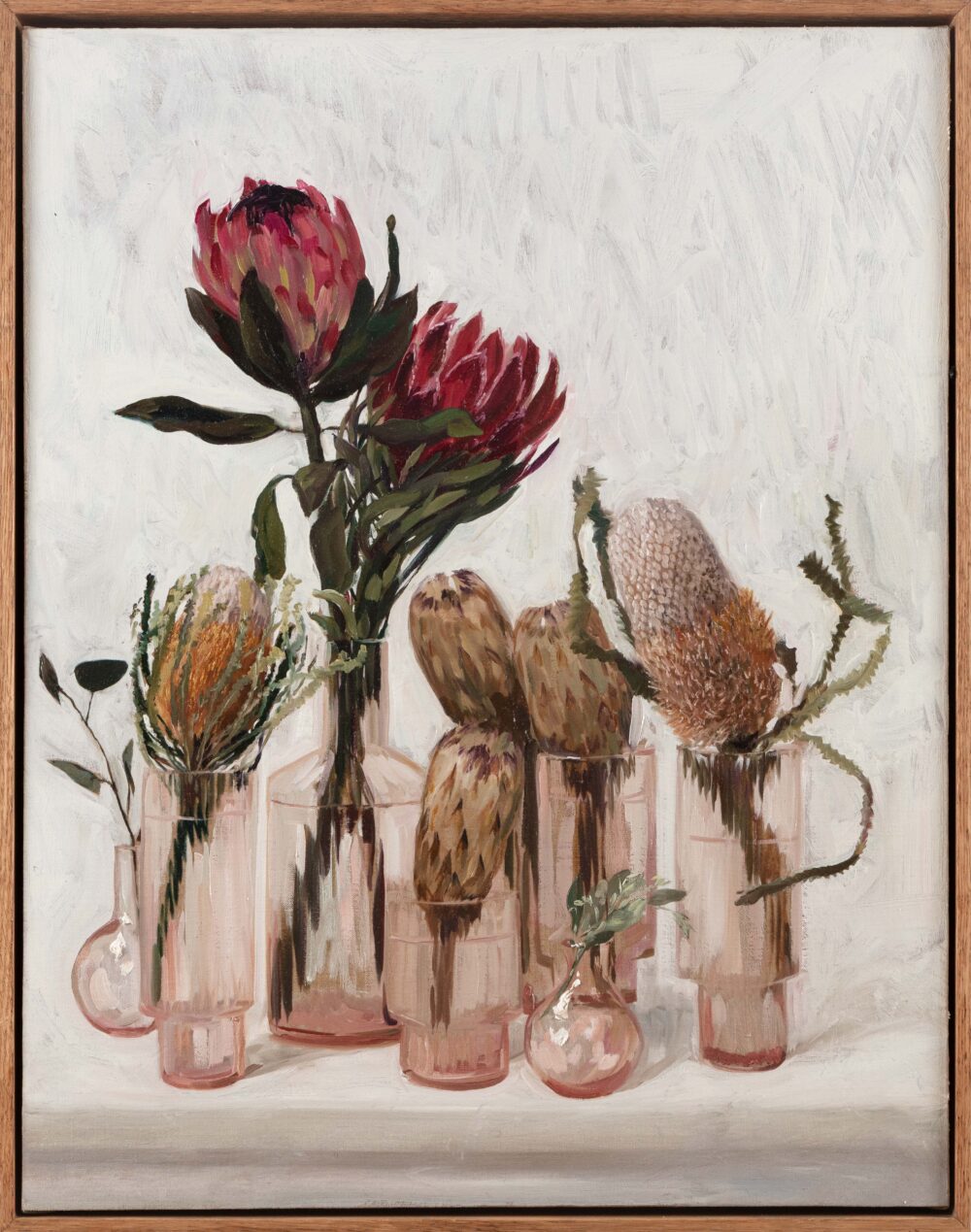

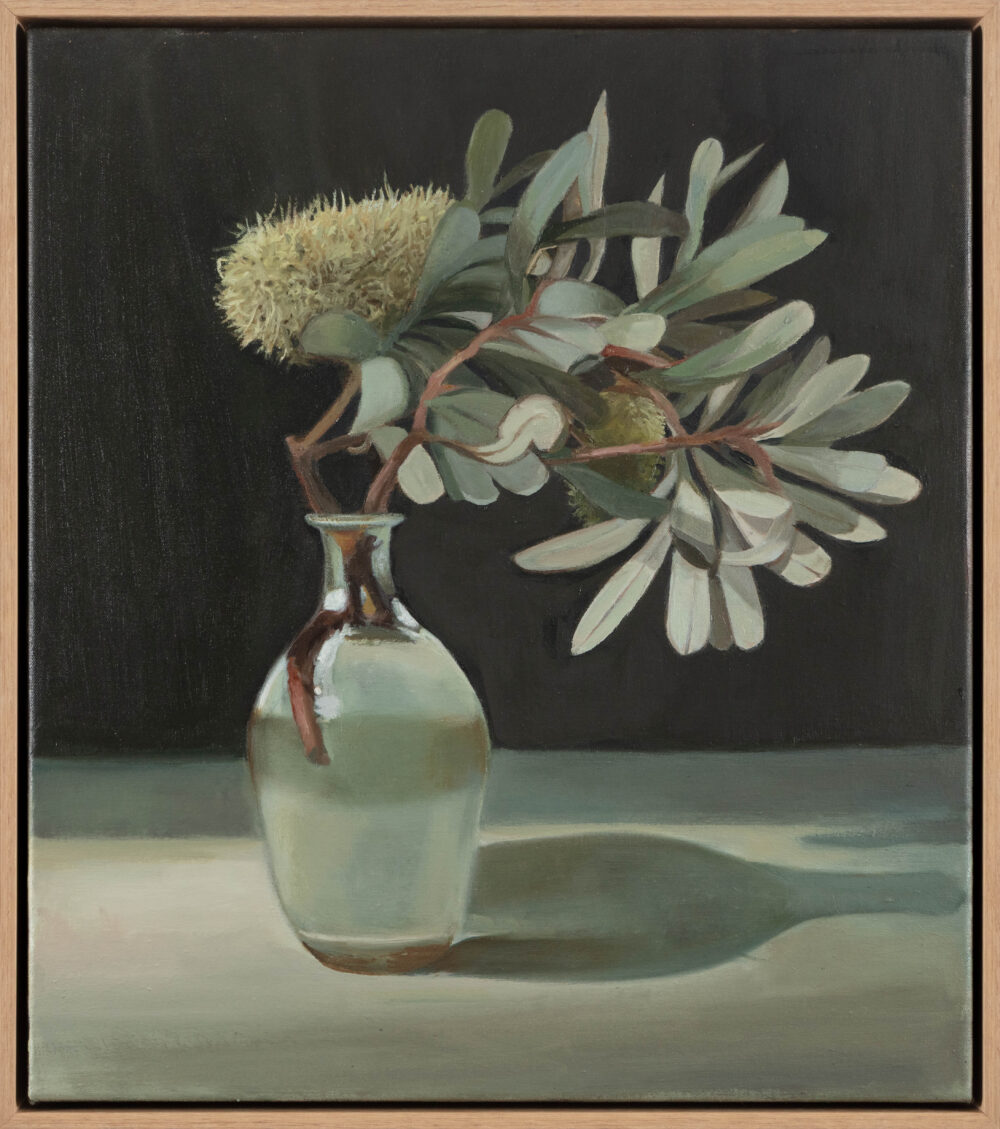

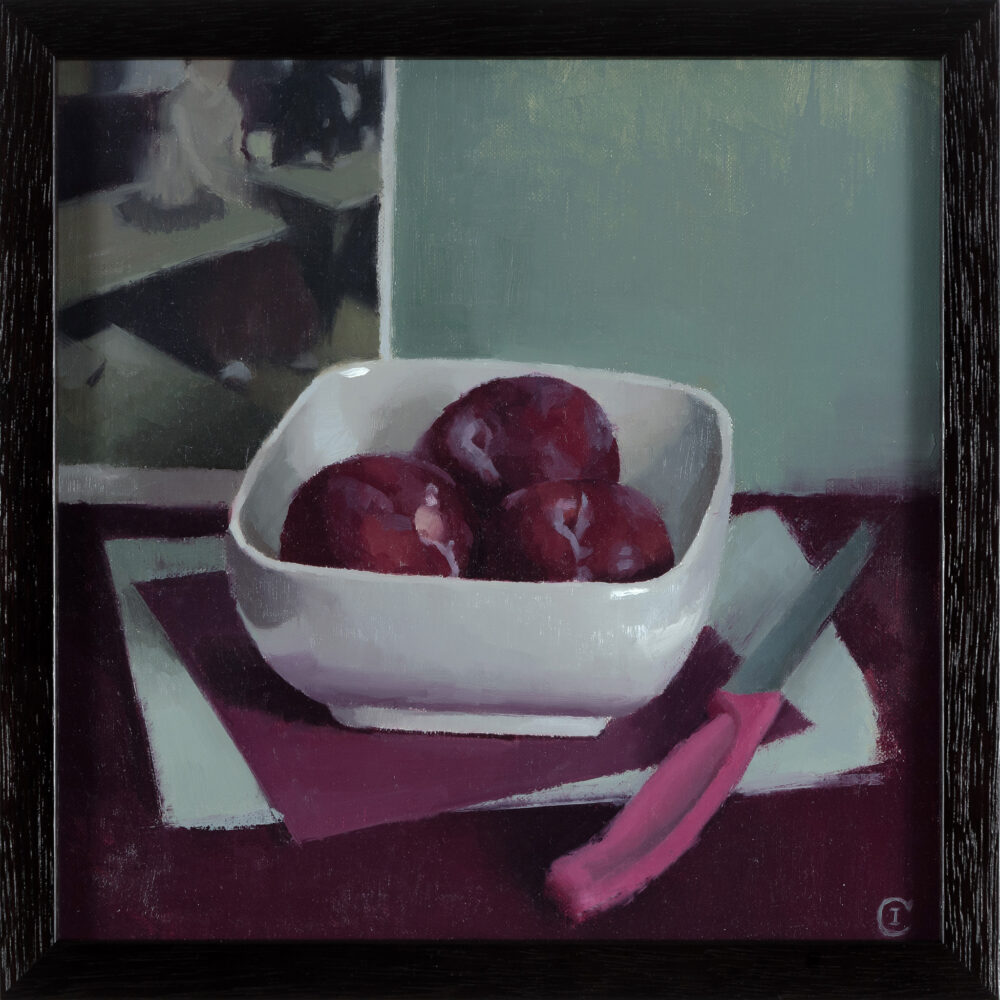

Across the suite, notions of presence and absence recur. In still life the figure is typically absent, yet it may reappear by proxy: a cup, jug or bottle operating as a kind of cipher for the human in the story.

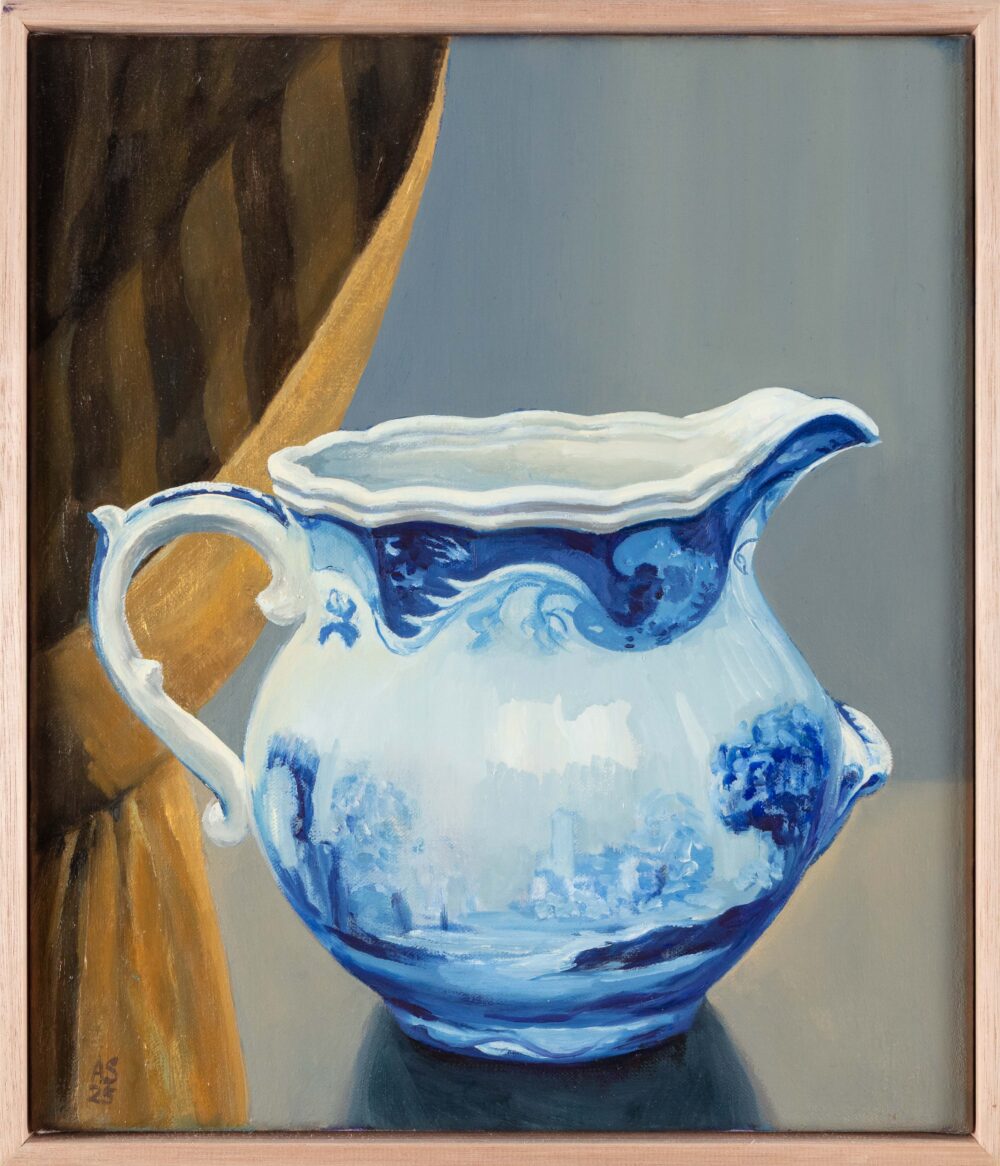

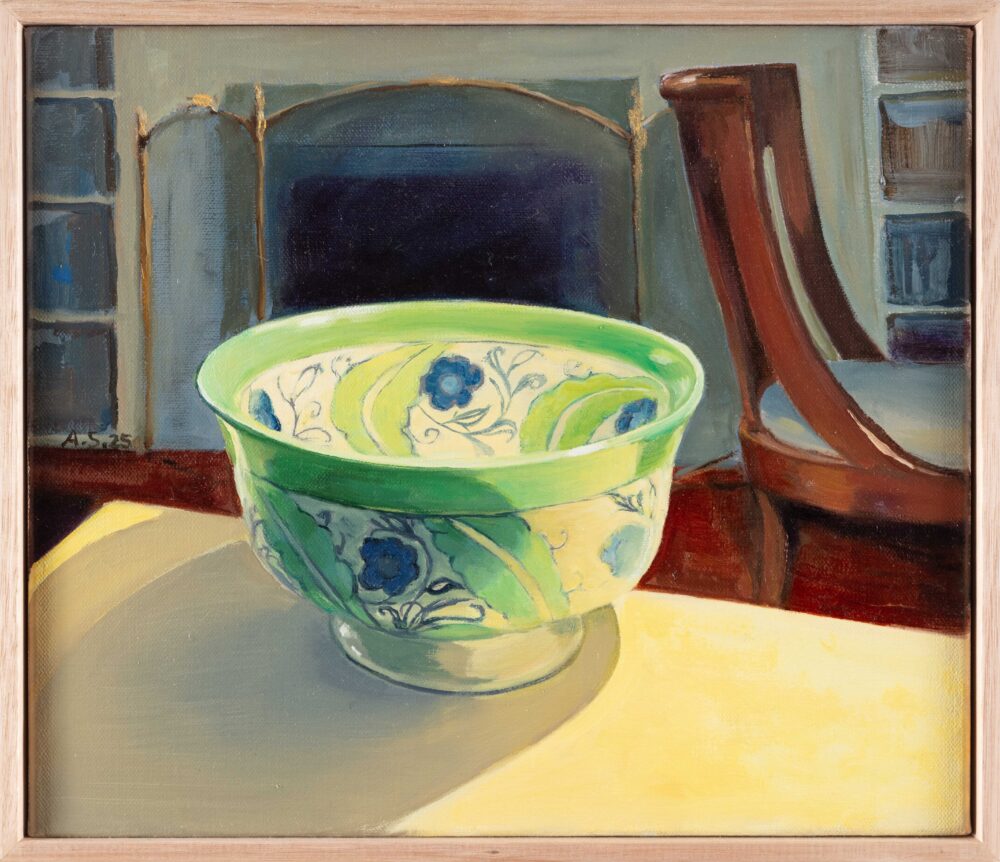

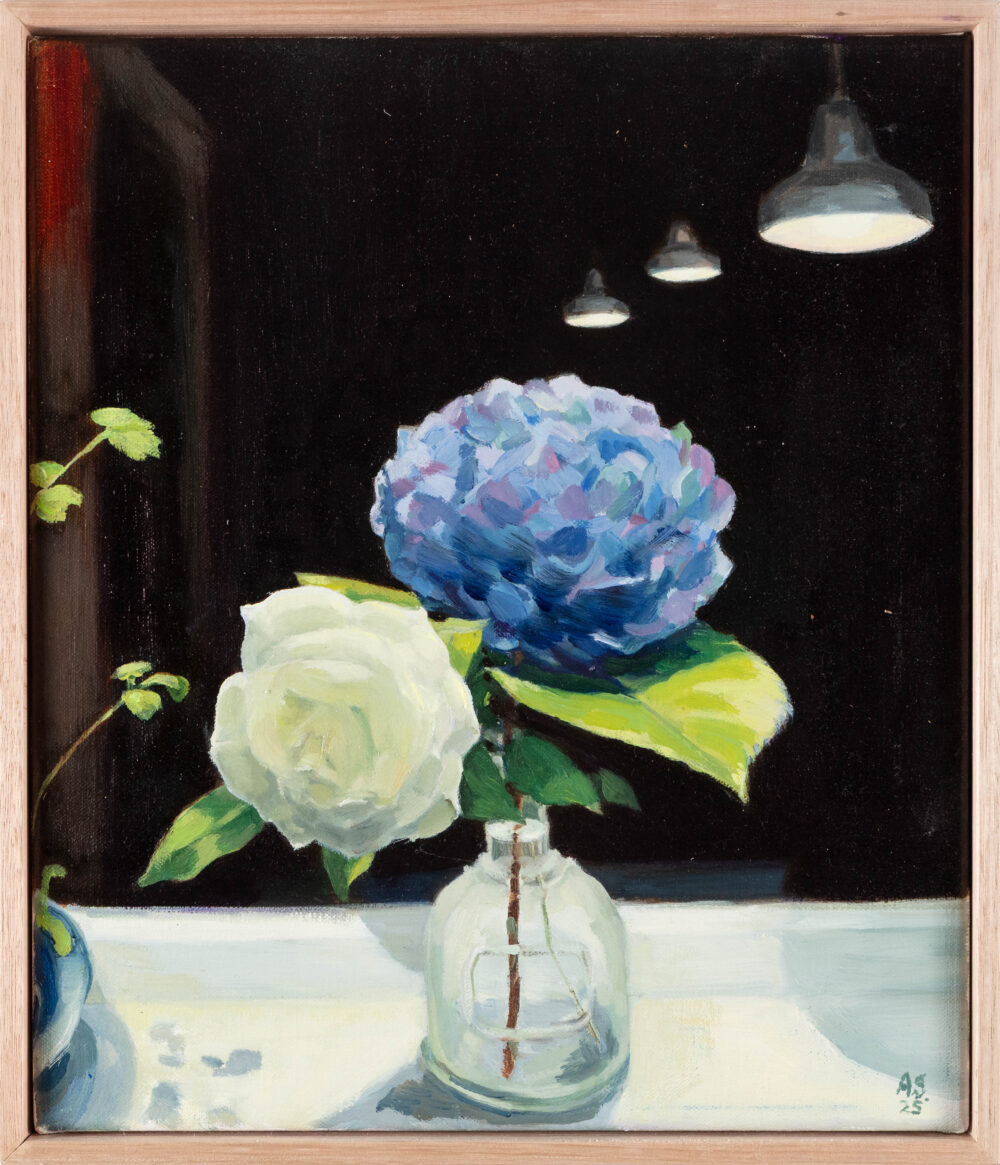

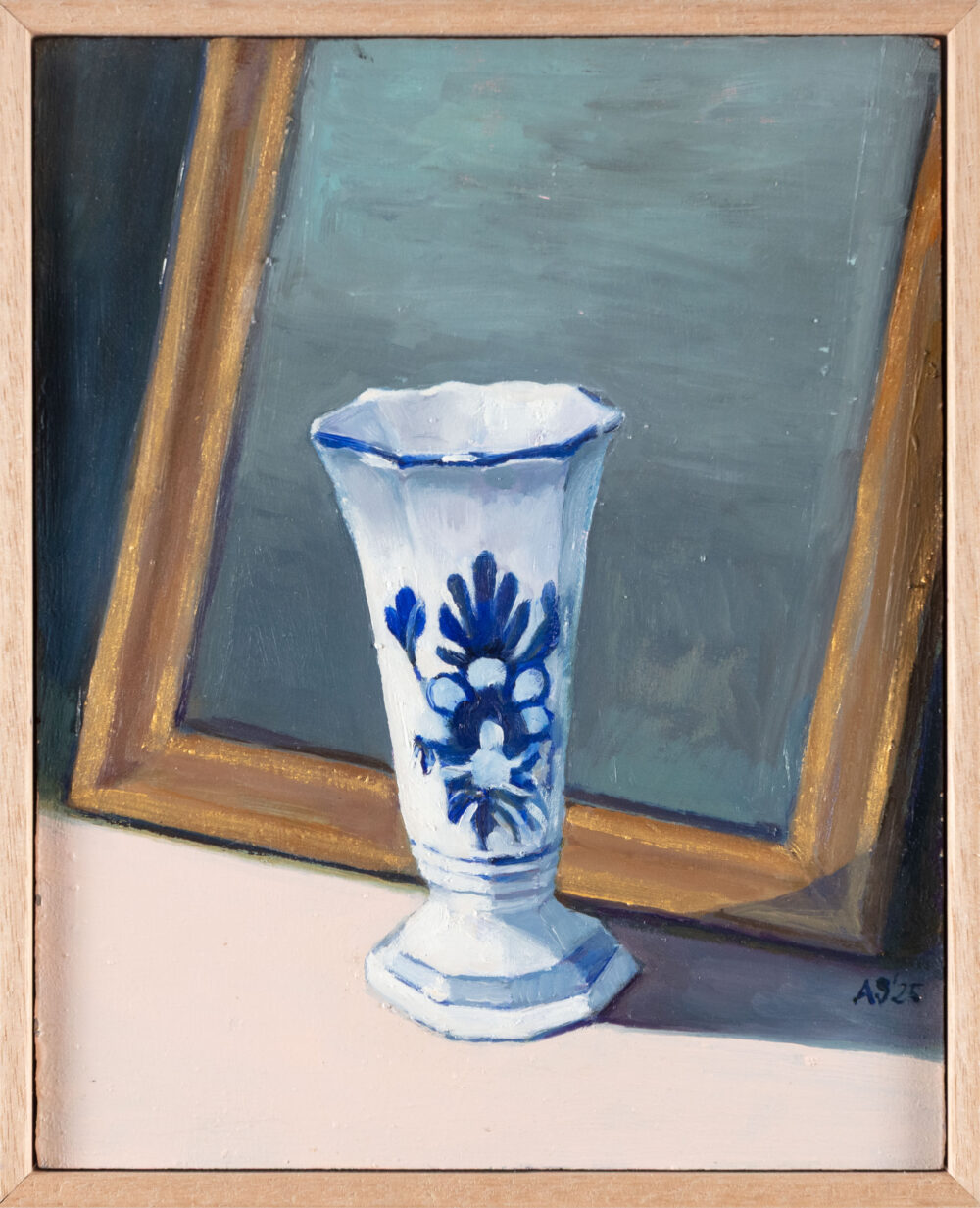

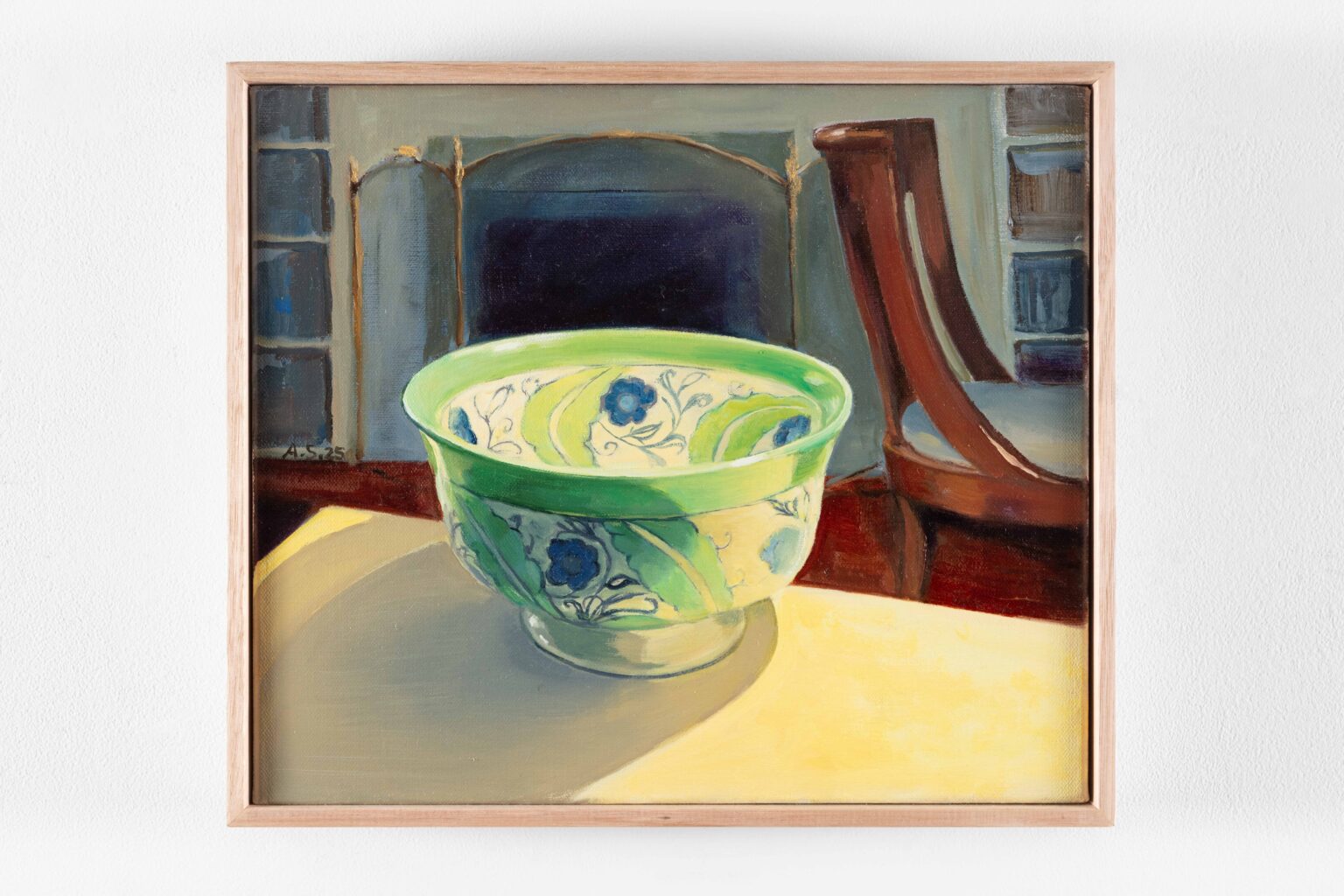

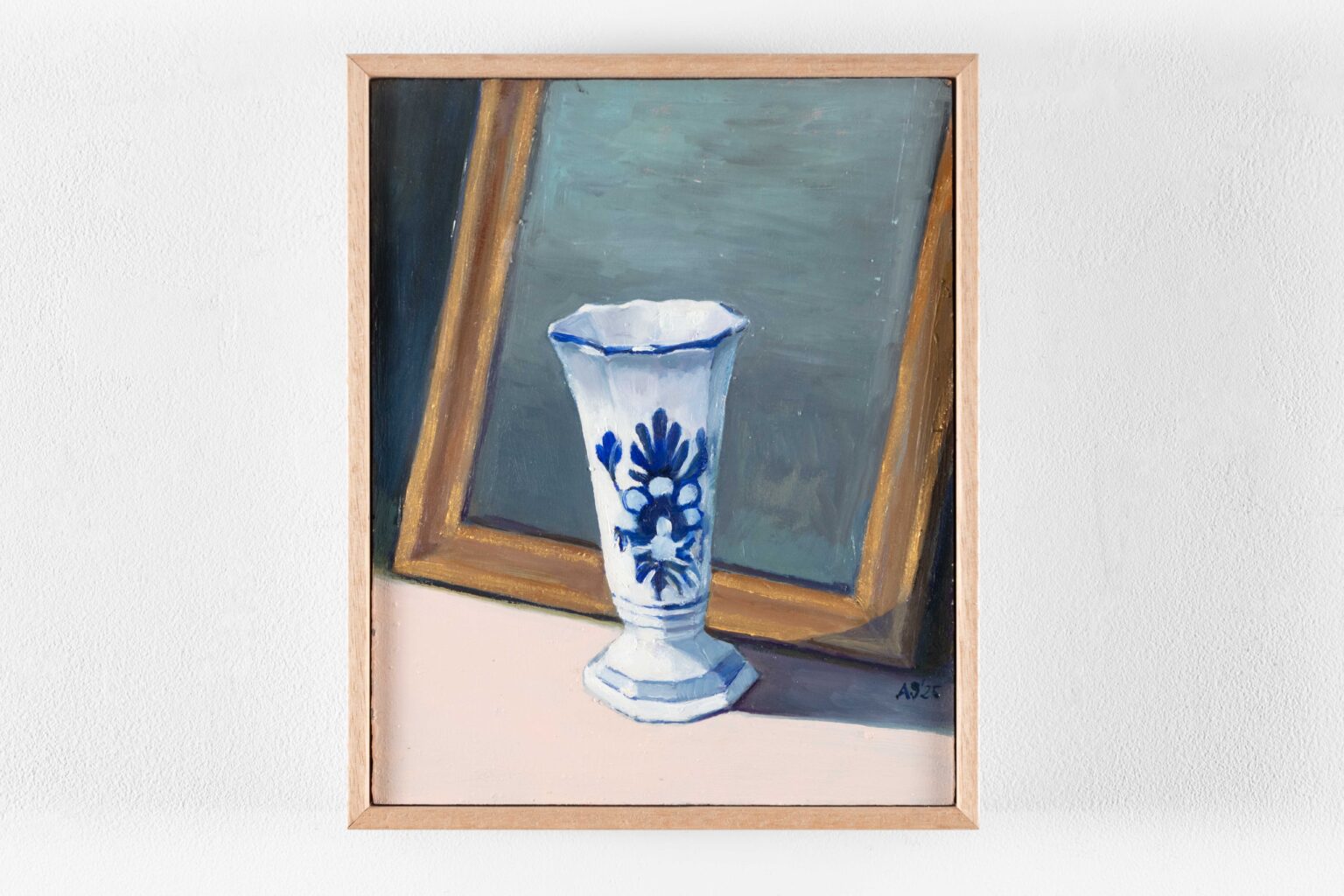

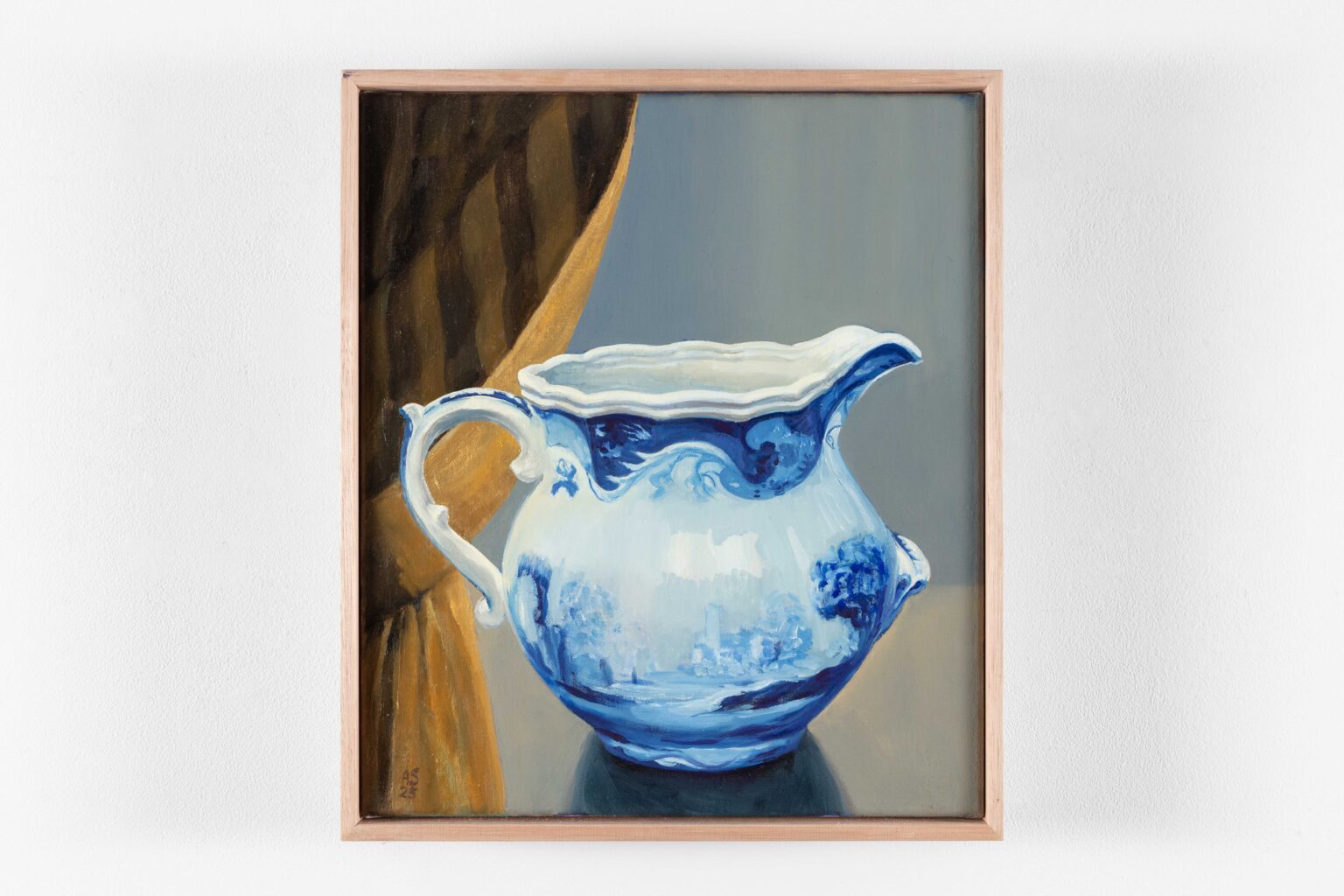

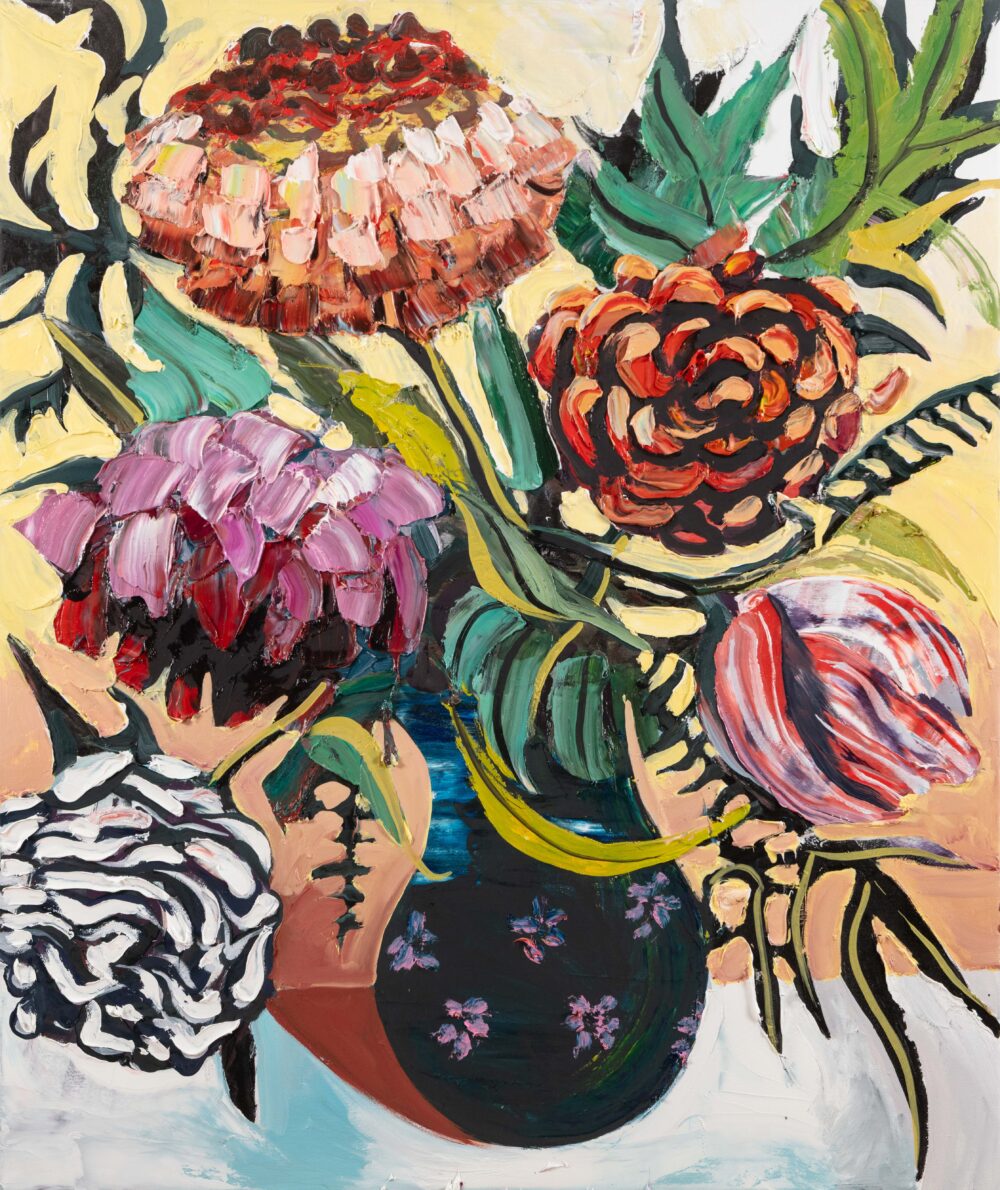

Each work here centres on a vessel — cups, a vase, a jug, a bowl — a motif that since antiquity has carried metaphorical weight, touching on ideas of literal and figurative containment and the human impulse to keep or hold.

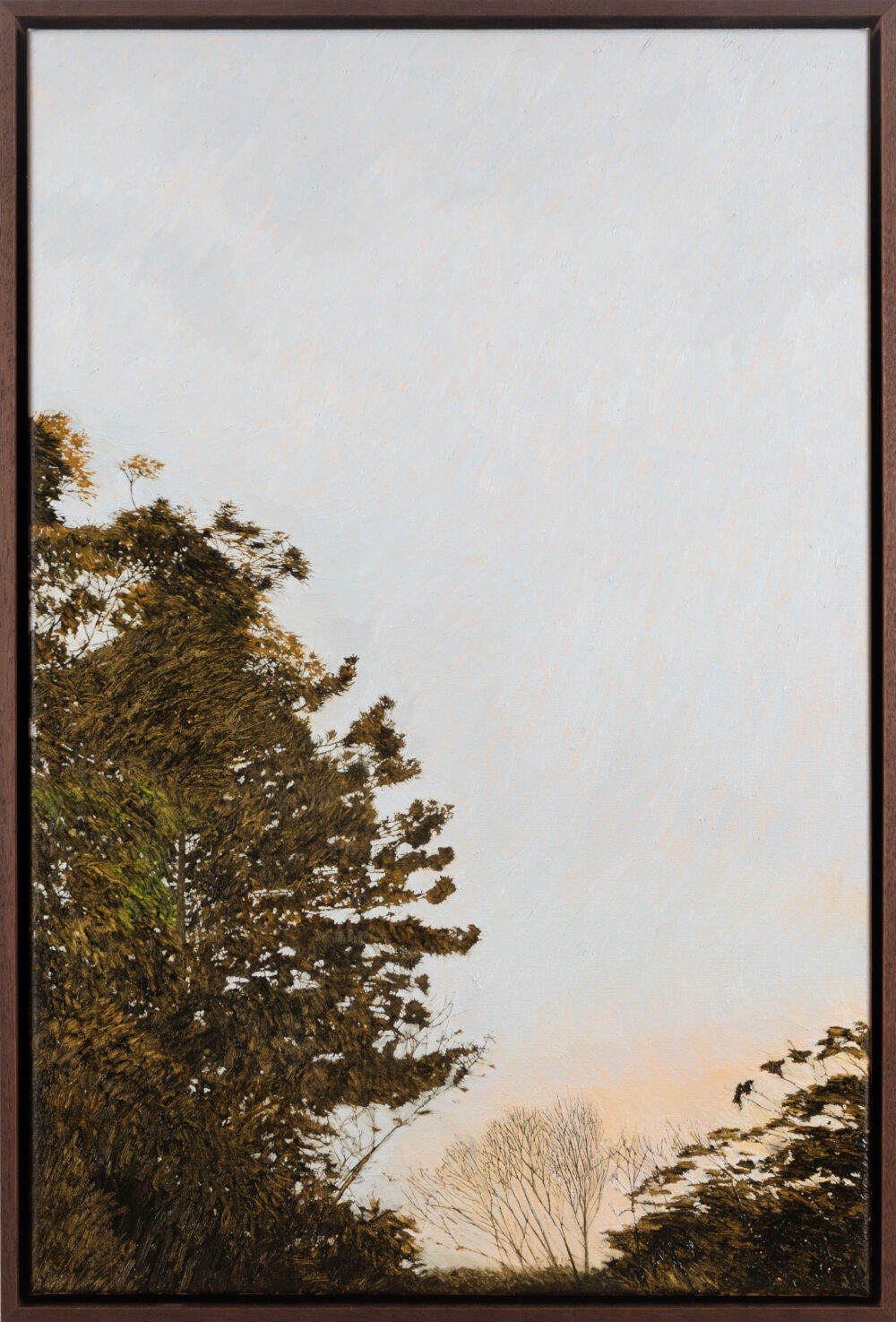

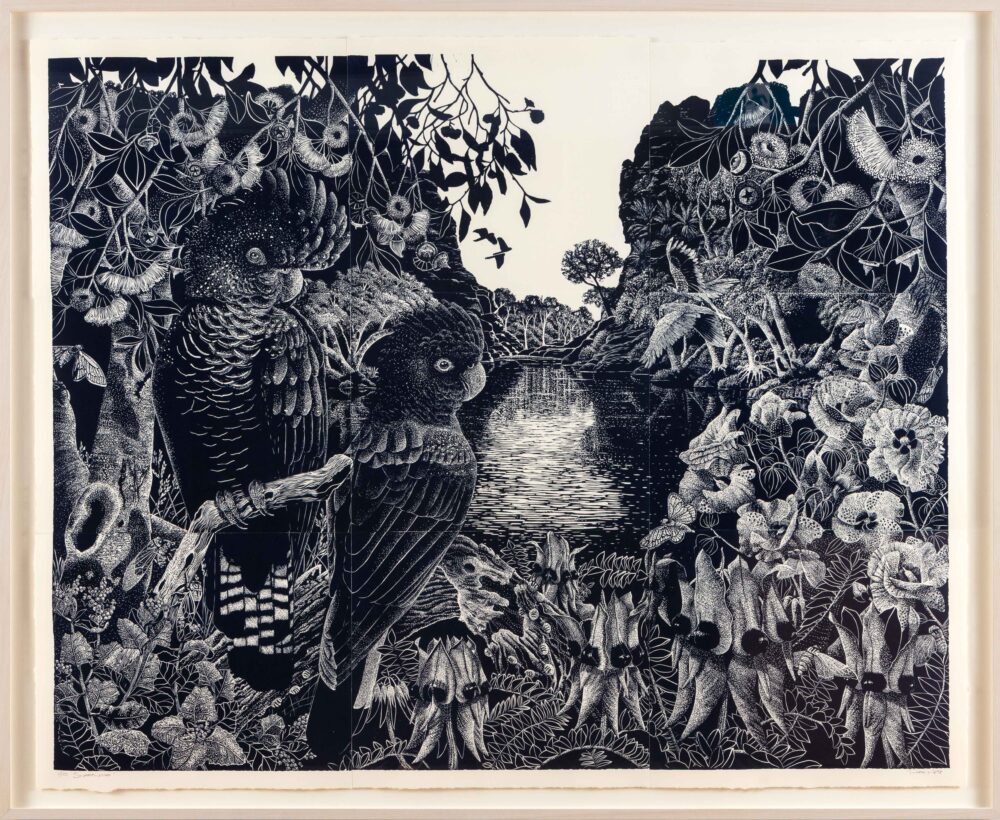

Two works, ‘Not in the Picture’ and ‘Revealed’, feature vessels decorated in blue and white motifs traditionally associated with funerals, death and mourning in Chinese culture. This symbolism sits in neat alignment with still life’s historical relationship to mortality, and with the larger theme of grief within the suite. These elements became newly compelling in Swan’s practice following two life-altering experiences: the recent arrival of a daughter-in-law of Chinese ancestry, and, some years earlier, the death of her own daughter — a loss that precipitated a long and brutal journey of grief. In these paintings, the cultural and the deeply personal converge.

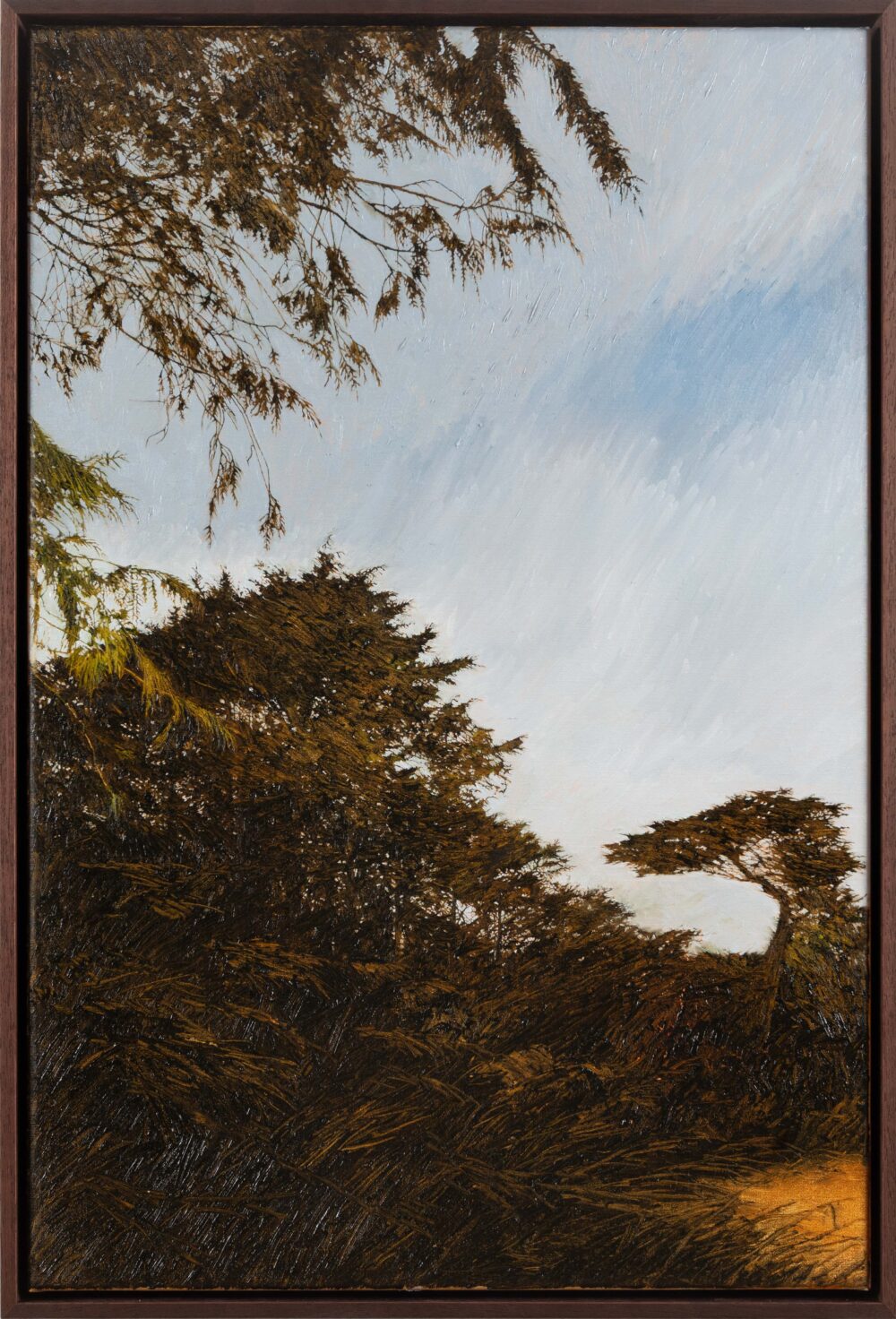

‘Kitchen Sill (after Hopper)’ may appear, at first glance, to depict a simple domestic interior, yet its composition carries a more philosophical charge. The velvety darkness outside, the bright white sill, and the pendant lights reflected in the glass recall the haunting sensibility of Edward Hopper’s Automat. The window becomes a threshold: a meeting point of dark and light. The reflected lights appear to move from the interior into the night, piercing both the window pane and the picture plane as they recede like a row of distant streetlamps. As ever, the window is an ‘eye’ that sees, and the view it frames echoes the act of painting itself.

‘Glow’ offers an interior heightened by a keen register of attention — a meditation on observation and presence.

Armelle Swan has exhibited in group and solo shows, completed numerous portrait commissions, and been a finalist in several awards, including the Waverley 9 x 5” (twice), the Kings School Art Prize, the Harden Landscape Prize, and various portraiture and still life prizes. Highlights include curated exhibitions such as ACB Selects (2023), The Making Effect for the Arts Health Association NSW (2020), and Dot, dot, dot… (2017) at Sydney College of the Arts Galleries.

In 2019 she undertook a study tour of Italy with Dr Julie Fragar, and in 2023 completed a major arts–health commission for SPHERE Knowledge Translation, creating works based on her interpretation of academic health-study findings. Her works are represented in private collections in Australia, South Africa, the UK, Dubai and Singapore, and in public collections including the Young Endeavour Youth Scheme, the Archdiocese of Hobart and the Black Dog Institute.