Melanie Waugh

Melanie Waugh is a painter of landscapes, but not the polite, manicured kind. Her brush strokes are quick and confident, capturing not just a scene but a sensation—a moment when the air is thick with heat, or the earth, newly wet, clings to your boots. Her recent work, exhibited at Michael Reid Southern Highlands under the title High Country, is rooted in the rugged terrain of Cathedral Rock National Park. Waugh’s paintings are not about nature as an abstract concept; they are about specific places that hold the weight of personal history. “I like painting places that are familiar to me or special to me—places where I go to breathe,” she says, and the viewer, too, feels drawn into this inner geography.

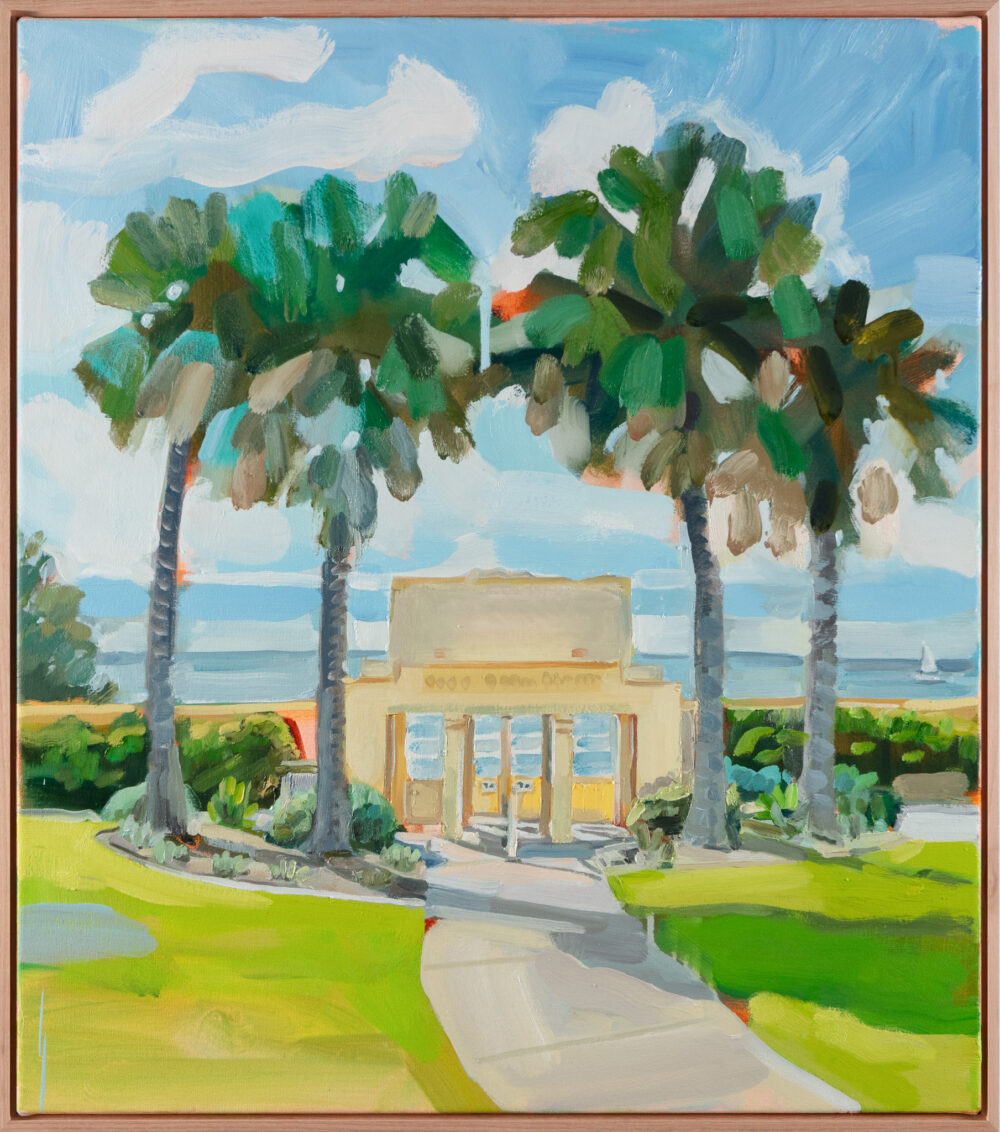

Melanie Waugh

Oak Park, 2025

85 x 75 cm

$2,800

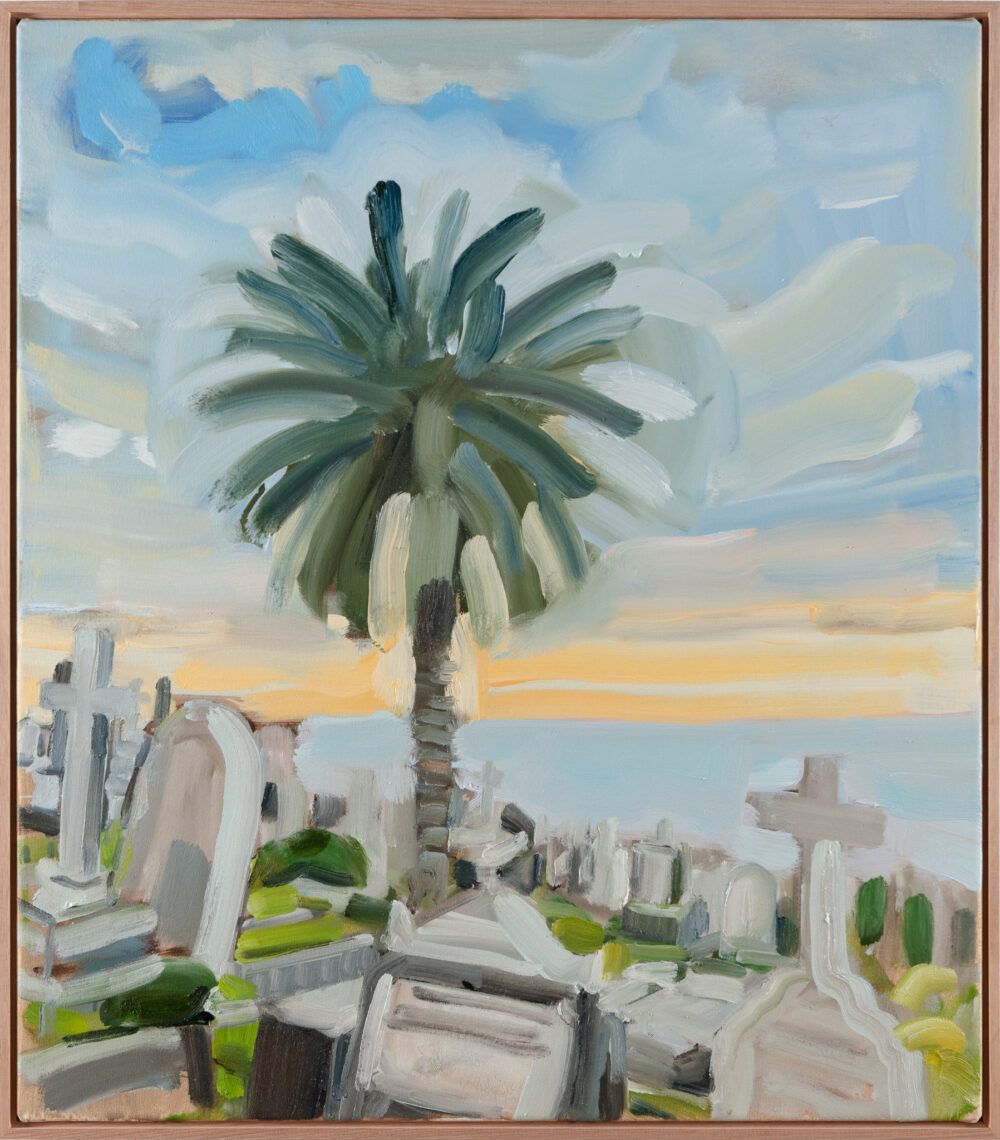

Melanie Waugh

Hornby Lighthouse, 2025

85 x 75 cm

$2,800

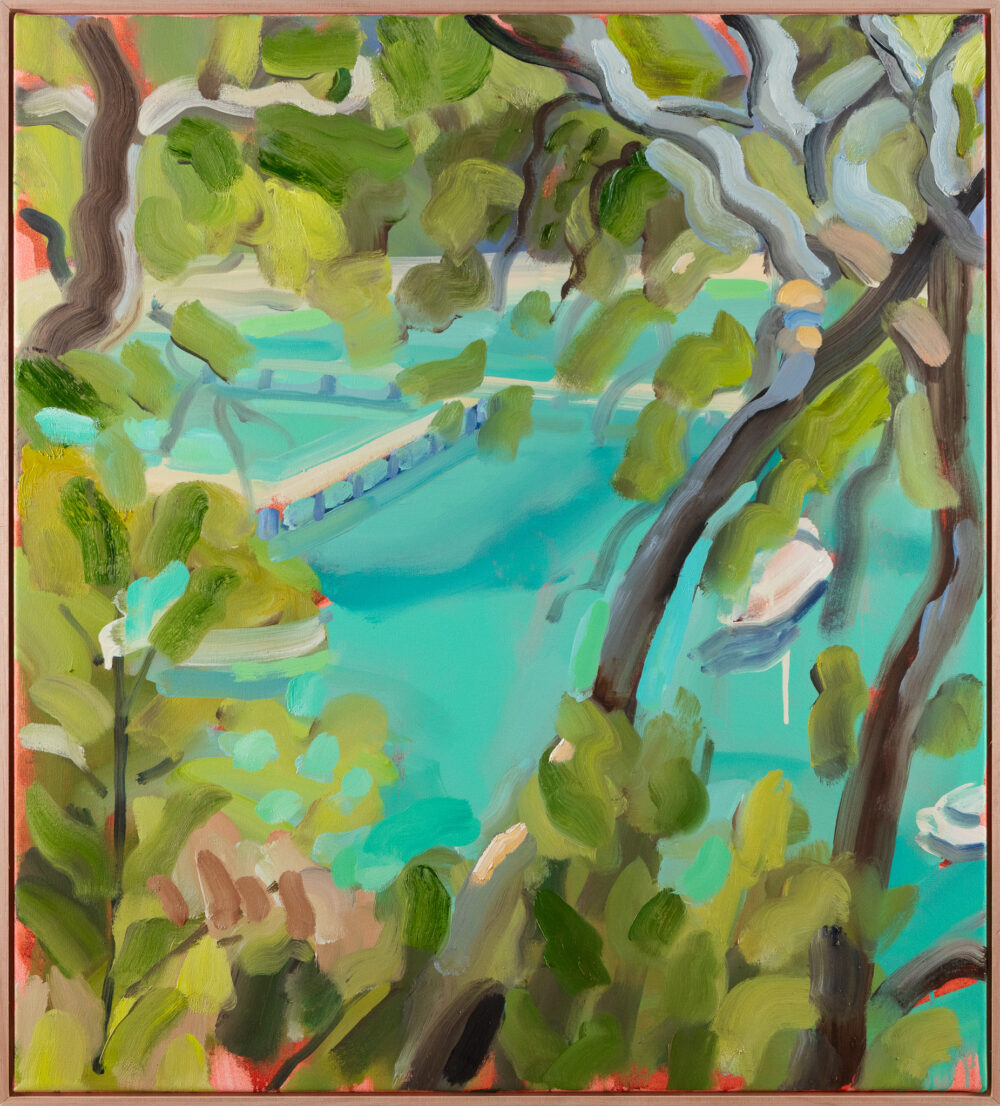

Melanie Waugh

Balmoral, 2025

85 x 75 cm

Melanie Waugh

Clovelly, 2025

85 x 75 cm

$2,800

Melanie Waugh

Clifton Gardens, 2025

105 x 95 cm

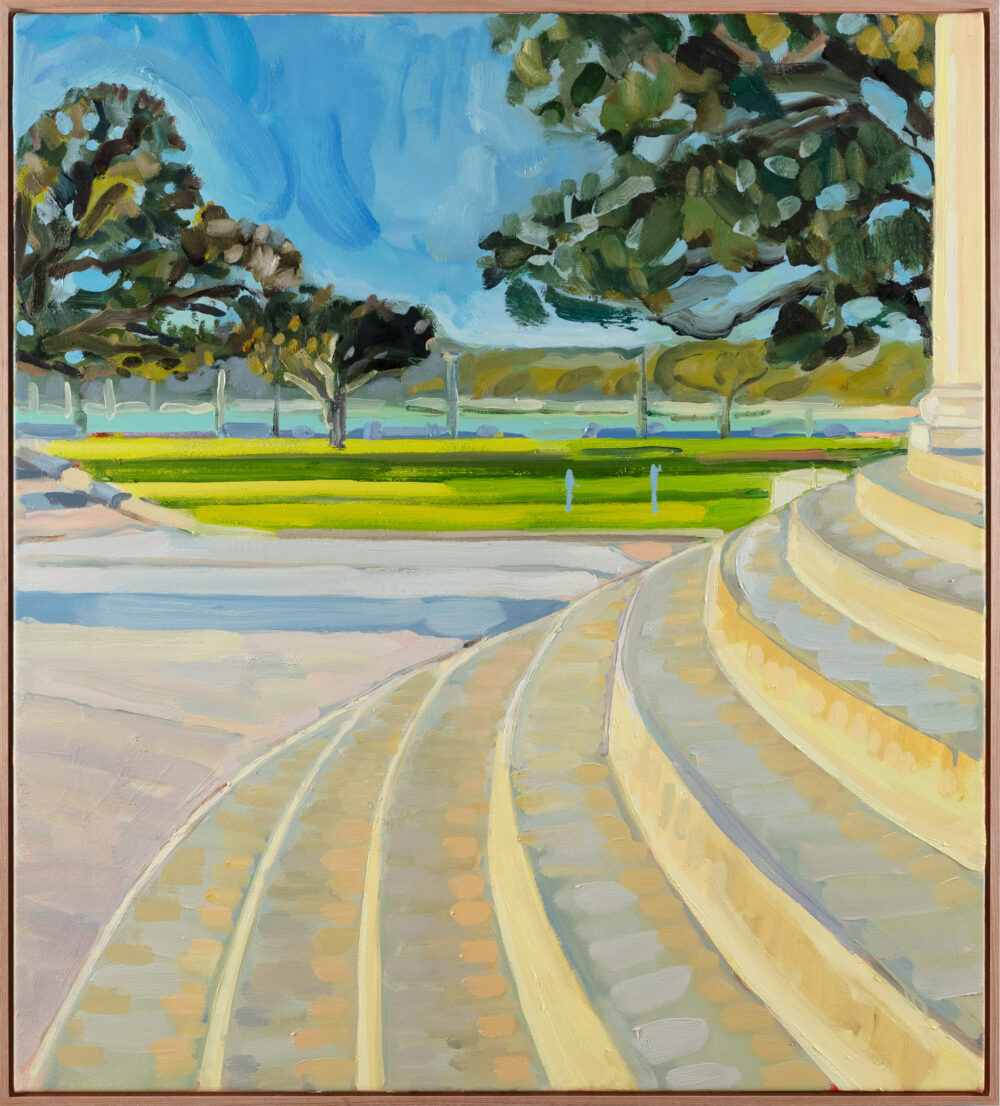

Melanie Waugh

Rotunda at Balmoral, 2025

105 x 95 cm

$4,900

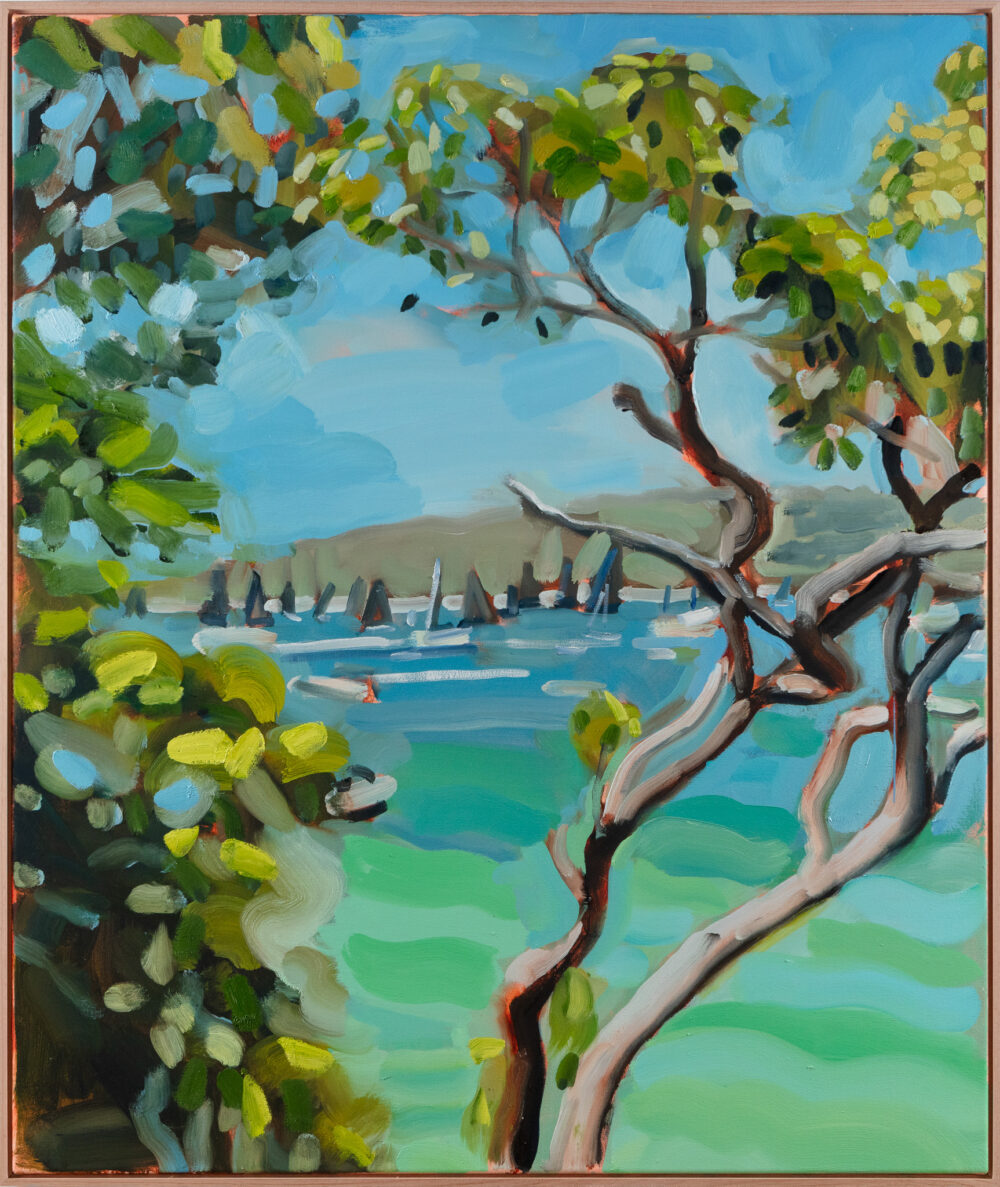

Melanie Waugh

Sydney to Hobart, 2025

125 x 105 cm

SOLD

Melanie Waugh

Robertsons Point Lighthouse, 2025

125 x 105 cm