The Charlotte Project

Words: Michael Sharp. Photography: Ashley Mackevicius, with additional images by Augustin Chauvet.

Charlotte Atkinson was the author of Australia’s first children’s book, which became a bestseller upon its publication in 1841. She was also an accomplished artist and a pioneer for women’s legal rights, successfully fighting a long battle for the right to raise and educate her own children in a case that is still cited in Australian courts today.

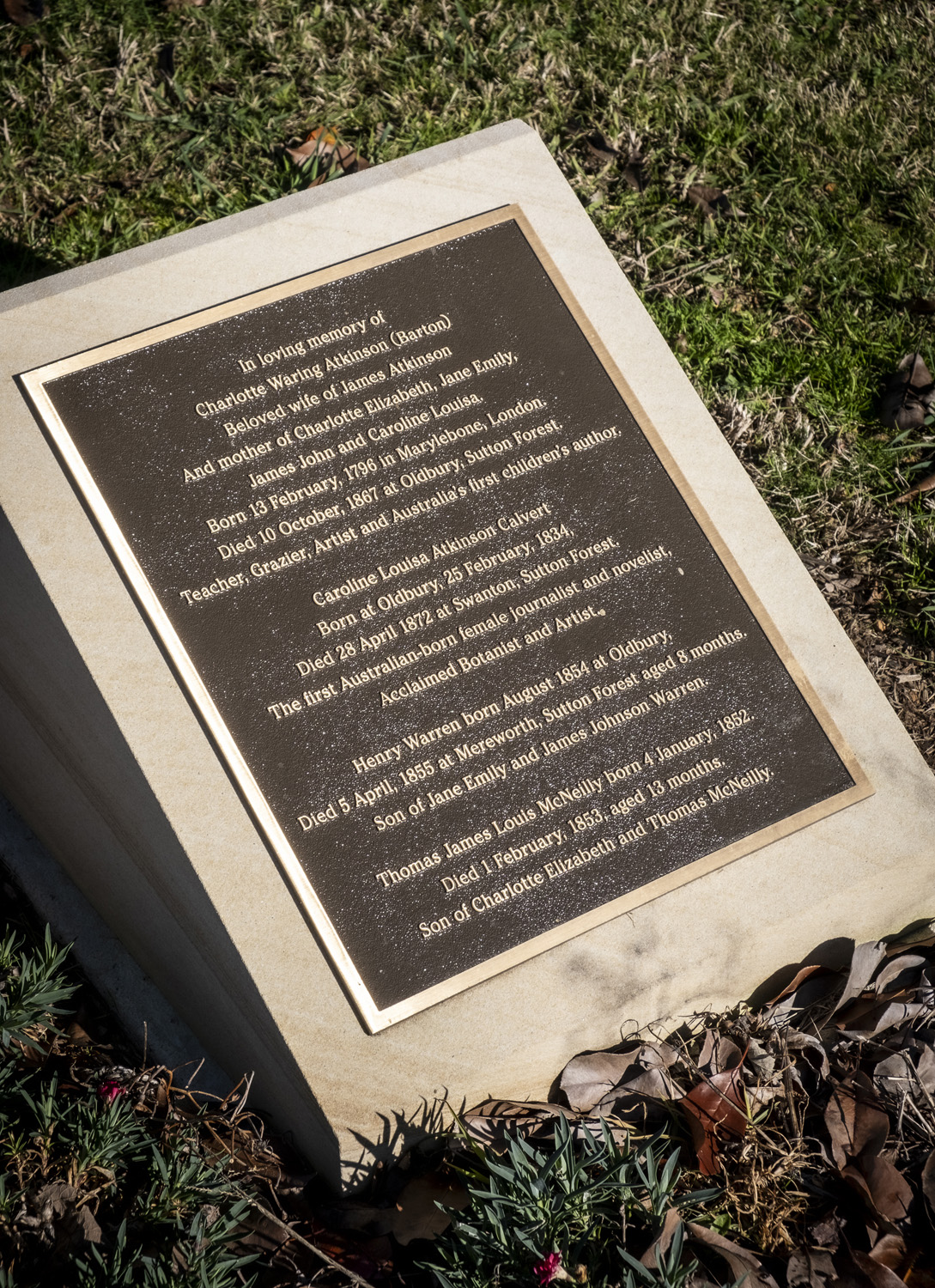

Yet her identity as the author of A Mother’s Offering to Her Children was not discovered until 1981 and until 2022 she lay buried anonymously beneath a gravestone in All Saint’s Anglican Church, Sutton Forest that bore only the name of her first husband.

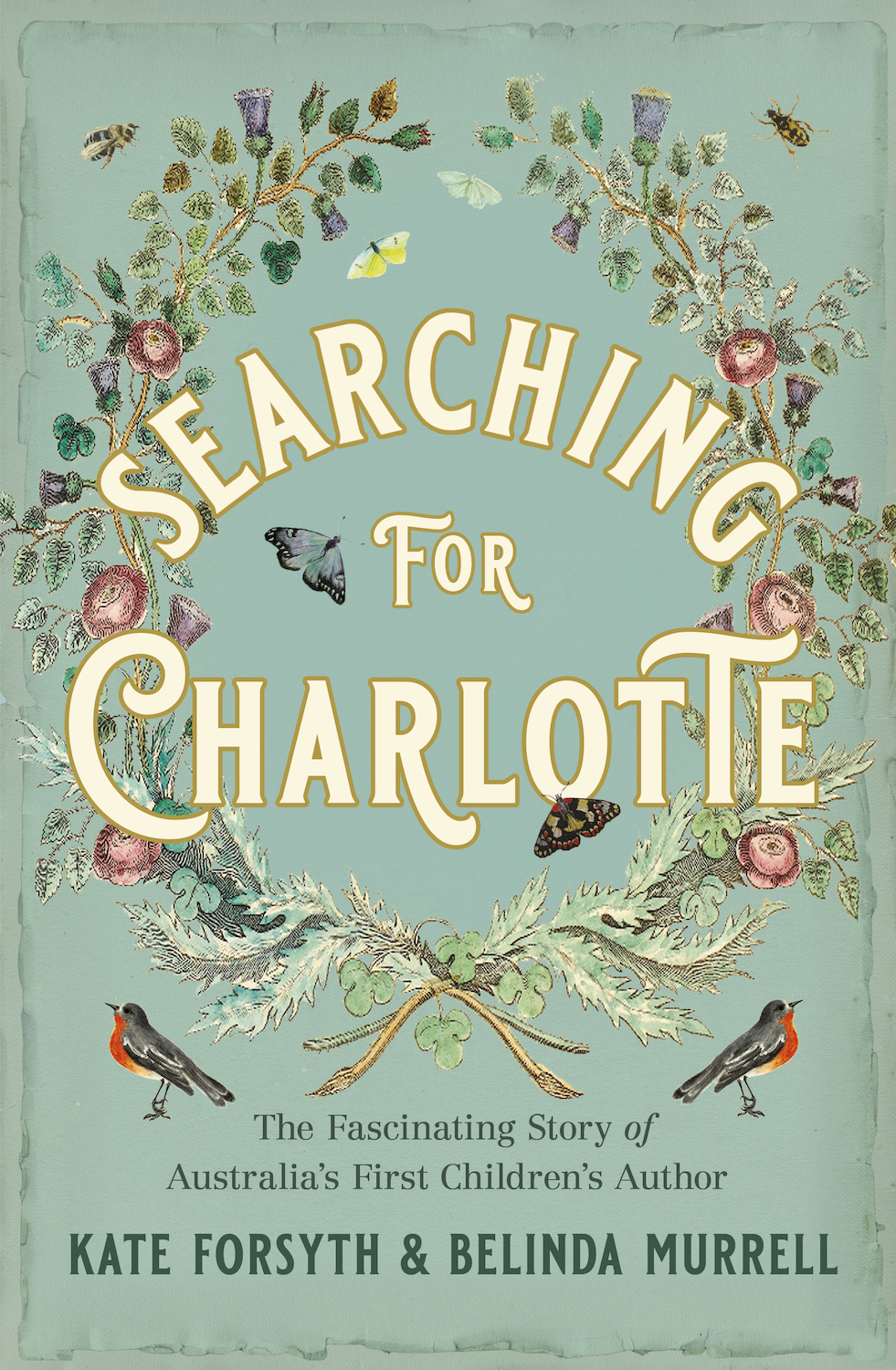

In November 2021 a group of women gathered in The Southern Highlands for a writing retreat titled “True Life Stories”. The retreat leaders were Kate Forsyth and Belinda Murrell, the great-great-great-great-granddaughters of Charlotte Atkinson and the authors of Searching for Charlotte: The Fascinating Story of Australia’s First Children’s Author.

The retreat was the catalyst for the formation of Wingecarribee Women Writers which has joined a global movement that celebrates women’s voices and stories. Their first initiative is The Charlotte Project, a public fundraising appeal to raise $80,000 to erect a bronze statue of Charlotte Atkinson in Berrima’s Market Place Park.

Lynn Watson, Chair of Wingecaribee Women Writers, hadn’t heard of Charlotte before she attended the writers’ retreat just over 18 months ago.

“Charlotte did some mighty things and she was so courageous – her story just appealed to me on so many levels,” Lynn says. “I have five daughters and I’ve always been interested in women having a voice. I have also always been conscious that a lot of women’s stories, and women’s contributions, have been lost or discarded.

“When we visited Charlotte’s grave and saw her name wasn’t on it, we raised some money to get a new plaque. But we realised more should be done to shine a light on her story. We said: let’s go for a bronze statue.

“A year later and we are well on our way to reaching our target. We are overwhelmed at how generous people have been.”

According to Professor Clare Wright, convenor of A Monument of One’s Own, less than 4% of Australia’s statues represent historical female figures. (Mary Poppins is honoured with a statue in nearby Bowral, but she was probably fictional). There are more statues of animals in Australia than of real women.

The patron of Wingecarribee Women Writers is Paula McLean, a philanthropist and former Deputy Chair of The Stella Prize, a major literary award celebrating Australian women’s writing.

“We have a history of failing to recognise the achievements of women and we need to redress this,” Paula says. “The Charlotte Project is very much aligned to the work that I did as Deputy Chair of The Stella Prize. Both of these projects are to celebrate the voices, the stories of women. Public monuments are a very important part of recognising the achievements of people all over the country and we need to recognise the achievements of Charlotte Atkinson. A statue of her will be a wonderful gift to The Southern Highlands community.”

Bowral-based sculptor Julie Haseler Reily volunteered her time to design and make the sculpture. Julie graduated from the National Institute of Dramatic Art, has a Diploma of Visual Arts from TAFE Queensland and has studied at the National Art School, the Ceramics Centre at TAFE Hornsby, and Gaya Ceramics in Ubud, Indonesia.

“This is a great honour for me,” Julie says. “I wanted to breathe life into Charlotte’s story, because she was such an extraordinary woman. A theme in some of my work is “the heroic feminine” and I was intrigued with Charlotte the woman and Charlotte the heroic mother figure. I feel I now know Charlotte very well, having spent so many private hours alone in my studio with her.

“I hope she will be an ornament for Georgian Berrima and a portal to history, providing a fuller understanding of that time and place along with her personal story of courage, resilience, daring and triumph against the odds.”

So who was Charlotte Atkinson?

She was born Charlotte Waring in London in 1796 and emigrated to Australia aboard the Cumberland in 1826 after being employed as a governess by Maria and Hannibal Macarthur. On the voyage she met James Atkinson, an author and agriculturist who was returning to his Australian properties after writing An Account of the State of Agriculture & Grazing in New South Wales.

Charlotte and James were married a year later and settled at Oldbury in Sutton Forest, a property named after James’ father’s estate in Kent. Charlotte and James had four children between 1828 and 1834 and they were a very happy and formidable couple in Berrima District. But then James died suddenly in 1834, aged just 39, after “a painful and lingering illness”.

The Australian Dictionary of Biography notes that James’ death “left his widow to manage a large holding, run far-flung outstations, control convict labour in a district beset by bushranging gangs and care for her children”.

On 3 March 1836 Charlotte married George Barton, who was the superintendent at Oldbury. The marriage changed her legal position from being custodian of Oldbury to being merely the lessor’s wife. Barton proved to be a drunkard, violent and mentally disturbed and in 1839 Charlotte left him and took her children to an outstation at Budgong, south-west of Kangaroo Valley. A year later she moved to Sydney and applied for legal protection from Barton. Atkinson v Barton became a long-running legal battle that challenged the patriarchy and made her a pioneer of women’s rights in Australia.

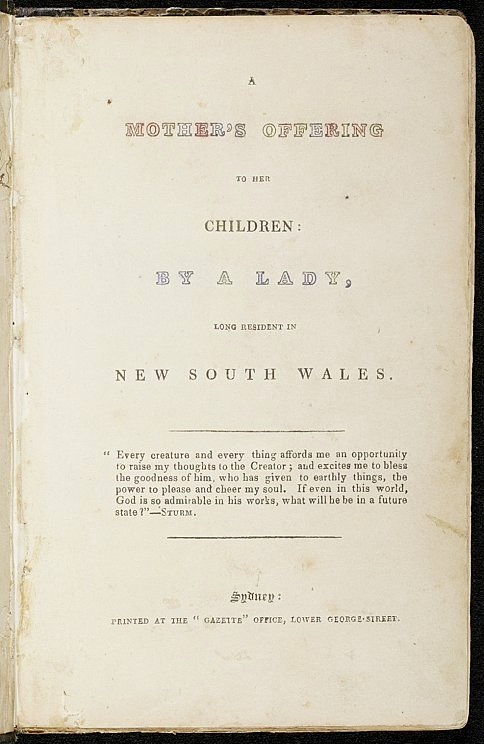

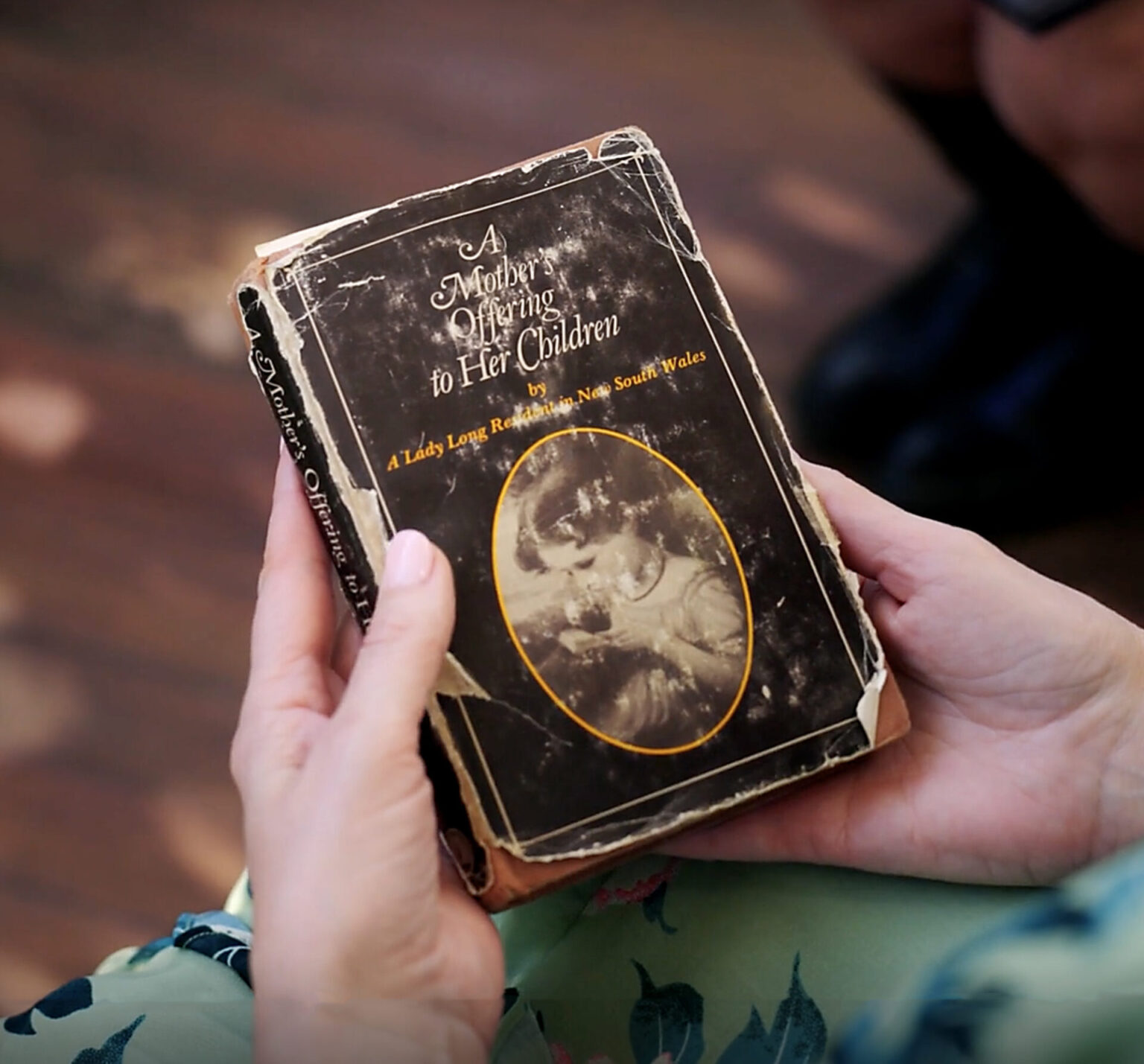

Charlotte was now not receiving any money from the Atkinson estate, so in 1841 she wrote A Mother’s Offering to Her Children, which became the first children’s book to be published in Australia. The author was “A Lady Long Resident in New South Wales” and it was written as a collection of instructional stories from a mother to her four children. It featured Australian flora and fauna, Australian landscapes and the lives of First Nations people – and this was the key to its immediate and widespread popularity. A first edition sold recently for $70,000.

Charlotte returned to Oldbury in 1846 and died there in 1867. Her determination to educate her children was most notably rewarded by the achievements of her daughter Louisa – the first Australian-born female novelist, journalist and botanist.

The sculpture of Charlotte is currently being cast at the renowned Crawford’s Casting foundry in Sydney and Wingecaribee Women Writers hope it will be unveiled before the end of the 2023 calendar year.

Charlotte will be seen reclining on the ground, holding out a copy of her famous book to four sandstone block seats that both represent her four children and allow visitors to engage with the sculpture.

“Thousands of school children stop off at Berrima’s Market Place Park each year for a break on their journey,” Lynn Watson notes. “Besides having a run around and a swing, they will see a statue of this colonial woman in this colonial village. We hope that teachers will explain who she is and it might spark interest in Charlotte and the significant contribution that so many women have made to our history.”

For more information, and to make a donation to The Charlotte Project, visit www.womenwriters.org

Michael Sharp

Michael is the Gallery Manager at Michael Reid Southern Highlands. He has previously worked as a lawyer, journalist and senior practitioner in Australian corporate affairs.

Ashley Mackevicius

Ashley discovered photography at the age of 15, which proved to be a lifeline for the academically challenged son of Lithuanian migrants. He has had a long and successful career and lives in The Southern Highlands.

- xxi Pecora Dairy June 2024

- xxx In Conversation: Evan Shipard March 2026

- XXIX David King December 2025

- XXVIII Nicola Woodcock August 2025

- xxvii Marlie Draught Horse Stud May 2025

- xxvi India Mark February 2025

- xxv Mussett Holdings December 2024

- xxiv Louise Frith October 2024

- xxiii Dirty Jane August 2024

- xxii Melanie Waugh July 2024

- xx Emily Gordon May 2024

- xix Steve Hogwood March 2024

- xviii Julz Beresford February 2024

- xvii Snake Creek Cattle Company November 2023

- xvi Ben Waters September 2023

- xv The Reid Brothers August 2023

- xiv Elizabeth Beaumont July 2023

- xiii The Charlotte Project June 2023

- xii Buddhism in Bundanoon May 2023

- xi Honey Thief April 2023

- x David Ball February 2023

- ix Kate Vella January 2023

- viii The Truffle Couple December 2022

- vii Wombat Man November 2022

- vi Storybook Alpacas September 2022

- v Tamara Dean August 2022

- iv John Sharp July 2022

- iii Amanda Mackevicius June 2022

- ii Denise Faulkner May 2022

- i Joadja Distillery March 2022