David Ball

Words: Michael Sharp.

Photography: Ashley Mackevicius.

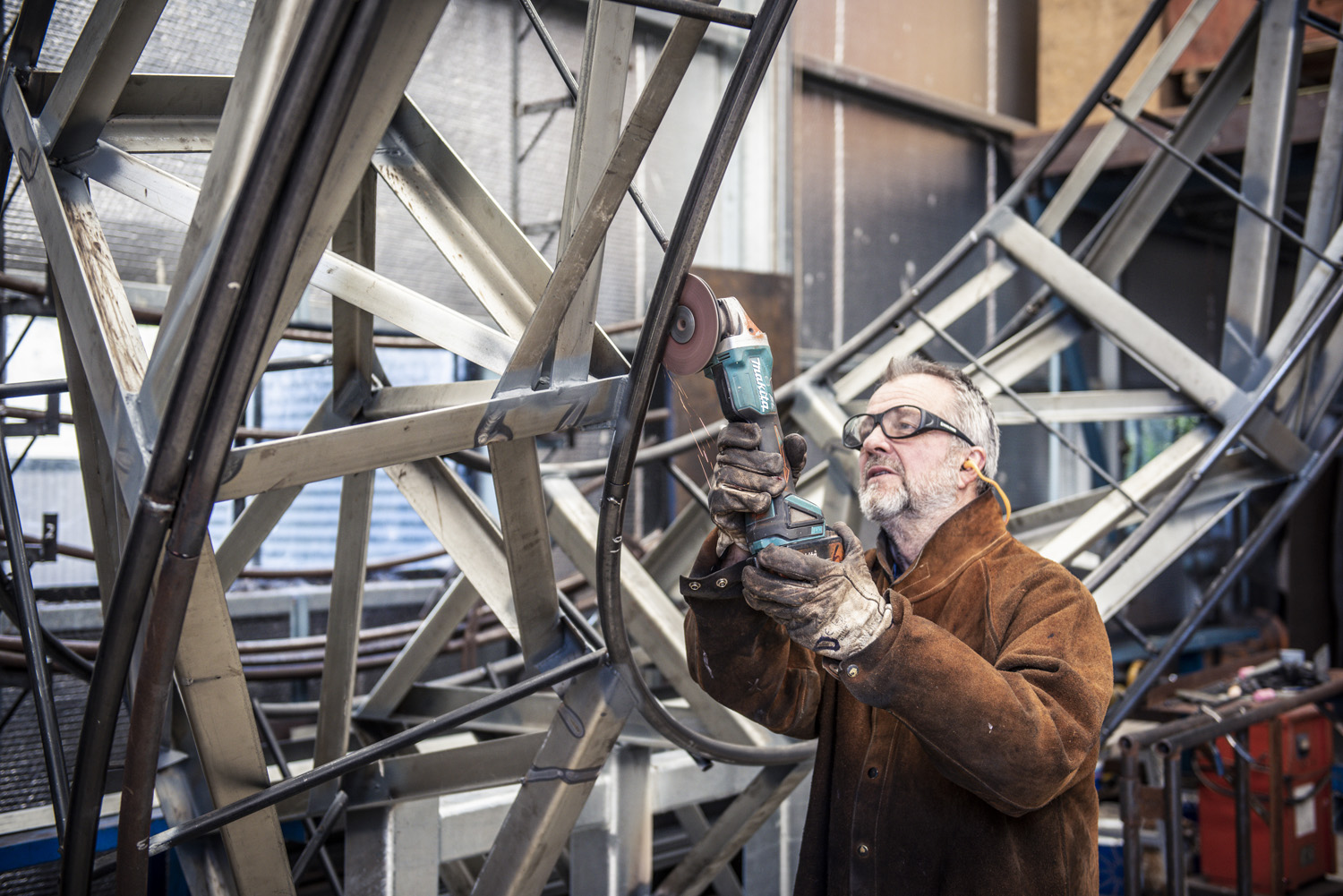

David Ball’s vast steel sculptures are often described as having a quiet energy – and this description also fits the man behind the monumental works.

“I’ve never been a real people person,” he says as we drink coffee on an old bench outside the large workshop shed on his 22 hectares property in Wildes Meadow. “It’s not that I dislike humans, it’s just that I find nature more inspiring. There are a lot of great human stories, but it’s just not my bag. The human story has been told over and over yet nature is endlessly inspiring, from the molecular to the cosmic.”

This love of nature has been with him all his life.

“I had a perfect childhood,” he says calmly. “I was the last of three children, and a late comer, so my parents had done all their controlling with the first two and when I came along they were just over it. I was allowed to go free.

c

Ball went to the local primary school and then North Sydney Boys High School but says he wasn’t a natural student. “I really fudged my way through school,” he laughs.

When it is pointed out that North Sydney Boys is a selective school, he responds: “I was very good at fudging! I was probably dyslexic, though that was never diagnosed formally. My reading and writing skills were average, but my abstract thinking skills and my ability to visualise things were above average. Maybe it was just a counter, like a blind man having good hearing. And it was a way for me to feel ok about myself.”

While he was good at art, Ball had an aversion to institutions from an early age – and this included art school.

“I just enjoyed doing my own thing. I’m glad I didn’t go to art school because my spirit and my mind are uncontaminated – although they are contaminated by other things! But I wasn’t told how to do it, I wasn’t institutionalised.”

As soon as he “broke the shackles” of high school, he rode a bicycle to Tasmania – and then around Tasmania. He did a lot of cycling and bushwalking in his post-school years, including in Europe and The Himalayas, travelling with a tent and rejoicing at being out in the world and under the stars.

In his late teens he began training with a stonemason and horticulturist.

“I loved it, because I was in touch with nature, and I was quite good at it. But it became too restrictive and I soon walked away.”

At the age of 22, he cycled to The Flinders Ranges with his then girlfriend. The young couple rode into the town of Melrose and saw a run-down blacksmith’s shop that had been built in 1865 and was made of stone, wattle and daub – or pug and pine as they call it in South Australia.

“We’d been looking to set something up and it was just what we could afford. So we went ahead and bought it. A week later, some other artists happened to move to Melrose from Melbourne and we formed this fantastic friendship and lived this wonderful young, free life.”

David’s newly acquired stonemasonry skills proved valuable as they spent the next 12 years restoring the blacksmith’s shop so that it was operational again. They added a licensed restaurant and Bluey Blundstone’s Blacksmith Shop won national heritage and tourism awards. Ball learned a huge amount through the restoration, including “that you can make something from nothing and that if you do something well enough you can do it anywhere and it will work”.

However, the project was all-consuming and took its toll.

“We had created a monster,” Ball reflects. “The business took hold of us and destroyed us. We ended up leaving fairly broken from giving so much and not replenishing ourselves.”

Ball returned to New South Wales and moved to live near his brothers in The Southern Highlands.

“I found a cheap place to live and scratched together a workshop. I dug some logs out of the bush, stuck them in the ground and put some tin on top. I managed to find myself a forge, an anvil and a welder – and I started making sculptural furniture with wood and steel.”

In 1997 he had a solo show at Sturt Gallery in Mittagong.

“I didn’t sell much but it was well received and I began to get work with architects. I made ‘left of field’ staircases and doors and had a steady stream of work. Gradually, I moved away from function and more into form. I threw the spirit level away and my tape measure became less important. It was all about the eye and form and line. Eventually, I stopped working for architects and became a full-time sculptor.”

In 2012, Ball was invited to participate in the inaugural Sculpture-on-High exhibition held at Hillview, a property in Sutton Forest that had been a vice-regal retreat for the Governors of New South Wales from 1882 until 1958. Significantly, he decided to substantially increase the scale of his work – and he was delighted to be awarded first prize. Hillview became a biennial sculpture exhibition and Ball became increasingly involved, including curation.

“My career grew with Hillview. It was an ideal platform for me to put my sculpture in the landscape, which is so important, and for it to be seen.”

He also decided it was time to have another crack at Sculpture By The Sea.

“I had submitted works to Sculpture By The Sea several times previously and been rejected – and rightly so,” he says frankly.

But in 2017 his large circular work titled Orb was not only accepted, it won the competition.

“And then my profile went through the roof,” he says, seemingly still surprised by his success. “Sculpture By The Sea has been critical to my career because it puts sculpture in the fore of people’s minds as something that reflects our culture, us.”

Ball has consistently won prizes in his sculpting career since 1999, has received numerous public commissions (including the Wollondilly River Walkway near Goulburn and Sculpture Down the Lachlan between Forbes and Condoblin) and is part of private sculpture collections across south-eastern Australia.

“This brings me great joy, making and seeing my work in the landscape,” he says.

Ball was in his late 50s when he won Sculpture By The Sea, so he is no overnight success.

“It’s a long journey and you must have a deep passion. You also have to have a thick skin. You must learn to wear rejection and accept that rejection pushes you further down the track. Your desire has to be deep enough for you to cope with that, to keep your eye on the goal. You need a deep well to tap into, especially in difficult times.”

Today, just as when he was a boy, Ball’s inspiration comes from his love of the bush and nature.

“When I was growing up, if you couldn’t articulate your thoughts people thought you were a bit stupid. My mind has always been very articulate in abstraction and the visual – textures and lines. The visual arts were a natural world for me. That’s what art and sculpture is to me, it’s a visual language. A language that I understand. Music is the same. I see no difference between music and sculpture. I see my sculptures as bold, simple melodies – although sometimes they are more ragged works of atonal abstraction. But the prime motivation for me is that it doesn’t involve words. The fact I can articulate my thoughts through this visual language is key to me.”

Ball’s sculptures are physically demanding to construct and, while he works with a couple of assistants, he knows he is closer to the end of his career than its beginning.

“But I still have plenty of ideas and I’ll keep going until I can’t,” he says with a glint in his eye. “All these shapes are floating around in my brain and, if I decide they are good enough, the only way to get rid of them is to manifest them into steel.”

For more information visit www.davidball.com.au

Michael Sharp

Michael is the Gallery Manager at Michael Reid Southern Highlands. He has previously worked as a lawyer, journalist and senior practitioner in Australian corporate affairs.

Ashley Mackevicius

Ashley discovered photography at the age of 15, which proved to be a lifeline for the academically challenged son of Lithuanian migrants. He has had a long and successful career and lives in The Southern Highlands.

- xxi Pecora Dairy June 2024

- xxx In Conversation: Evan Shipard March 2026

- XXIX David King December 2025

- XXVIII Nicola Woodcock August 2025

- xxvii Marlie Draught Horse Stud May 2025

- xxvi India Mark February 2025

- xxv Mussett Holdings December 2024

- xxiv Louise Frith October 2024

- xxiii Dirty Jane August 2024

- xxii Melanie Waugh July 2024

- xx Emily Gordon May 2024

- xix Steve Hogwood March 2024

- xviii Julz Beresford February 2024

- xvii Snake Creek Cattle Company November 2023

- xvi Ben Waters September 2023

- xv The Reid Brothers August 2023

- xiv Elizabeth Beaumont July 2023

- xiii The Charlotte Project June 2023

- xii Buddhism in Bundanoon May 2023

- xi Honey Thief April 2023

- x David Ball February 2023

- ix Kate Vella January 2023

- viii The Truffle Couple December 2022

- vii Wombat Man November 2022

- vi Storybook Alpacas September 2022

- v Tamara Dean August 2022

- iv John Sharp July 2022

- iii Amanda Mackevicius June 2022

- ii Denise Faulkner May 2022

- i Joadja Distillery March 2022