David King

Photography: Ashley Mackevicius

David King’s studio is crowded but not chaotic: a workbench dense with rollers, chisels, scourers, glue guns; canvases leaning against the walls like half-formed thoughts; and, everywhere, the smell of wet oil paint lifting off the surface in faint sweet vapours. In one corner, a nearly finished landscape — all scraped-back sky and telegraph poles — waits for its next intervention. In another, a pile of rags has been pressed into service as an impromptu palette.

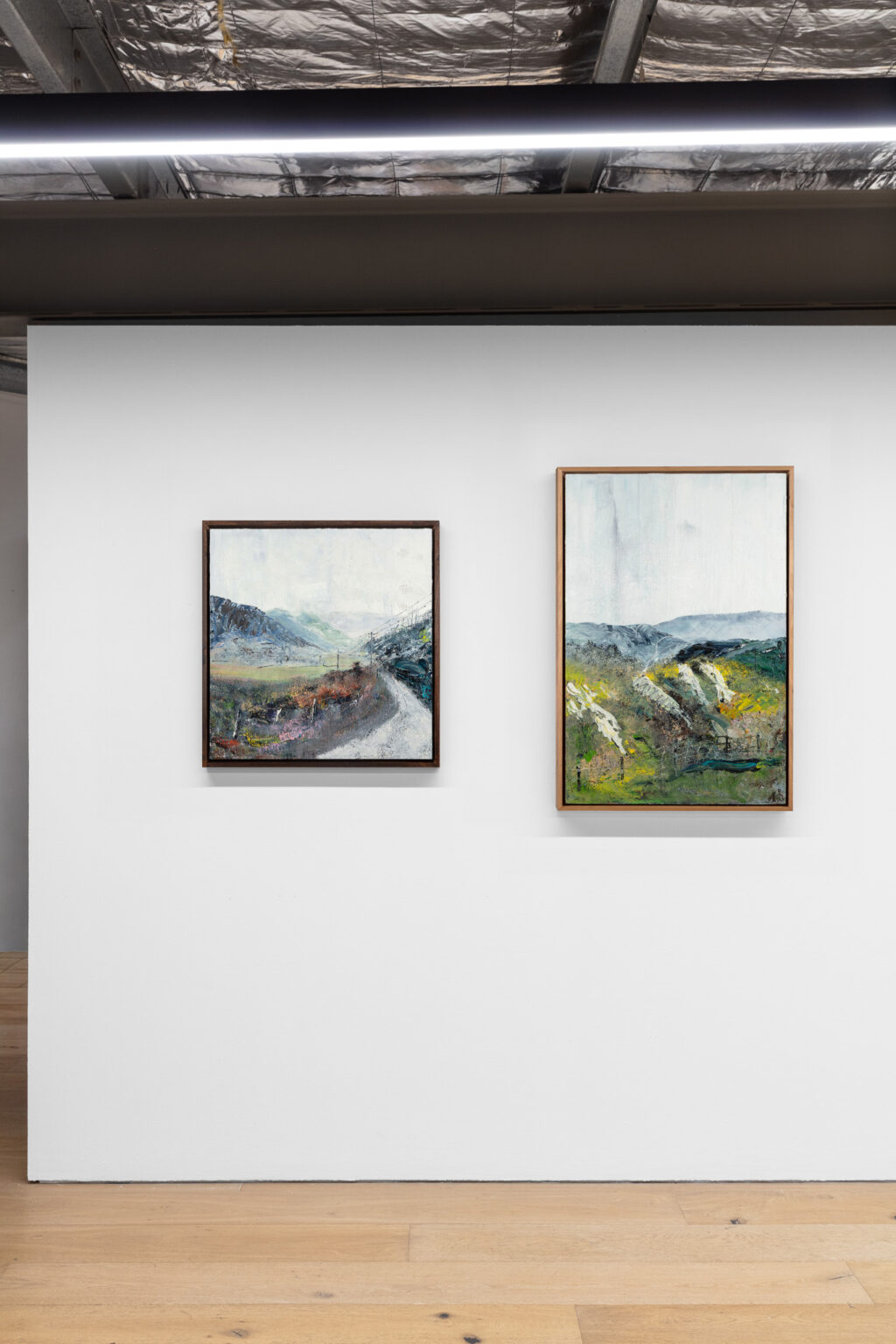

The scenes King has painted for his debut solo collection, Lines on the Landscape — opening soon in the Top Floor Gallery — travel widely: the Illawarra escarpment, the Central Tablelands, the edges of Goulburn, Orford’s pale fields, and the misted greens of Ireland. Yet his subject is not geography. “I see the same things everywhere,” he says. “Ireland, Tasmania, the Tablelands — fences, gates, telegraph poles. They join all these places.”

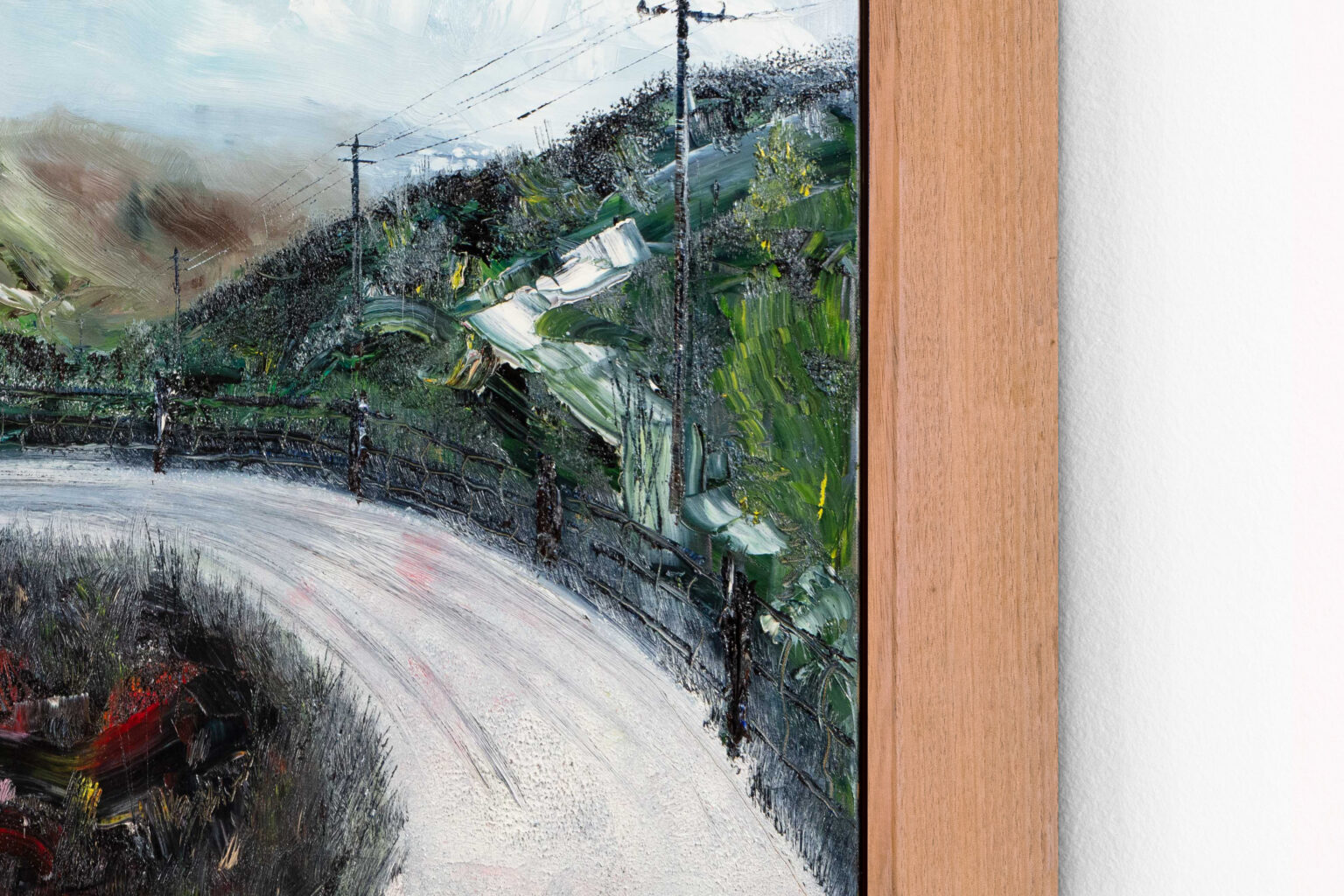

These structures matter in the most practical sense: they give the painting a load-bearing point. A telegraph pole becomes a vertical anchor for the composition; a fence line offers direction; a curve of road holds the scene together long enough for him to pull it apart again. They are the scaffolding that allows the surface to behave the way he needs it to.

The artist’s method is deeply physical. “I use anything — a scourer, a piece of card, a chisel,” he says. Brushes have largely disappeared from his practice. His preferred tool is a sponge, which he presses into the paint and drags in long, shearing movements that leave ridges, ruts, and sudden clearings. Working on board gives him licence to scrape back without hesitation, taking out whole passages in the knowledge that the surface won’t give way.

This surface — unruly and layered— is what some have called his “punk impasto.” King deflects the label, but he understands the impulse behind it. “It can be messy,” he says. “But you get these moments of magic unexpectedly.”

Those “moments” are what he has learned to protect. Paul Ryan, his neighbour-turned-mentor, once told him, “When the moment of magic happens, you’ll know it — and leave it alone.” King repeats the line like a rule of life. The discipline is not to improve but to stop. If a gesture lands cleanly — a scraped horizon, a shock of bright ochre, a single pass of the sponge that resolves a hillside — he recognises it instantly and refuses to touch it again.

This instinctive alertness comes, in part, from music. Before he painted, King trained as a classical guitarist, then an opera singer. The intensity and exposure of performing still visibly inhabit him. “On stage you must overcome fear and sing without hesitation,” he says. “When you let go, everything works.” That state — the moment when instinct overrides technique — is what he chases in painting.

King’s relationship to landscape is also shaped by a lifetime of looking, travelling, comparing. He photographs constantly. Back in the studio, he zooms in on each image, scanning for the thing that “catches” — not beauty, but some stray structural or emotional charge that suggests a painting might be possible. “You’re not 100% sure until you start,” he says. And once he starts, the photograph is discarded. The painting becomes an argument with the surface, not a record of the view.

His influences run deep: his late father, -and celebrated Irish artist – Cecil King’s sculptural studio, the smell of clay and cold-cast bronze; Celtic forms; horses; Dublin’s Bull Wall and the enormous Virgin Mary statue his father made for the port. These early experiences taught him that art is a long haul — a discipline, not a mood. They also taught him to understand his materials intimately: how they behave, how they resist, how they can be pushed until they break and still hold together.

This new body of work reflects all of that: the music, the mentorship, and the sculptural inheritance. The landscapes feel more open than before — a shift in temperature, a softening at the edges that King recognises as Ireland resurfacing in him. He’s learned to use strong colour more sparingly, letting quieter passages carry the emotional weight.

When he speaks about his practice, King doesn’t describe a direction so much as a willingness. “I don’t fear the canvas,” he says. “Mistakes aren’t mistakes — they’re another bend in the road.”

It’s an apt description of the work itself: landscapes that bend and swerve, dismantle themselves, start over, and emerge stronger.

In the end, what King is painting is less the landscape in front of him than the force he brings to meet it. The terrain changes — Illawarra, Orford, Ireland — but the energy is constant. The surface stays alive. And in that agitation, that insistence on keeping the paint moving until it reveals something true, the work finds its centre.

Ashley Mackevicius

Ashley discovered photography at the age of 15, which proved to be a lifeline for the academically challenged son of Lithuanian migrants. He has had a long and successful career and lives in The Southern Highlands.

- xxi Pecora Dairy June 2024

- XXIX David King December 2025

- XXVIII Nicola Woodcock August 2025

- xxvii Marlie Draught Horse Stud May 2025

- xxvi India Mark February 2025

- xxv Mussett Holdings December 2024

- xxiv Louise Frith October 2024

- xxiii Dirty Jane August 2024

- xxii Melanie Waugh July 2024

- xx Emily Gordon May 2024

- xix Steve Hogwood March 2024

- xviii Julz Beresford February 2024

- xvii Snake Creek Cattle Company November 2023

- xvi Ben Waters September 2023

- xv The Reid Brothers August 2023

- xiv Elizabeth Beaumont July 2023

- xiii The Charlotte Project June 2023

- xii Buddhism in Bundanoon May 2023

- xi Honey Thief April 2023

- x David Ball February 2023

- ix Kate Vella January 2023

- viii The Truffle Couple December 2022

- vii Wombat Man November 2022

- vi Storybook Alpacas September 2022

- v Tamara Dean August 2022

- iv John Sharp July 2022

- iii Amanda Mackevicius June 2022

- ii Denise Faulkner May 2022

- i Joadja Distillery March 2022